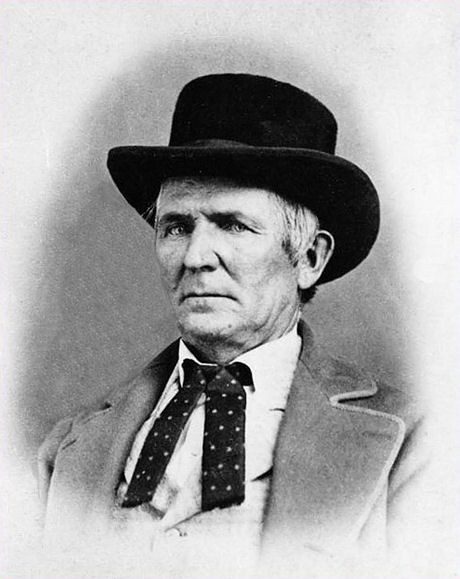

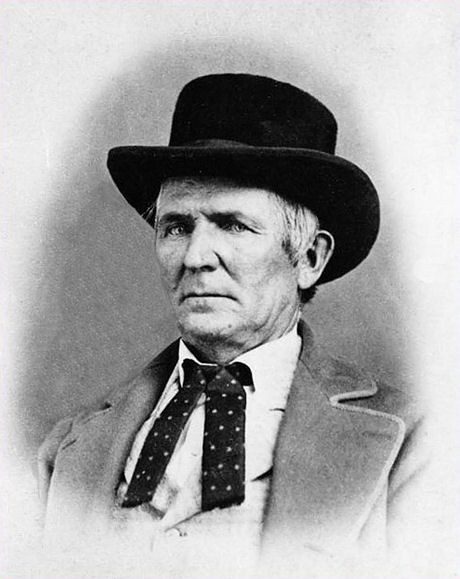

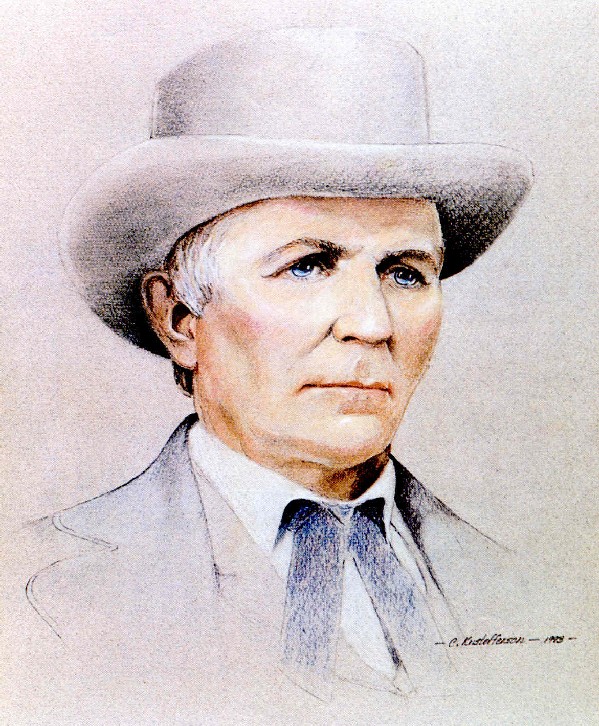

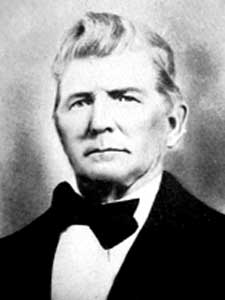

John Doyle Lee

"The Mountain Meadows Massacre"

Classification: Murderer

Characteristics: The most controversial figure in Mormon history

Number of victims: 120 +/-

Date of murders: September 1857

Date of arrest: 1874

Date of birth: September 12, 1812

Victims profile: Men, women, and children (emigrant group known as the Fancher party)

Method of murder: Shooting - Stabbing with knife

Location: Utah, USA

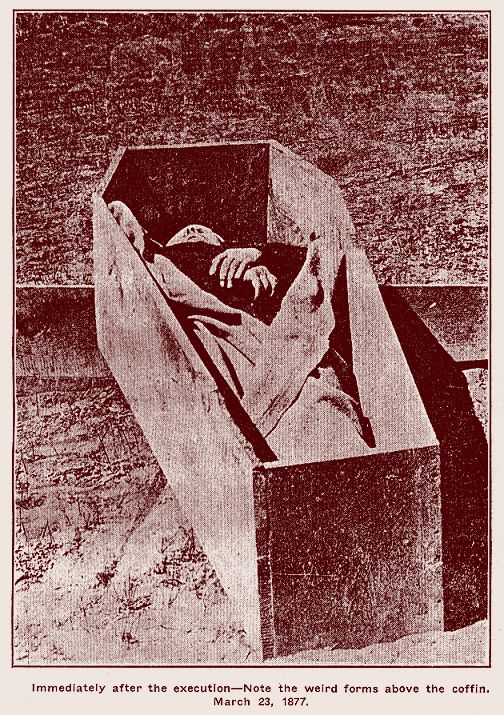

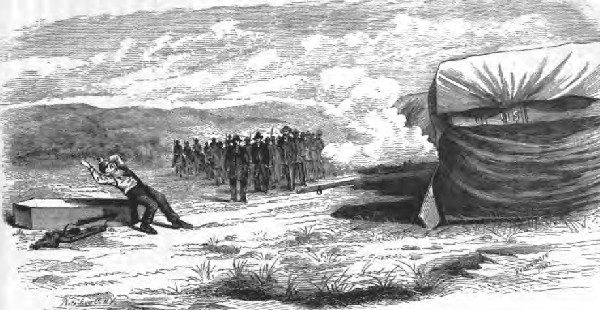

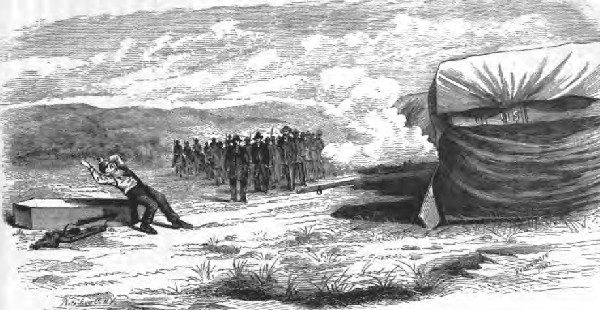

Status: Executed by firing squad on March 23, 1877 on the site of the 1857 massacre

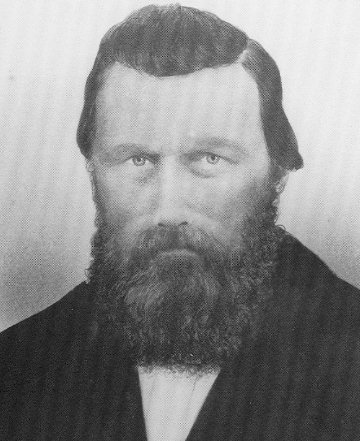

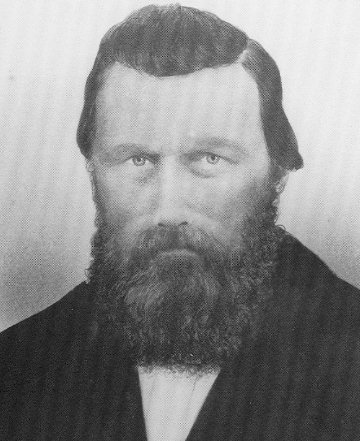

John Doyle Lee (September 12, 1812 - March 23, 1877) was a prominent, early Latter-day Saint (LDS or Mormon) and came to be known as the central figure in the Mountain Meadows Massacre.

Early Mormon leader

Lee was born in Illinois Territory, and joined The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) in 1838.

In 1839 Lee served a Mormon mission with his boyhood friend, Levi Stewart. Together they preached in Illinois, Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessee. It is noteworthy that Lee converted and baptized "Wild Bill" Hickman during this mission.

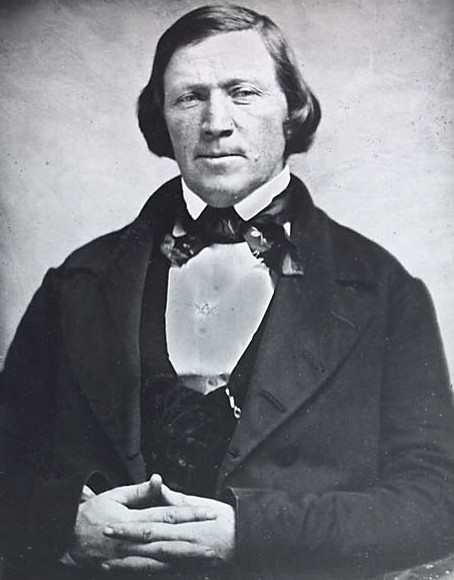

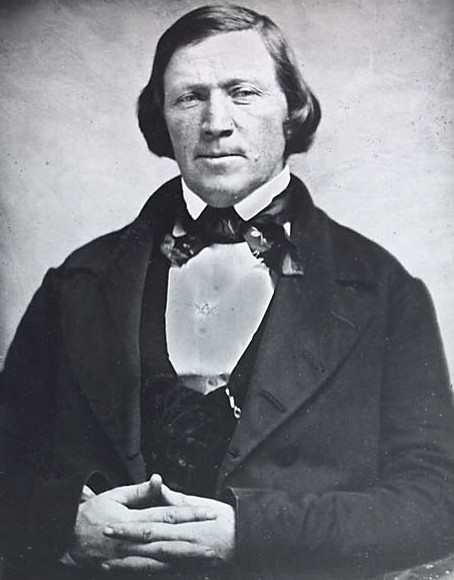

Lee was a friend of Joseph Smith, Jr. founder of the LDS Church. Lee practiced plural marriage and had nineteen wives and sixty-seven children. Lee was allegedly a member of the Danites, although some have argued there is little or no evidence for his involvement in the group. He was an official scribe for the Council of 50, a group of men who, in the days of Joseph Smith, Jr and Brigham Young, worked together to provide expert guidance in practical matters to the church, specifically the move westward out of the United States of America and to the Rocky Mountains.

After Smith's murder, Lee joined the bulk of the LDS Church's members in what is now Utah, and worked toward establishing several new communities.

In 1856, Lee became a U.S. Indian Agent in the Iron County area, assigned to help Native Americans establish farms. In 1858, Lee served a term as a member of the Utah Territorial Legislature.

In 1872 Lee moved from Iron County and established a ferry crossing on the Colorado River. It is still called Lee's Ferry.

Massacre at Mountain Meadows

The most pivotal event in Lee's later life happened in September, 1857. A emigrant group traveling from Arkansas, known as the Fancher party, was camped in an area of Southern Utah known as the Mountain Meadows. This area was a staging area for groups traveling to California to prepare for the long crossing of the Mohave desert.

There is definite controversy as to who initiated the attack, whether it was the local Mormons or indians, but the party was attacked in a four-day siege that later came to be known as the Mountain Meadows Massacre. Despite the controversy as to who started the siege, Lee was among the leaders of the final attack, in which approximately 120 of the Fancher party were killed, leaving only very small children as survivors. For the remainder of his life, Lee maintained that he had acted under orders from his military leaders, and under protest. After the event, Lee remained active in Mormonism and local government for several years.

In the late 1860s, various public questions arose about the exact nature of the 1857 massacre, causing difficulties for Lee and many others of those involved.

Lee was excommunicated from the LDS Church in 1870 for his part in the massacre.

In 1874, Lee was arrested and tried for the massacre, with the trial ending in a hung jury. He was tried again in 1877 and sentenced to death for leading the massacre. He never denied his own complicity, but stated he was a vocally reluctant participant and later a scapegoat meant to draw attention away from other Mormon leaders also involved. He specifically stated, however, that LDS President Brigham Young had no knowledge of the event until after it had happened.

There is another account however that should not be eliminated from consideration. It is a document widely used by historians, albeit cautiously. In the Life and Confessions of John D. Lee (p. 225), we find the statement. "I have always believed, since that day, that General George A. Smith was then visiting Southern Utah to prepare the people for the work of exterminating Captain Fancher's train of emigrants, and I now believe that he was sent for that purpose by the direct command of Brigham Young."

On March 23, 1877, Lee was executed by firing squad, on the site of the 1857 massacre. Some of his last words referred to efforts to persuade him to finger Brigham Young as responsible for the massacre: "There's no man I hate worse than a traitor. Especially I could not betray an innocent man."

In May 1961, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints posthumously reinstated Lee's membership in the church.

References

Brooks, Juanita and Cleland, Robert Glass, editors. A Mormon Chronicle: The Diaries of John D. Lee. Huntington Library Press, Reissued June 2004 (Paperback, 868pp), 3 Volumes in 1 book. ISBN 0873281780. First published in ( ).

Brooks, Juanita. John Doyle Lee: Zealot, Pioneer Builder, Scapegoat. Utah State University Press, reissue November 1992 (paperback, 404pp). ISBN 087421162X. First published in 1961.

John Doyle Lee

(1812-1877)

A man whose life was stained by tragedy, John D. Lee is perhaps the most controversial figure in Mormon history.

Born in 1812 in Kaskaskia, Illinois Territory, Lee had a tumultuous childhood. At age three, his mother died after years of lingering illnesses, leaving Lee to his alcoholic father. From age seven to sixteen Lee was raised in an uncle's family. He worked for a time as a mail carrier before assuming managerial responsibility for his uncle's farm, then worked several years as a store clerk in Galena, Illinois. Finally, Lee moved to Vandalia, Illinois, where he met and married Agatha Ann Woolsey in 1833.

It was in Vandalia that Lee and his wife encountered Mormonism. In 1837 a Mormon missionary converted the couple to the young religion, which had been formally organized only seven years before. Lee's religious passion quickly became the driving force in his life, prompting him to move in 1838 to a homestead near the Mormon town of Far West, Missouri.

The large influx of Mormons into Northwest Missouri caused enormous tensions with the non-Mormon ("gentile") population. Many of the gentiles were hostile on purely religious grounds, but they also resented the political and economic power which the cohesive Mormon community had acquired.

Individual confrontations soon exploded into near warfare involving murder, destruction of property, and cycles of raids and counter-raids between the Mormons and gentiles. Lee played an active role in many of the military conflicts, and soon became a member of the Danite Band, the formally organized Mormon militia. Finally Missouri's governor ordered the Mormons expelled or exterminated, sending an army which surrounded their community and forced the Mormon leadership to surrender.

As the Mormons began preparing for their trek eastward to Nauvoo, Illinois, Lee's religious devotion continued to strengthen. In 1838 he was promoted within the priesthood and made a member of the First Quorum of the Seventy, the body which directed the church's extensive missionary activities.

From 1839 to 1844 he spent much of his time winning converts in Illinois, Tennessee and Kentucky. His commitment impressed the church leadership, and in 1843 he was chosen to guard the home of the church's founder and prophet, Joseph Smith.

John Lee's religious fervor only grew in intensity as the young religion entered its darkest hour. In June 1844 a mob dragged Joseph Smith and his brother from their jail cell in Carthage, Illinois, and murdered them, causing a crisis of leadership within the church. In addition, there was internal dissension over the doctrine of plural marriage, which had been formally announced within the church in 1843. Lee accepted the new doctrine, soon taking five more wives, and he remained devotedly loyal to the church leadership, especially the new leader, Brigham Young, whom Lee assisted during the Mormon flight to the "Winter Quarters" near the confluence of the Platte and Missouri rivers.

Having been persecuted from their religion's birthplace in New York to Missouri and Illinois, the Mormons had by 1846 decided to seek their own Zion in the American West. This journey, the first leg of which was the removal from Nauvoo to Winter Quarters, was to take the Mormons to Utah. By 1847 the first wagons began arriving in Utah's Salt Lake valley. After serving briefly in the Mexican-American War as a member of Brigham Young's "Mormon Battalion," Lee joined the gathering masses of Zion in Utah.

For the next decade, Lee played an important role in expanding the Mormon refuge in the West. He became a prosperous farmer and businessman in Southwestern Utah, helping to establish communal mining, milling and manufacturing complexes. He became the local bishop and the Indian agent to the nearby Paiute Indians. And he continued to be a frequent visitor and trusted confidant of the church leadership in Salt Lake City.

Even in the far West, however, neither Lee nor his co-religionists were beyond the reach of the country whose persecution they had fled. In 1857, prompted by complaints about church power in the territory and a public outcry against polygamy, the United States sent an army to Utah, raising Mormon fears that the final annihilation was at hand. This invasion was the backdrop for the still-controversial Mountain Meadows Massacre, in which a wagon train of about 120 gentile immigrants, suspected of hostility toward the church, was destroyed by Mormon and Paiute forces in southwestern Utah.

Lee's involvement in the massacre -- the extent of which is still vigorously disputed and will probably never be known -- was to haunt him for the next two decades, and would ultimately lead to his execution. He had written a letter to Brigham Young shortly after the massacre which laid the blame squarely on the Paiute Indians, but even among his own neighbors rumors of Lee's guilt abounded.

In 1858 a federal judge came to southwestern Utah to investigate the massacre and Lee's part in it, but Lee went into hiding and local Mormons refused to cooperate with the investigation. Folk songs dating back to this year blamed Lee for the massacre. A warrant for his arrest remained outstanding.

Although the church sought to lower Lee's profile, by removing him as a probate judge, the Mormon leadership continued to return his immense loyalty. In 1860, Brigham Young visited one of Lee's mansions and publicly praised his personal industriousness and communal economic contributions. In 1861 the residents of Harmony, Utah, elected him as their presiding elder.

But Lee could not escape the legacy of Mountain Meadows. By the late 1860s, his diary, and letters from several of his wives, speak of persistent harassment by his Mormon neighbors for his connection with the massacre, including threatening letters and the ostracization of his children. In 1870 a Utah paper openly condemned Brigham Young for covering up the massacre. That same year Young exiled Lee to a remote part of northern Arizona and excommunicated him from the church, instructing his former confidant to "make yourself scarce and keep out of the way."

The next several years brought a continued decline in Lee's fortunes. He had several episodes of severe illness; drought followed by torrential rains destroyed many of his buildings and crops; former neighbors preyed upon his livestock and otherwise took advantage of his absence; several of his wives deserted him. Nevertheless, he was managing to eke out a living in a homesteader's cabin near the Colorado River in Northern Arizona (at one point hosting John Wesley Powell's 1869 expedition before their trip through the Grand Canyon) when a sheriff captured him in November 1874.

Lee's first trial ended inconclusively with a hung jury, probably because of the prosecution's misguided attempt to portray Brigham Young as the true mastermind of the massacre. A second trial, in which the prosecution placed the blame squarely on Lee's shoulders, ended with his conviction. The trials were the subject of enormous public attention and gave rise to many accounts of the massacre and of Lee's life.

These accounts, naturally, vary widely in their factual accuracy, but many contain the classic elements of anti-Mormon paranoia: fear of Mormon political and economic power and horror at the sexual depravity assumed to be implicit in plural marriage. Most play up the fact that Lee had numerous wives and emphasize the plight of the women and children killed and captured at Mountain Meadows. Lee himself continued to profess his innocence.

Nearly twenty years after the massacre, Lee was executed at Mountain Meadows. Although angry at Brigham Young's treatment of him, Lee's final words maintained the deep religious faith that had marked his entire adult life:

I have but little to say this morning. Of course I feel that I am at the brink of eternity, and the solemnities of eternity should rest upon my mind at the present... I am ready to die. I trust in God. I have no fear. Death has no terror.

The Mountain Meadows massacre

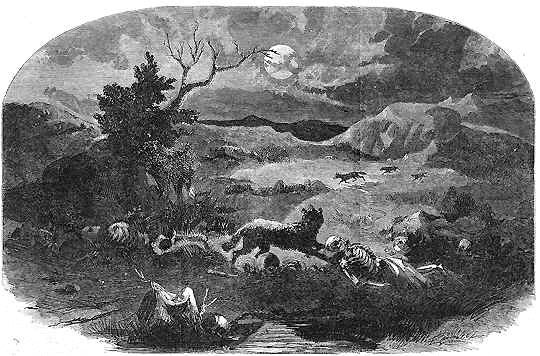

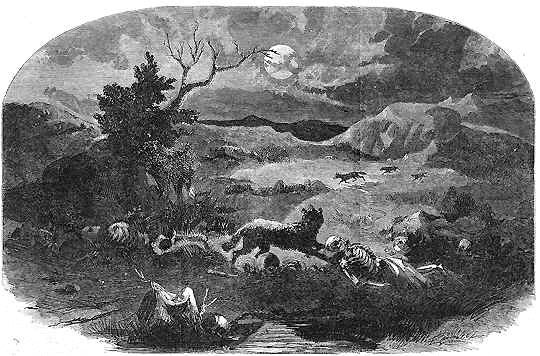

The Mountain Meadows massacre was a mass slaughter of the Fancher-Baker emigrant wagon train at Mountain Meadows, Utah Territory, by the local Mormon militia on 11 September 1857. It began as an attack, quickly turned into a siege, and eventually culminated in the execution of the unarmed emigrants after their surrender. All of the party except for seventeen children under eight years old—about 120 men, women, and children—were killed. After the massacre, the corpses of the victims were left decomposing for two years on the open plain, their children were distributed to local Mormon families, and many of their possessions auctioned off at the Latter Day Saint Cedar City tithing office.

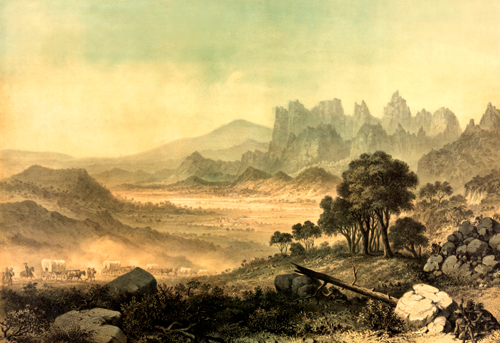

The Arkansas emigrants were traveling to California shortly before the Utah War started. Mormon leaders had been mustering militia throughout Utah Territory to fight the United States Army, which was sent to Utah to restore US authority in the territory. The emigrants stopped to rest and regroup their approximately 800 head of cattle at Mountain Meadows, a valley within the Iron County Military District of the Nauvoo Legion (the popular designation for the Mormon militia of the Utah Territory).

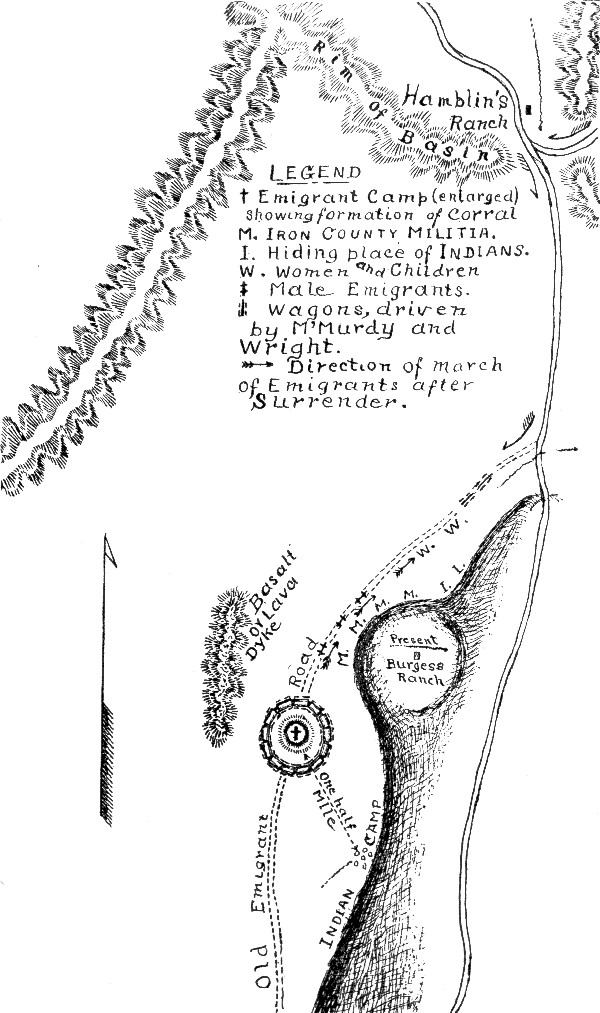

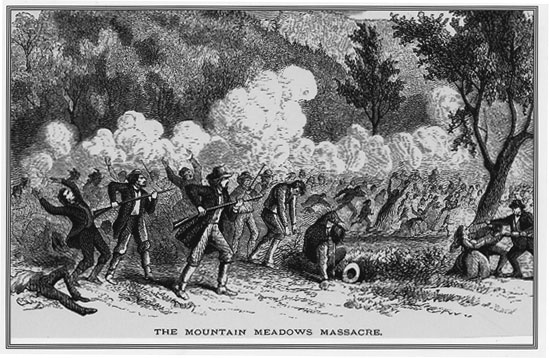

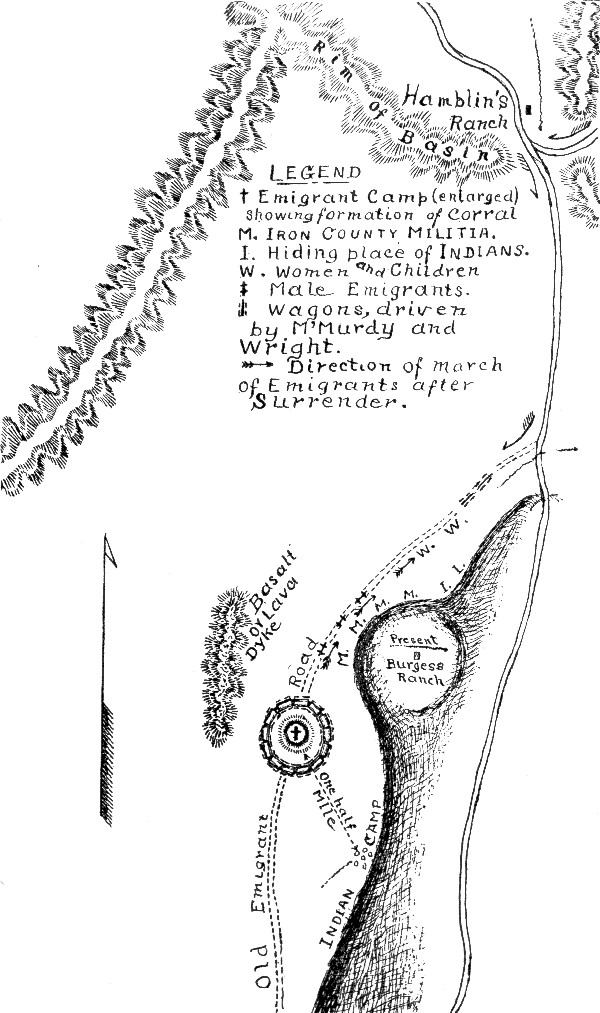

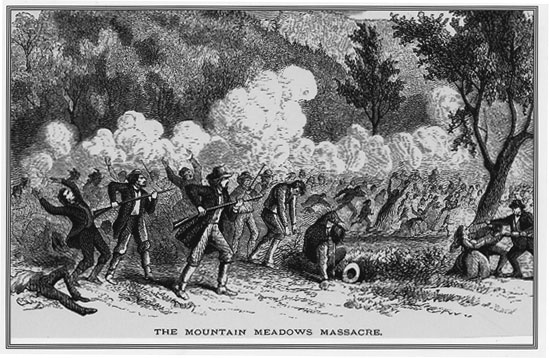

Initially intending to orchestrate an Indian massacre, local militia leaders including Isaac C. Haight and John D. Lee conspired to lead militiamen disguised as Native Americans along with a contingent of Paiute tribesmen in an attack. The emigrants fought back and a siege ensued. When the Mormons discovered that they had been identified as the attacking force by the emigrants, Col. William H. Dame, head of the Iron County Brigade of the Utah militia, ordered their annihilation.

Intending to leave no witnesses of Mormon complicity in the siege and also intending to prevent reprisals that would complicate the Utah War, militiamen induced the emigrants to surrender and give up their weapons. After escorting the emigrants out of their hasty fortification, the militiamen and their tribesmen auxiliaries executed the emigrants. Investigations, interrupted by the U.S. Civil War, resulted in nine indictments in 1874. Only John D. Lee was tried in a court of law, and after two trials, he was convicted. On March 23, 1877 a firing squad executed Lee at the massacre site.

Historians attribute the massacre to a combination of factors including war hysteria fueled by millennialism and strident Mormon teachings by top LDS leaders including Brigham Young. These teachings included doctrines about God's vengeance against those who had killed Mormon prophets, some of whom were from Arkansas. Scholars debate whether the massacre was caused by any direct involvement by Brigham Young, who was never officially charged and denied any wrongdoing. However, the predominant academic position is that Young and other church leaders helped provide the conditions which made the massacre possible.

History

Fancher-Baker party and early interaction with Mormons

In early 1857, several groups of emigrants from the northwestern Arkansas region started their trek to California, joining up on the way to form a group known as the Fancher-Baker party. The groups were mostly from Marion, Crawford, Carroll, and Johnson counties in Arkansas, and had assembled into a wagon train at Beller's Stand, south of Harrison, Arkansas to emigrate to southern California.

This group was initially referred to as both the Baker train and the Perkins train, but after being joined by other Arkansas trains and making its way west, was soon called the Fancher train (or party) after "Colonel" Alexander Fancher who, having already made the journey to California twice before, had become its main leader. By contemporary standards the Fancher party was prosperous, carefully organized, and well-equipped for the journey. They were subsequently joined along the way by families and individuals from other states, including Missouri. This group was relatively wealthy, and planned to restock its supplies in Salt Lake City, as did most wagon trains at the time. The party reached Salt Lake City with about 120 members.

At the time of the Fanchers' arrival, the Utah Territory was organized as an ostensible theocratic democracy under the lead of Brigham Young, who had established colonies along the California Trail and Old Spanish Trail. The Fanchers chose to take the southern Old Spanish Trail, which passed through southern Utah.

In August 1857, Mormon apostle George A. Smith, of Parowan, set out on a tour of southern Utah, instructing Mormons to stockpile grain. While on his return trip to Salt Lake City, Smith camped near the Fancher party on the 25th at Corn Creek, (near present-day Kanosh, Utah) 70 miles north of Parowan.

They had traveled the 165 south from Salt Lake City and Jacob Hamblin suggested that the Fanchers stop and rest their cattle at Mountain Meadows which was adjacent to his homestead. Brevet Major Carleton's report records Jacob Hamblin's account that the train was alleged to have poisoned a spring near Corn Creek (near present-day Kanosh, Utah) that killed 18 head of cattle and resulted in the deaths of two or three people (including the son of Mr Robinson) who ate the dead cattle. Most witnesses said that the Fanchers were in general a peaceful party whose members behaved well along the trail. Among Smith's party were a number of Paiute Indian chiefs from the Mountain Meadows area.

Conspiracy and siege

The Fancher party left Corn Creek and continued the 125 miles to Mountain Meadow, passing Parowan and Cedar City, southern Utah communities led respectively by Stake Presidents William H. Dame and Isaac C. Haight. Haight and Dame were, in addition, the senior regional military leaders of the Mormon militia. As the Fancher party approached, several meetings were held in Cedar City and nearby Parowan by local LDS ("Latter-Day Saints") leaders pondering how to implement Young's declaration of martial law. They decided, over the objections of some present, to "eliminate" the Fancher wagon train. Those who objected were placated with the promise of sending a rider, James Haslam, to Salt Lake City with a message to Brigham Young asking for confirmation of their decision.

The somewhat dispirited Fancher party found water and fresh grazing for its livestock after reaching grassy, mountain-ringed Mountain Meadows, a widely known stopover on the old Spanish Trail, in early September. They anticipated several days of rest and recuperation there before the next 40 miles would take them out of Utah. But, on September 7 the party was attacked by a group of Native American Paiutes and Mormon militiamen dressed as Native Americans.

The Fancher party defended itself by encircling and lowering their wagons, wheels chained together, along with digging shallow trenches and throwing dirt both below and into the wagons, which made a strong barrier. Seven emigrants were killed during the opening attack and were buried somewhere within the wagon encirclement. Sixteen more were wounded. Nearly 12 hours after the attack was initiated, Haslam was sent to Salt Lake City to inform Brigham Young. The attack continued for five days, during which the besieged families had little or no access to fresh water or game food and their ammunition was depleted.

Meanwhile, organization among the local Mormon leadership reportedly broke

down.

Killings and aftermath of the massacre

On Friday, September 11, 1857, two Mormon militiamen approached the Fancher party wagons with a white flag and were soon followed by Indian agent and militia officer John D. Lee. Lee told the battle-weary emigrants that he had negotiated a truce with the Paiutes, whereby they could be escorted safely the 36 miles back to Cedar City under Mormon protection in exchange for turning all of their livestock and supplies over to the Native Americans.

Accepting this, the emigrants were led out of their fortification. When a signal was given, the Mormon militiamen turned and executed the male members of the Fancher party standing by their side. According to Mormon sources, the militia let a group of Paiute Indians execute the women and children. The bodies of the dead were gathered and looted for valuables, and were then left in shallow graves or on the open ground. Members of the Mormon militia were sworn to secrecy. A plan was set to blame the massacre on the Indians. The militia did not kill 18 small children who were deemed too young to relate the story. These children were taken by local Mormon families. Seventeen of the children were later reclaimed by the U.S. Army and returned to relatives, while one (a girl) was not returned and lived out her life among the Mormons.

Leonard J. Arrington, an author, academic and the founder of the Mormon History Association and a devoted member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, reports that Brigham Young received the rider at his office on the same day. When he learned what was contemplated by the members of the Mormon Church in Parowan and Cedar City, he sent back a letter that the Fancher party be allowed to pass through the territory unmolested. Young's letter supposedly arrived two days too late, on September 13, 1857.

Some of the property of the dead was reportedly taken by the Native Americans involved, while large amounts of cattle and personal property was taken by the Mormons in Southern Utah. John D. Lee took charge of the livestock and other property that had been collected at the Mormon settlement at Pinto. Some of the cattle was taken to Salt Lake City and traded for boots. Some reportedly remained in the hands of John D. Lee. The remaining personal property of the Fancher party was taken to the tithing house at Cedar City and auctioned off to local Mormons.

Brigham Young, appalled at what had taken place, initially ordered an investigation into the massacre but in the end it must be acknowledged that through his own unwillingness to work with Federal authorities contributed both directly and indirectly to the blunder of justice, and was part of the reason two trials were necessary.

Investigations and prosecutions

An early investigation was conducted by Brigham Young, who interviewed John D. Lee on September 29, 1857. In 1858, Young sent a report to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs stating that the massacre was the work of Native Americans. The Utah War delayed any investigation by the U.S. federal government until 1859, when Jacob Forney, and U.S. Army Brevet Major James Henry Carleton conducted investigations. In Carleton's investigation, at Mountain Meadows he found women's hair tangled in sage brush and the bones of children still in their mothers' arms. Carleton later said it was "a sight which can never be forgotten." After gathering up the skulls and bones of those who had died, Carleton's troops buried them and erected a cairn.

Carleton interviewed a few local Mormon settlers and Paiute Indian chiefs, and concluded that there was Mormon involvement in the massacre. He issued a report in May 1859, addressed to the U.S. Assistant Adjutant-General, setting forth his findings. Jacob Forney, Superintendent of Indian Affairs for Utah, also conducted an investigation that included visiting the region in the summer of 1859 and retrieved many of the surviving children of massacre victims who had been housed with Mormon families, and gathered them in preparation of transporting them to their relatives in Arkansas. Forney concluded that the Paiutes did not act alone and the massacre would not have occurred without the white settlers, while Carleton's report to the U.S. Congress called the mass killings a "heinous crime", blaming both local and senior church leaders for the massacre.

A federal judge brought into the territory after the Utah War, Judge John Cradlebaugh, in March 1859 convened a grand jury in Provo, Utah concerning the massacre, but the jury declined any indictments. Nevertheless, Cradlebaugh conducted a tour of the Mountain Meadows area with a military escort. Cradlebaugh attempted to arrest John D. Lee, Isaac Haight, and John Higbee, but these men fled before they could be found.

Cradlebaugh publicly charged Brigham Young as an instigator to the massacre and therefore an "accessory before the fact." Possibly as a protective measure against the mistrusted federal court system, Mormon territorial probate court judge Elias Smith arrested Young under a territorial warrant, perhaps hoping to divert any trial of Young into a friendly Mormon territorial court. When no federal charges ensued, Young was apparently released.

Further investigations, cut short by the American Civil War in 1861, again proceeded in 1871 when prosecutors obtained the affidavit of militia member Phillip Klingensmith. Klingensmith had been a bishop and blacksmith from Cedar City; by the 1870s, however, he had left the church and moved to Nevada.

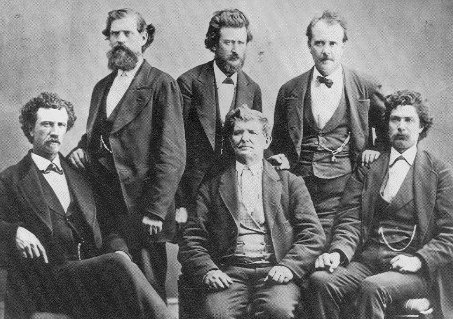

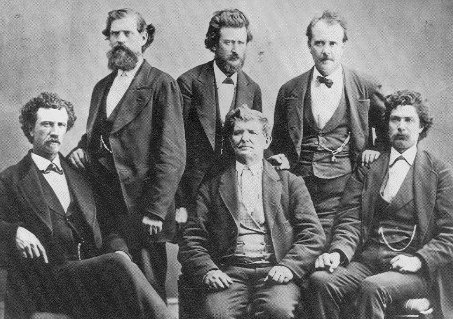

During the 1870s Lee, Dame, Philip Klingensmith and two others (Ellott Willden and George Adair, Jr.) were indicted and arrested while warrants were obtained to pursue the arrests of four others (Haight, Higbee, William C. Stewart and Samuel Jukes) who had successfully gone into hiding. Klingensmith escaped prosecution by agreeing to testify.

Brigham Young removed some participants including Haight and Lee from the LDS church in 1870. The U.S. posted bounties of $500 each for the capture of Haight, Higbee and Stewart while prosecutors chose not to pursue their cases against Dame, Willden and Adair.

Lee's first trial began on July 23, 1875 in Beaver, Utah before a jury of eight Mormons and four non-Mormons. This trial led to a hung jury on August 5, 1875. Lee's second trial began September 13, 1876, before an all-Mormon jury. The prosecution called Daniel Wells, Laban Morrill, Joel White, Samuel Knight, Samuel McMurdy, Nephi Johnson, and Jacob Hamblin. Lee also stipulated, against advice of counsel, that the prosecution be allowed to re-use the depositions of Young and Smith from the previous trial. Lee called no witnesses in his defense. This time, Lee was convicted.

At his sentencing, as required by Utah Territory statute, he was given the option of being hung, shot, or beheaded, and he chose to be shot. In 1877, before being executed by firing squad at Mountain Meadows (a fate Young believed just, but not a sufficient blood atonement, given the enormity of the crime, to get him into the celestial kingdom). Lee himself professed that he was a scapegoat for others involved.

Criticism and analysis of the massacre

Media coverage about the event

The first published report on the incident was made in 1859 by Brevet Major J.H. Carleton who had been tasked by the U.S. Army to investigate the incident and bury the still exposed corpses at Mountain Meadows. Although the massacre was covered to some extent in the media during the 1850s, the first period of intense nation-wide publicity about the massacre began around 1872, after investigators obtained the confession of Philip Klingensmith, a Mormon bishop at the time of the massacre and a private in the Utah militia.

In 1867 C.V. Waite published "An Authentic History Of Brigham Young" which described the events. In 1872, Mark Twain commented on the massacre through the lens of contemporary American public opinion in an appendix to his semi-autobiographical travel book Roughing It. In 1873, the massacre was a prominent feature of a history by T.B.H. Stenhouse, The Rocky Mountain Saints. National newspapers covered the Lee trials closely from 1874 to 1876, and his execution in 1877 was widely covered.

The massacre has been treated extensively by several historical works, beginning with Lee's own Confession in 1877, expressing his opinion that George A. Smith was sent to southern Utah by Brigham Young to direct the massacre.

In 1910, the massacre was the subject of a short book by Josiah F. Gibbs, who also attributed responsibility for the massacre to Young and Smith. The first detailed and comprehensive work using modern historical methods was The Mountain Meadows Massacre in 1950 by Juanita Brooks, a Mormon scholar who lived near the area in southern Utah. Brooks found no evidence of direct involvement by Brigham Young, but charged him with obstructing the investigation and for provoking the attack through his rhetoric.

Initially, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) denied any involvement by Mormons, and was relatively silent on the issue. In 1872, however, it excommunicated some of the participants for their role in the massacre. Since then, the LDS Church has consistently condemned the massacre, though acknowledging involvement by local Mormon leaders. In September 2007, the LDS Church published an article in its official publications marking 150 years since the tragedy occurred.

Historical theories explaining the massacre

Historians have ascribed the massacre to a number of factors, including (1) strident Mormon teachings in the years prior to the massacre, (2) war hysteria, and (3) alleged involvement of Brigham Young.

Strident Mormon teachings

Mormons, such as John D. Lee, who participated in the Mountain Meadows massacre, felt justified by strident Mormon teachings during the 1850s. However, historians debate whether or not that justification was a reasonable interpretation of Mormon theology.

For the decade prior to the Fancher party's arrival there, Utah Territory existed as a "theodemocracy" (a democratic theocracy) led by Brigham Young. During the mid-1850s, Young instituted a Mormon Reformation, intending to "lay[ing] the axe at the root of the tree of sin and iniquity", while preserving individual rights. Mormon teachings during this era were dramatic and strident.

In addition, during the prior decades, the religion had undergone a period of intense persecution in the American Midwest, and faithful Mormons moved west to escape persecution in midwestern towns. In particular, they were officially expelled from the state of Missouri during the 1838 Mormon War, during which prominent Mormon apostle David W. Patten was killed in battle. After Mormons moved to Nauvoo, Illinois, the religion's founder Joseph Smith, Jr. and his brother Hyrum Smith were assassinated in 1844. Just months before the Mountain Meadows massacre, Mormons received word that yet another "prophet" had been killed: in April 1857, apostle Parley P. Pratt was shot in Arkansas by Hector McLean, the estranged husband of one of Pratt's plural wives, Eleanor McLean Pratt. Mormon leaders immediately proclaimed Pratt as another martyr, and many Mormons held the people of Arkansas responsible.

In 1857, Mormon leaders taught that the Second Coming of Jesus was imminent, and that God would soon exact punishment against the United States for persecuting Mormons and martyring "the prophets" Joseph Smith, Jr., Hyrum Smith, Patten and Pratt. In their Endowment ceremony, faithful early Latter-day Saints took an Oath of Vengeance against the murderers of the prophets. As a result of this oath, several Mormon apostles and other leaders considered it their religious duty to kill the prophets' murderers if they ever came across them.

The sermons, blessings, and private counsel by Mormon leaders just prior to the Mountain Meadows massacre can be understood as encouraging private individuals to execute God's judgment against the wicked. In Cedar City, Utah, the teachings of church leaders were particularly strident.

Thus, historians argue that southern Utah Mormons would have been particularly affected by an unsubstantiated rumor that the Fancher wagon train had been joined by a group of eleven miners and plainsmen who called themselves "Missouri Wildcats," some of whom reportedly taunted, vandalized and "caused trouble" for Mormons and Native Americans along the route (by some accounts claiming that they had the gun that "shot the guts out of Old Joe Smith" They were also affected by the report to Brigham Young that the Fancher party was from Arkansas, and the rumor that Eleanor McLean Pratt, the apostle Pratt's plural wife, recognized one of the party as being present at her husband's murder.

War hysteria

The Mountain Meadows massacre was caused in part by events relating to the Utah War, an 1857 deployment toward the Utah Territory of the United States Army, whose arrival was peaceful. In the summer of 1857, however, the Mormons expected an all-out invasion of apocalyptic significance. From July to September 1857, Mormon leaders and their followers prepared for a siege that could have ended up similar to the seven-year Bleeding Kansas problem occurring at the time. Mormons were required to stockpile grain, and were enjoined against selling grain to emigrants for use as cattle feed. As far-off Mormon colonies retreated, Parowan and Cedar City became isolated and vulnerable outposts. Brigham Young sought to enlist the help of Indian tribes in fighting the "Americans", encouraging them to steal cattle from emigrant trains, and to join Mormons in fighting the approaching army.

In August 1857, Mormon apostle George A. Smith, of Parowan, set out on a tour of southern Utah, instructing Mormons to stockpile grain. Scholars have asserted that Smith's tour, speeches, and personal actions contributed to the fear and tension in these communities, and influenced the decision to attack and destroy the Baker-Fancher emigrant train near Mountain Meadows, Utah. He met with many of the eventual participants in the massacre, including W. H. Dame, Isaac Haight, John D. Lee and Chief Jackson, leader of a band of Pah-Utes. He noted that the militia was organized and ready to fight, and that some of them were eager to "fight and take vengeance for the cruelties that had been inflicted upon us in the States."

While on his return trip to Salt Lake City, Smith camped near the Fancher party on the 25th at Corn Creek, (near present-day Kanosh, Utah) 70 miles north of Parowan. They had traveled the 165 south from Salt Lake City and Jacob Hamblin suggested that the Fanchers stop and rest their cattle at Mountain Meadows which was adjacent to his homestead.

Brevet Major Carleton's report records Jacob Hamblin's account that the train was alleged to have poisoned a spring near Corn Creek (near present-day Kanosh, Utah) that killed 18 head of cattle and resulted in the deaths of two or three people (including the son of Mr Robinson) who ate the dead cattle. Most witnesses said that the Fanchers were in general a peaceful party whose members behaved well along the trail. Among Smith's party were a number of Paiute Indian chiefs from the Mountain Meadows area.

When Smith returned to Salt Lake, Brigham Young met with these leaders on September 1, 1857 and encouraged them to fight against the "Americans" in the anticipated clash with the U.S. Army. They were also "given" all of the livestock then on the road to California, which included that belonging to the Fancher party. The Indian chiefs were reluctant, and at least one objected they had previously been told not to steal, and declined the offer. Some scholars theorize, however, that the leaders returned to Mountain Meadows and participated in the massacre. However, it is uncertain whether they would have had time to do so.

Alleged involvement of Brigham Young

Historians agree that Brigham Young played a role in provoking the massacre, at least unwittingly, and in concealing its evidence after the fact; however, they debate whether or not Young knew about the planned massacre ahead of time, and whether or not he initially condoned it, before later taking a strong public stand against it. Young's use of inflammatory and violent language in response to the Federal expedition added to the tense atmosphere at the time of the attack. After the massacre, Young stated in public forums that God had taken vengeance on the Fancher party.

It is unclear whether Young held this view because he believed that this specific group posed an actual threat to colonists or because he believed that the group was directly responsible for past crimes against Mormons. According to historian MacKinnon, "After the [Utah] war, U.S. President James Buchanan implied that face-to-face communications with Brigham Young might have averted the conflict, and Young argued that a north-south telegraph line in Utah could have prevented the Mountain Meadows Massacre." MacKinnon suggests that hostilities could have been avoided if Young had traveled east to Washington D.C. to resolve governmental problems instead of taking a five week trip north on the eve of the Utah War for church related reasons.

Remembrances

Starting in 1988 descendants of both the Fancher party victims and the Mormon participants collaborated to design and dedicate a monument to replace the neglected and crumbling marker on the site. There are now three monuments to the massacre. Two of these are at Mountain Meadows. Mountain Meadows Association built a monument in 1990 which is maintained by the Utah State Division of Parks and Recreation. In 1999 the Mormon Church built and maintains a second monument.

A monument placed in the central square of Harrison, Arkansas is a replica of Carleton's original marker maintained by the Mountain Meadows Massacre Monument Foundation.

Confession of John D. Lee

LAST CONFESSION AND STATEMENT OF JOHN D. LEE

WRITTEN AT HIS DICTATION AND DELIVERED TO WILLIAM W. BISHOP, ATTORNEY FOR LEE, WITH A REQUEST THAT THE SAME BE PUBLISHED.

Page 213

AS A DUTY to myself, my family, and mankind at large, I propose to give a full and true statement of all that I know and all that I did in that unfortunate affair, which has cursed my existence, and made me a wanderer from place to place for the last nineteen years, and which is known to the world as the MOUNTAIN MEADOWS MASSACRE.

I have no vindictive feeling against any one; no enemies to punish by this statement; and no friends to shield by keeping back, or longer keeping secret, any of the facts connected with the Massacre.

I believe that I must tell all that I do know, and tell everything just as the same transpired. I shall tell the truth and permit the public to judge who is most to blame for the crime that I am accused of committing. I did not act alone; I had many to assist me at the Mountain Meadows. I believe that most of those who were connected with the Massacre, and took part in the lamentable transaction that has blackened the character of all who were aiders or abettors in the same, were acting under the impression that they were performing a religious duty.

I know all were acting under the orders and by the command of their Church leaders; and I firmly believe that the most of those who took part in the proceedings, considered it a religious duty to unquestioningly obey the orders which they had received. That they acted from a sense of duty to the Mormon Church, I

Page 214

never doubted. Believing that those with me acted from a sense of religious duty on that occasion, I have faithfully kept the secret of their guilt, and remained silent and true to the oath of secrecy which we took on the bloody field, for many long and bitter years. I have never betrayed those who acted with me and participated in the crime for which I am convicted, and for which I am to suffer death.

My attorneys, especially Wells Spicer and Wm. W. Bishop, have long tried, but tried in vain, to induce me to tell all I knew of the massacre and the causes which led to it. I have heretofore refused to tell the tale. Until the last few days I had in tended to die, if die I must, without giving one word to the public concerning those who joined willingly, or unwillingly, in the work of destruction at Mountain Meadows.

To hesitate longer, or to die in silence, would be unjust and cowardly. I will not keep the secret any longer as my own, but will tell all I know.

At the earnest request of a few remaining friends, and by the advice of Mr. Bishop, my counsel, who has defended me thus far with all his ability, notwithstanding my want of money with which to pay even his expenses while attending to my case, I have concluded to write facts as I know them to exist.

I cannot go before the Judge of the quick and the dead with out first revealing all that I know, as to what was done, who ordered me to do what I did do, and the motives that led to the commission of that unnatural and bloody deed.

The immediate orders for the killing of the emigrants came from those in authority at Cedar City. At the time of the massacre, I and those with me, acted by virtue of positive orders from Isaac C. Haight and his associates at Cedar City. Before I started on my mission to the Mountain Meadows, I was told by Isaac C. Haight that his orders to me were the result of full consultatation [sic] with Colonel William H. Dame and all in authority. It is a new thing to me, if the massacre was not decided on by the head men of the Church, and it is a new thing for Mormons to condemn those who committed the deed.

Being forced to speak from memory alone, without the aid of my memorandum books, and not having time to correct the statements that I make, I will necessarily give many things out of their regular order. The superiority that I claim for my statement is this:

Page 215

ALL THAT I DO SAY IS TRUE AND NOTHING BUT THE TRUTH.

I will begin my statement by saying, I was born on the 6th day of September, A. D. 1812, in the town of Kaskaskia, Randolph County, State of Illinois. I am therefore in the sixty-fifth year of my age.

I joined the Mormon Church at Far West, Mo., about thirty-nine years ago. To be with that Church and people I left my home on Luck Creek, Fayette County, Illinois, and went and joined the Mormons in Missouri, before the troubles at Gallatin, Far West and other points, between the Missourians and Mormons. I shared the fate of my brother Mormons, in being mistreated, arrested, robbed and driven from Missouri in a destitute condition, by a wild and fanatical mob. But of all this I shall speak in my life, which I shall write for publication if I have time to do so.

I took an active part with the leading men at Nauvoo in building up that city. I induced many Saints to move to Nauvoo, for the sake of their souls. I traveled and preached the Mormon doctrine in many States. I was an honored man in the Church, and stood high with the Priesthood, until the last few years. I am now cut off from the Church for obeying the orders of my superiors, and doing so without asking questions--for doing as my religion and my religious teachers had taught me to do. I am now used by the Mormon Church as a scape-goat to carry the sins of that people. My life is to be taken, so that my death may stop further enquiry into the acts of the members who are still in good standing in the Church. Will my death satisfy the nation for all the crimes committed by Mormons, at the command of the Priesthood, who have used and now have deserted me? Time will tell. I believe in a just God, and I know the day will come when others must answer for their acts, as I have had to do.

I first became acquainted with Brigham Young when I went to Far West, Mo., to join the Church, in 1837. I got very intimately acquainted with all the great leaders of the Church. I was adopted by Brigham Young as one of his sons, and for many years I confess I looked upon him as an inspired and holy man. While in Nauvoo I took an active part in all that was done for the Church or the city. I had charge of the building of the "Seventy Hall;" I was 7th Policeman. My duty as a police

Page 216

man was to guard the residence and person of Joseph Smith, the Prophet. After the death of Joseph and Hyrum I was ordered to perform the same duty for Brigham Young. When Joseph Smith was a candidate for the Presidency of the United States I went to Kentucky as the chairman of the Board of Elders, or head of the delegation, to secure the vote of that State for him. When I returned to Nauvoo again I was General Clerk and Recorder for the Quorum of the Seventy. I was also head or Chief Clerk for the Church, and as such took an active part in organizing the Priesthood into the order of Seventy after the death of Joseph Smith.

After the destruction of Nauvoo, when the Mormons were driven from the State of Illinois, I again shared the fate of my brethren, and partook of the hardships and trials that befel [sic] them from that day up to the settlement of Salt Lake City, in the then wilderness of the nation. I presented Brigham Young with seventeen ox teams, fully equipped, when he started with the people from Winter Quarters to cross the plains to the new resting place of the Saints. He accepted them and said, "God bless you, John." But I never received a cent for them--I never wanted pay for them, for in giving property to Brigham Young I thought I was loaning it to the Lord.

After reaching Salt Lake City I stayed there but a short time, when I went to live at Cottonwood, where the mines were afterwards discovered by General Connor and his men during the late war.

I was just getting fixed to live there, when I was ordered to go out into the interior and aid in forming new settlements, and opening up the country. I then had no wish or desire, save that to know and be able to do the will of the Lord's anointed, Brigham Young, and until within the last few years I have never had a wish for anything else except to do his pleasure, since I became his adopted son. I believed it my duty to obey those in authority. I then believed that Brigham Young spoke by direction of the God of Heaven. I would have suffered death rather than have disobeyed any command of his. I had this feeling until he betrayed and deserted me. At the command of Brigham Young, I took one hundred and twenty-one men, went in a southern direction from Salt Lake City, and laid out and built up Parowan. George A. Smith was the leader and chief man in authority in that settlement. I acted under him

Page 217

as historian and clerk of the Iron County Mission, until January, 1851. I went with Brigham Young, and acted as a committee man, and located Provo, St. George, Fillmore, Parowan and other towns, and managed the location of many of the settlements in Southern Utah.

In 1852, I moved to Harmony, and built up that settlement. I remained there until the Indians declared war against the whites and drove the settlers into Cedar City and Parowan, for protection, in the year 1853.

I removed my then numerous family to Cedar City, where I was appointed a Captain of the militia, and commander of Cedar City Military Post.

I had commanded at Cedar City about one year, when I was ordered to return to Harmony, and build the Harmony Fort. This order, like all other orders, came from Brigham Young. When I returned to Harmony and commenced building the fort there, the orders were given by Brigham Young for the reorganization of the military at Cedar City. The old men were requested to resign their offices, and let younger men be appointed in their place. I resigned my office of Captain, but Isaac C. Haight and John M. Higbee refued [sic] to resign, and continued to hold on as Majors in the Iron Militia.

After returning to Harmony, I was President of the civil and local affairs, and Rufus Allen was President of that Stake of Zion, or head of the Church affairs.

I soon resigned my position as President of civil affairs, and became a private citizen, and was in no office for some time. In fact, I never held any position after that, except the office of Probate Judge of the County (which office I held before and after the massacre), and member of the Territorial Legislature, and Delegate to the Constitutional Convention which met and adopted a constitution for the State of Deseret, after the massacre.

I will here state that Brigham Young honored me in many ways after the affair at Mountain Meadows was fully reported to him by me, as I will more fully state hereafter in the course of what I have to relate concerning that unfortunate transaction.

Klingensmith, at my first trial, and White, at my last trial, swore falsely when they say that they met me near Cedar City, the Sunday before the massacre. They did not meet me as they have sworn, nor did they meet me at all on that occasion or on

Page 218

any similar occasion. I never had the conversations with them that they testify about. They are both perjurers, and bore false testimony against me.

There has never been a witness on the stand against me 'that has testified to the whole truth. Some have told part truth, while others lied clear through, but all of the witnesses who were at the massacre have tried to throw all the blame on me, and to protect the other men who took part in it.

About the 7th of September, 1857, I went to Cedar City from my home at Harmony, by order of President Haight. I did not know what he wanted of me, but he had ordered me to visit him and I obeyed. If I remember correctly, it was on Sunday evening that I went there. When I got to Cedar City, I met Isaac C. Haight on the public square of the town. Haight was then President of that Stake of Zion, and the highest man in the Mormon priesthood in that country, and next to Wm. H. Dame in all of Southern Utah, and as Lieutenant Colonel he was second to Dame in the command of the Iron Military District. The word and command of Isaac C. Haight were the law in Cedar City, at that time, and to disobey his orders was certain death; be they right or wrong, no Saint was permitted to question them, their duty was obedience or death.

When I met Haight, I asked him what he wanted with me. He said he wanted to have a long talk with me on private and particular business. We took some blankets and went over to the old Iron Works, and lay there that night, so that we could talk in private and in safety. After we got to the Iron Works, Haight told me all about the train of emigrants. He said (and I then believed every word that be spoke, for I believed it was an impossible thing for one so high in the Priesthood as he was, to be guilty of falsehood) that the emigrants were a rough and abusive set of men. That they had, while traveling through Utah, been very abusive to all the Mormons they met. That they had insulted, outraged, and ravished many of the Mormon women. That the abuses heaped upon the people by the emigrants during their trip from Provo to Cedar City, had been constant and shameful; that they had burned fences and destroyed growing crops; that at many points on the road they had poisoned the water, so that all people and stock that drank of the water became sick, and many had died from the effects of poison. That these vile Gentiles publicly proclaimed that they had the very

Page 219

pistol with which the Prophet, Joseph Smith, was murdered, and had threatened to kill Brigham Young and all of the Apostles. That when in Cedar City they said they would have friends in Utah who would hang Brigham Young by the neck until he was dead, before snow fell again in the Territory.. They also said that Johnston was coming, with his army, from the East, and they were going to return from California with soldiers, as soon as possible, and would then desolate the land, and kill every d--d Mormon man, woman and child that they could find in Utah. That they violated the ordinances of the town of Cedar, and had, by armed force, resisted the officers who tried to arrest them for violating the law. That after leaving Cedar City the emigrants camped by the company, or cooperative field, just below Cedar City, and burned a large portion of the fencing, leaving the crops open to the large herds of stock in the surrounding country. Also that they had given poisoned meat to the Corn Creek tribe of Indians, which had killed several of them, and their Chief, Konosh, was on the trail of the emigrants, and would soon attack them. All of these things, and much more of a like kind, Haight told me as we lay in the dark at the old Iron Works. I believed all that he said, and, thinking that he had full right to do all that he wanted to do, I was easily induced to follow his instructions.

Haight said that unless something was done to prevent it, the emigrants would carry out their threats and rob every one of the outlying settlements in the South, and that the whole Mormon people were liable to be butchered by the troops that the emigrants would bring back with them from California. I was then told that the Council had held a meeting that day, to consider the matter, and that it was decided by the authorities to arm the Indians, give them provisions and ammunition, and send them after the emigrants, and have the Indians give them a brush, and if they killed part or all of them, so much the better.

I said, "Brother Haight, who is your authority for acting in this way?"

He replied, "It is the will of all in authority. The emigrants have no pass from any one to go through the country, and they are liable to be killed as common enemies, for the country is at war now. No man has a right to go through this country without a written pass."

We lay there and talked much of the night, and during that

Page 220

time Haight gave me very full instructions what to do, and how to proceed in the whole affair. He said he had consulted with Colonel Dame, and every one agreed to let the Indians use up the whole train if they could. Haight then said:

"I expect you to carry out your orders."

I knew I had to obey or die. I had no wish to disobey, for I then thought that my superiors in the Church were the mouth pieces of Heaven, and that it was an act of godliness for me to obey any and all orders given by them to me, without my asking any questions.

My orders were to go home to Harmony, and see Carl Shirts, my son-in-law, an Indian interpreter, and send him to the Indians in the South, to notify them that the Mormons and Indians were at war with the "Mericats" (as the Indians called all whites that were not Mormons) and bring all the Southern Indians up and have them join with those from the North, so that their force would be sufficient to make a successful attack on the emigrants.

It was agreed that Haight would send Nephi Johnson, another Indian interpreter, to stir up all the other Indians that he could find, in order to have a large enough force of Indians to give the emigrants a good hush. He said, "These are the orders that have been agreed upon by the Council, and it is in accordance with the feelings of the entire people."

I asked him if it would not have been better to first send to Brigham Young for instructions, and find out what he thought about the matter.

"No," said Haight, "that is unnecessary, we are acting by orders. Some of the Indians are now on the war-path, and all of them must be sent out; all must go, so as to make the thing a success.

It was then intended that the Indians should kill the emigrants, and make it an Indian massacre, and not have any whites interfere with them. No whites were to be known in the matter, it was to be all done by the Indians, so that it could be laid to them, if any questions were ever asked about it. I said to Haight:

"You know what the Indians are. They will kill all the party, women and children, as well as the men, and you know we are sworn not to shed innocent blood."

"Oh h--l!" said he, "there will not be one drop of innocent

Page 221

blood shed, if every one of the d--d pack are killed, for they are the worse lot of out-laws and ruffians that I ever saw in my life."

We agreed upon the whole thing, how each one should act, and then left the iron works, and went to Haight's house and, got breakfast.

After breakfast I got ready to start, and Haight said to me:

"Go, Brother Lee, and see that the instructions of those in authority are obeyed, and as you are dutiful in this, so shall your reward be in the kingdom of God, for God will bless those who willingly obey counsel, and make all things fit for the people in these last days."

I left Cedar City for my home at Harmony, to carry out the instructions that I had received from my superior.

I then believed that he acted by the direct order and command of William H. Dame, and others even higher in authority than Colonel Dame. One reason for thinking so was from a talk I had only a few days before, with Apostle George A. Smith, and he had just then seen Haight, and talked with him, and I knew that George A. Smith never talked of things that Brigham Young had not talked over with him before-hand. Then the Mormons were at war with the United States, and the orders to the Mormons had been all the time to kill and waste away our enemies, but lose none of our people. These emigrants were from the section of country most hostile to our people, and I believed then as I do now, that it was the will of every true Mormon in Utah, at that time, that the enemies of the Church should be killed as fast as possible, and that as this lot of people had men amongst them that were supposed to have helped kill the Prophets in the Carthage jail, the killing of all of them would be keeping our oaths and avenging the blood of the Prophets.

In justice to myself I will give the facts of my talk with George A. Smith.

In the latter part of the month of August, 1857, about ten days before the company of Captain Fancher, who met their doom at Mountain Meadows, arrived at that place, General George A. Smith called on me at one of my homes at Washington City, Washington County, Utah Territory, and wished me to take him round by Fort Clara, via Pinto Settlements, to Hamilton Fort, or Cedar City. He said,

"I have been sent down here by the old Boss, Brigham Young,

Page 222

to Instruct the brethren of the different settlements not to sell any of their grain to our enemies. And to tell them not, to feed it to their animals, for it will all be needed by ourselves. I am also to instruct the brethren to prepare for a big fight, for the enemy is coming in large force to attempt our destruction. But Johnston's army will not be allowed to approach our settlements from the east. God is on our side and will fight our battles for us, and deliver our enemies into our hands. Brigham Young has received revelations from God, giving him the right and the power to call down the curse of God on all our enemies who attempt to invade our Territory. Our greatest danger lies in the people of California--a class of reckless miners who are strangers to God and his righteousness. They are likely to come upon us from the south and destroy the small settlements. But we will try and outwit them before we suffer much damage. The people of the United States who oppose our Church and people are a mob, from the President down, and as such it is impossible for their armies to prevail against the Saints who have gathered here in the mountains."

He continued this kind of talk for some hours to me and my friends who were with me.

General George A. Smith held high rank as a military leader. He was one of the twelve apostles of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, and as such he was considered by me to be an inspired man. His orders were to me sacred commands, which I considered it my duty to obey, without question or hesitation.

I took my horses and carriage and drove with him to either Hamilton Fort or Cedar City, visiting the settlements with him, as he had requested. I did not go to hear him preach at any of our stopping places, nor did I pay attention to what he said to the leaders in the settlements.

The day we left Fort Clara, which was then the headquarters of the Indian missionaries under the presidency of Jacob Hamblin, we stopped to noon at the Clara River. While there the Indians gathered around us in large numbers, and were quite saucy and impudent. Their chiefs asked me where I was going and who I had with me. I told them that he was a big captain.

"Is he, a Mericat Captain?"

"No," I said, "he is a Mormon."

Page 223

The Indians then wanted to know more. They wanted to have a talk.

The General told me to tell the Indians that the Mormons were their friends, and that the Americans were their enemies, and the enemies of the Mormons, too; that he wanted the Indians to remain the fast friends of the Mormons, for the Mormons were all friends to the Indians; that the Americans had a large army just east of the mountains, and intended to come over the mountains into Utah and kill all of the Mormons and Indians in Utah Territory; that the Indians must get ready and keep ready for war against all of the Americans, and keep friendly with the Mormons and obey what the Mormons told them to do--that this was the will of the Great Spirit; that if the Indians were true to the Mormons and would help them against their enemies, then the Mormons would always keep them from want and sickness and give them guns and ammunition to hunt and kill game with, and would also help the Indians against their enemies when they went into war.

This talk pleased the Indians, and they agreed to all that I asked them to do.

I saw that my friend Smith was a little nervous and fearful of the Indians, notwithstanding their promises of friendship. To relieve him of his anxiety I hitched up and started on our way, as soon as I could do so without rousing the suspicions of the Indians.

We had ridden along about a mile or so when General Smith said,

"Those are savage looking fellows. I think they would make it lively for an emigrant train if one should come this way."

I said I thought they would attack any train that would come in their way. Then the General was in a deep study for some time, when he said,

"Suppose an emigrant train should come along through this southern country, making threats against our people and bragging of the part they took in helping kill our Prophets, what do you think the brethren would do with them? Would they be permitted to go their way, or would the brethren pitch into them and give them a good drubbing?"

I reflected a few moments, and then said,

"You know the brethren are now under the influence of the late reformation, and are still red-hot for the gospel.

Page 224

The brethren believe the government wishes to destroy them. I really believe that any train of emigrants that may come through here will be attacked, and. probably all destroyed. I am sure they would be wiped out if they had been making threats again our people. Unless emigrants have a pass from Brigham Young, or some one in authority, they will certainly never get safely through this country."

My reply pleased him very much, and he laughed heartily, and then said,

"Do you really believe the brethren would make it lively for such a train?"

I said, "Yes, sir, I know they will, unless they are protected by a pass, and I wish to inform you that unless you want every train captured that comes through here, you must inform Governor Young that if he wants emigrants to pass, without being molested, he must send orders to that effect to Colonel Wm. H. Dame or Major Isaac C. Haight, so that they can give passes to the emigrants, for their passes will insure safety, but nothing else will, except the positive orders of Governor Young, as the people are all bitter against the Gentiles, and full of religious zeal, and anxious to avenge the blood of the Prophets."

The only reply he made was to the effect that on his way down from Salt Lake City he had had a long talk with Major Haight on the same subject, and that Haight had assured him, and given him to understand, that emigrants who came along without a pass from Governor Young could not escape from the Territory.

We then rode along in silence for some distance, when he again turned to me and said,

"Brother Lee, I am satisfied that the brethren are under the full influence of the reformation, and I believe they will do just as you say they will with the wicked emigrants that come through the country making threats and abusing our people."

I repeated my views to him, but at much greater length, giving my reasons in full for thinking that Governor Young should give orders to protect all the emigrants that he did not wish destroyed. I went into a full statement of the wrongs of our people, and told him that the people were under the blaze of the reformation, full of wild fire and fanaticism, and that to shed the blood of those who would dare to speak against the Mormon Church or its leaders, they would consider doing the

Page 225

will of God, and that the people would do it as willingly and cheerfully as they would any other duty. That the apostle Paul, when he started forth to persecute the followers of Christ, was not any more sincere than every Mormon was then, who lived in Southern Utah.

My words served to cheer up the General very much; he was greatly delighted, and said,

"I am glad to hear so good an account of our people. God will bless them for all that they do to build up His Kingdom in the last days."

General Smith did not say one word to me or intimate to me, that he wished any emigrants to pass in safety through the Territory. But he led me to believe then, as I believe now, that he did want, and expected every emigrant to be killed that undertook to pass through the Territory while we were at war with the Government. I thought it was his mission to prepare the people for the bloody work.

I have always believed, since that day, that General George A. Smith was then visiting Southern Utah to prepare the people for the work of exterminating Captain Fancher's train of emigrants, and I now believe that he was sent for that purpose by the direct command of Brigham Young.

I have been told by Joseph Wood, Thomas T. Willis, and many others, that they heard George A. Smith preach at Cedar City during that trip, and that he told the people of Cedar City that the emigrant's were coming, and he told them that they must not sell that company any grain or provisions of any kind, for they were a mob of villains and outlaws, and the enemies of God and the Mormon people.

Sidney Littlefield, of Panguitch, has told me that he was knowing to the fact of Colonel Wm. H. Dame sending orders from Parowan to Maj. Haight, at Cedar City, to exterminate the Francher [sic] outfit, and to kill every emigrant without fail. Littlefield then lived at Parowan, and Dame was the Presiding Bishop. Dame still has all the wives he wants, and is a great friend of Brigham Young.

The knowledge of how George A. Smith felt toward the emigrants, and his telling me that he had a long talk with Haight on the subject, made me certain that it was the wish of the Church authorities that Francher [sic] and his train should be wiped out, and knowing all this, I did not doubt then, and I do not

Page 226

doubt it now, either, that Haight was acting by full authority from the Church leaders, and that the orders he gave to me were just the orders that he had been directed to give, when he ordered me to raise the Indians and have them attack the emigrants.

I acted through the whole matter in a way that I considered it my religious duty to act, and if what I did was a crime, it was a crime of the Mormon Church, and not a crime for which I feel individually responsible.

I must here state that Klingensmith was not in Cedar City that Sunday night. Haight said he had sent Klingensmith and others over towards Pinto, and around there, to stir up the Indians and force them to attack the emigrants.

On my way from Cedar City to my home at Harmony, I came up with a large band of Indians under Moquetas and Big Bill, two Cedar City Chiefs; they were in their war paint, and fully equipped for battle. They halted when I came up and said they had had a big talk with Haight, Higby and Klingensmith, and had got orders from them to follow up the emigrants and kill them all, and take their property as the spoil of their enemies.

These Indians wanted me to go with them and command their forces. I told them that I could not go with them that evening, that I had orders from Haight, the big Captain, to send other Indians on the war-path to help them kill the emigrants, and that I must attend to that first; that I wanted them to go on near where the emigrants were and camp until the other Indians joined them; that I would meet them the next day and lead

them.

This satisfied them, but they wanted me to send my little Indian boy, Clem, with them. After some time I consented to let Clem go with them, and I returned home.

When I got home I told Carl Shirts what the orders were that Haight had sent to him. Carl was naturally cowardly and was not willing to go, but I told him the orders must be obeyed. He then started off that night, or early next morning, to stir up the Indians of the South, and lead them against the emigrants. The emigrants were then camped at Mountain Meadows.

The Indians did not obey my instructions. They met, several hundred strong, at the Meadows, and attacked the emigrants Tuesday morning, just before daylight, and at the first fire, as I afterwards learned, they killed seven and wounded sixteen of

Page 227

the emigrants. The latter fought bravely, and repulsed the Indians, killing some of them and breaking the knees of two war chiefs, who afterwards died.

The news of the battle was carried all over the country by Indian runners, and the excitement was great in all the small settlements. I was notified of what had taken place, early Tuesday morning, by an Indian who came to my house and gave me a full account of all that had been done. The Indian said it was the wish of all the Indians that I should lead them, and that I must go back with him to the camp.

I started at once, and by taking the Indian trail over the mountain, I reached the camp in about twelve miles from Harmony. To go round by the wagon road it would have been between forty and fifty miles.

When I reached the camp I found the Indians in a frenzy of excitement. They threatened to kill me unless I agreed to lead them against the emigrants, and help them kill them. They also said they had been told that they could kill the emigrants without danger to themselves, but they had lost some of their braves, and others were wounded, and unless they could kill all the "Mericats," as they called them, they would declare war against the Mormons and kill every one in the settlements.

I did as well as I could under the circumstances. I was the only white man there, with a wild and excited band of several hundred Indians. I tried to persuade them that all would be well, that I was their friend and would see that they bad their revenge, if I found out that they were entitled to revenge.

My talk only served to increase their excitement, and being afraid that they would kill me if I undertook to leave them, and I would not lead them against the emigrants, so I told them that I would go south and meet their friends, and hurry them up to help them. I intended to put a stop to the carnage if I had the power, for I believed that the emigrants had been sufficiently punished for what they had done, and I felt then, and always have felt that such wholesale murdering was wrong.

At first the Indians would not consent for me to leave them, but they finally said I might go and meet their friends.

I then got on my horse and left the Meadows, and went south.

I had gone about sixteen miles, when I met Carl Shirts with about one hundred Indians, and a number of Mormons from the southern settlements. They were going to the scene of the con-

Page 228

flict. How they learned of the emigrants being at the Meadows I never knew, but they did know it, and were there fully armed, and determined to obey orders.

Amongst those that I remember to have met there, were Samuel Knight, Oscar Hamblin, William Young, Carl Shirts, Harrison Pearce, James Pearce, John W. Clark, William Slade, Sr., James Matthews, Dudley Leavitt, William Hawley, (now a resident of Fillmore, Utah Territory,) William Slade, Jr., and two others whose names I have forgotten. I think they were George W. Adair and John Hawley. I know they were at the Meadows at the time of the massacre, and I think I met them that night south of the Meadows, with Samuel Knight and the others.

The whites camped there that night with me, but most of the Indians rushed on to their friends at the camp on the Meadows.

I reported to the whites all that had taken place at the Meadows, but none of them were surprised in the least. They all seemed to know that the attack was to be made, and all about it. I spent one of the most miserable nights there that I ever passed in my life. I spent much of the night in tears and at prayer. I wrestled with God for wisdom to guide me. I asked for some sign, some evidence that would satisfy me that my mission was of Heaven, but I got no satisfaction from my God.

In the morning we all agreed to go on together to Mountain Meadows, and camp there, and then send a messenger to Haight, giving him full instructions of what had been done, and to ask him for further instructions. We knew that the original plan was for the Indians to do all the work, and the whites to do nothing, only to stay back and plan for them, and encourage them to do the work. Now we knew the Indians could not do the work, and we were in a sad fix.

I did not then know that a messenger had been sent to Brigham Young for instructions. Haight had not mentioned it to me. I now think that James Haslem was sent to Brigham Young, as a sharp play on the part of the authorities to protect themselves, if trouble ever grew out of the matter.

We went to the Meadows and camped at the springs, about half a mile from the emigrant camp. There was a larger number of Indians there then, fully three hundred, and I think as many as four hundred of them. The two Chiefs who were shot in the knee were in a bad fix. The Indians had killed a number of the emigrants' horses, and about sixty or seventy head

Page 229

of cattle were lying dead on the Meadows, which the Indians bad killed for spite and revenge.

Our company killed a small beef for dinner, and after eating a hearty meal of it we held a council and decided to send a messenger to Haight. I said to the messenger, who was either Edwards or Adair, (I cannot now remember which it was), "Tell Haight, for my sake, for the people's sake, for God's sake, send me help to protect and save these emigrants, and pacify the Indians."

The messenger started for Cedar City, from our camp on the Meadows, about 2 o'clock P. M.

We all staid [sic] on the field, and I tried to quiet and pacify the Indians, by telling them that I had sent to Haight, the Big Captain, for orders, and when he sent his order I would know what to do. This appeared to satisfy the Indians, for said they,

"The Big Captain will send you word to kill all the Mericats."

Along toward evening the Indians again attacked the emigrants. This was Wednesday. I heard the report of their guns, and the screams of the women and children in the corral.

This was more than I could stand. So I ran with William Young and John Mangum, to where the Indians were, to stop the fight. While on the way to them they fired a volley, and three balls from their guns cut my clothing. One ball went through my hat and cut my hair on the side of my head. One ball went through my shirt and leaded my shoulder, the other cut my pants across my bowels. I thought this was rather warm work, but I kept on until I reached the place where the Indians were in force. When I got to them, I told them the Great Spirit would be mad at them if they killed the women and children. I talked to them some time, and cried with sorrow when I saw that I could not pacify the savages.

When the Indians saw me in tears, they called me "Yaw Guts," which in the Indian language means "cry baby," and to this day they call me by that name, and consider me a coward.

Oscar Hamblin was a fine interpreter, and he came to my aid and helped me to induce the Indians to stop the attack. By his help we got the Indians to agree to be quiet until word was returned from Haight. (I do not know now but what the messenger started for Cedar City, after this night attack, but I was so worried and perplexed at that time, and so much has hap-

Page 230

pened to distract my thoughts since then, that my mind is not clear on that subject.)

On Thursday, about noon, several men came to us from Cedar City. I cannot remember the order in which all of the people came to the Meadows, but I do recollect that at this time and in this company Joel White, William C. Stewart, Benjamin Arthur, Alexander Wilden, Charles Hopkins and ---- Tate, came to us at the camp at the Springs. These men said but little, but every man seemed to know just what he was there for. As our messenger had gone for further orders, we moved our camp about, four hundred yards further up the valley on to a hill, where we made camp as long as we staid [sic] there. I soon learned that the whites were as wicked at heart as the Indians, for every little while during that day I saw white men. taking aim and shooting at the emigrants' wagons. They said they were doing it to keep in practice and to help pass off the time.