Scientists have developed what they say is the world’s first “vagina-on-a-chip,” which uses living cells and bacteria to mimic the microbial environment of the human vagina. It could help to test drugs against bacterial vaginosis (BV), a common microbial imbalance that makes millions of people more susceptible to sexually transmitted diseases and puts them at risk of preterm delivery when pregnant.

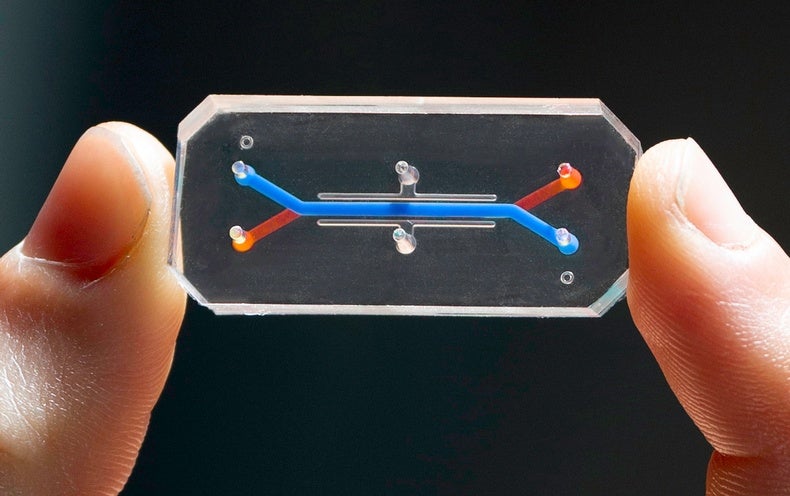

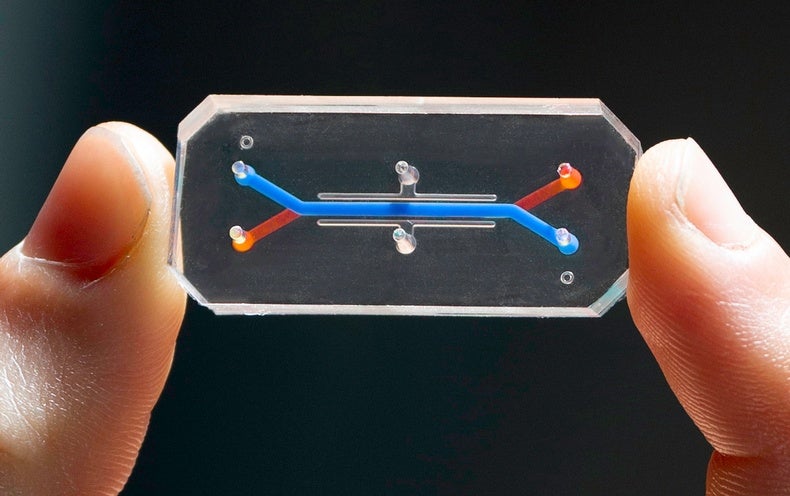

Vaginal health is difficult to study in a laboratory setting partly because laboratory animals have “totally different microbiomes” than humans do, says Don Ingber, a bioengineer at Harvard University’s Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering. To address this, he and his colleagues created their unique chip, described in Microbiome: an inch-long, rectangular polymer case containing live human vaginal tissue from a donor and a flow of estrogen-carrying material to simulate vaginal mucus.

So-called organs-on-a-chip mimic real bodily function, making it easier to study diseases and test drugs. Previous examples include models of the lungs and the intestines. In this case, the tissue acts like that of a real vagina in some important ways. It even responds to changes in estrogen by adjusting the expression of certain genes. And it can grow a humanlike microbiome dominated by “good” or “bad” bacteria.

For example, a lot of the time, “Lactobacilli bacteria keep your vagina nice and acidic,” says Ruth Mackay of Brunel University London, who was not involved with the new study. “But then Gardnerella come in ... and create this alkaline environment.” That can lead to BV.

Ingber and his colleagues have demonstrated that Lactobacilli growing on the chip’s tissue help to maintain a low pH by producing lactic acid. Conversely, if the researchers introduce Gardnerella, the chip develops a higher pH, cell damage and increased inflammation: classic BV signs. In other words, the chip can show how a healthy—or unhealthy—microbiome affects the vagina.

The next step is personalization. Ingber says his team has already begun to study individuals’ varying microbiomes by loading their personal bacterial communities onto chips using vaginal swabs from donors.

The chip is a real leap forward, says sexual health physician Achyuta Nori of St. George’s, University of London, who was not involved with the study. “It could change how we practice medicine,” he says. Nori says he is particularly excited by the prospect of testing how typical antibiotic treatments against BV affect the different bacterial strains. Currently, “the quality of evidence for most women’s health [issues] is very, very poor,” he says. “This is an opportunity to bring women’s health into the modern times, using modern technology.”

Critics of organ-on-a-chip technology often raise the point that it models organs in isolation from the rest of the body. “It does have its limitations,” Mackay says. For example, many researchers are interested in vaginal microbiome changes that occur during pregnancy because of the link between BV and labor complications. Although the chip’s tissue responds to estrogen, Mackay is not convinced it can fully mimic pregnancy without feedback loops from other organs.

Ingber says that for simulating bigger processes such as pregnancy, researchers “may not need all the other complexity that people assume is important.” Nevertheless, his team is already working on connecting the vagina chip to a cervix chip, which could better represent the larger reproductive system.

Even if some applications will require more development, Mackay is thrilled that the chip is a reality. Beyond being an important technological advance, she says, the interest of someone like Ingber—whom she calls the “godfather” of organ chip technology—may help to normalize research on vaginas. “There shouldn’t be any stigma around it,” she says. “But there is.”

www.scientificamerican.com

www.scientificamerican.com

Vaginal health is difficult to study in a laboratory setting partly because laboratory animals have “totally different microbiomes” than humans do, says Don Ingber, a bioengineer at Harvard University’s Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering. To address this, he and his colleagues created their unique chip, described in Microbiome: an inch-long, rectangular polymer case containing live human vaginal tissue from a donor and a flow of estrogen-carrying material to simulate vaginal mucus.

So-called organs-on-a-chip mimic real bodily function, making it easier to study diseases and test drugs. Previous examples include models of the lungs and the intestines. In this case, the tissue acts like that of a real vagina in some important ways. It even responds to changes in estrogen by adjusting the expression of certain genes. And it can grow a humanlike microbiome dominated by “good” or “bad” bacteria.

For example, a lot of the time, “Lactobacilli bacteria keep your vagina nice and acidic,” says Ruth Mackay of Brunel University London, who was not involved with the new study. “But then Gardnerella come in ... and create this alkaline environment.” That can lead to BV.

Ingber and his colleagues have demonstrated that Lactobacilli growing on the chip’s tissue help to maintain a low pH by producing lactic acid. Conversely, if the researchers introduce Gardnerella, the chip develops a higher pH, cell damage and increased inflammation: classic BV signs. In other words, the chip can show how a healthy—or unhealthy—microbiome affects the vagina.

The next step is personalization. Ingber says his team has already begun to study individuals’ varying microbiomes by loading their personal bacterial communities onto chips using vaginal swabs from donors.

The chip is a real leap forward, says sexual health physician Achyuta Nori of St. George’s, University of London, who was not involved with the study. “It could change how we practice medicine,” he says. Nori says he is particularly excited by the prospect of testing how typical antibiotic treatments against BV affect the different bacterial strains. Currently, “the quality of evidence for most women’s health [issues] is very, very poor,” he says. “This is an opportunity to bring women’s health into the modern times, using modern technology.”

Critics of organ-on-a-chip technology often raise the point that it models organs in isolation from the rest of the body. “It does have its limitations,” Mackay says. For example, many researchers are interested in vaginal microbiome changes that occur during pregnancy because of the link between BV and labor complications. Although the chip’s tissue responds to estrogen, Mackay is not convinced it can fully mimic pregnancy without feedback loops from other organs.

Ingber says that for simulating bigger processes such as pregnancy, researchers “may not need all the other complexity that people assume is important.” Nevertheless, his team is already working on connecting the vagina chip to a cervix chip, which could better represent the larger reproductive system.

Even if some applications will require more development, Mackay is thrilled that the chip is a reality. Beyond being an important technological advance, she says, the interest of someone like Ingber—whom she calls the “godfather” of organ chip technology—may help to normalize research on vaginas. “There shouldn’t be any stigma around it,” she says. “But there is.”

First ‘Vagina-on-a-Chip’ Will Help Researchers Test Drugs

A new chip re-creates the human vagina’s unique microbiome