Rodney James Alcala

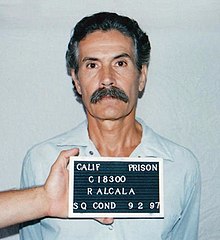

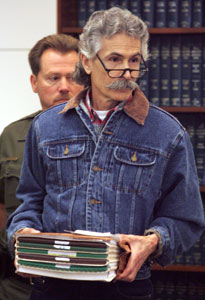

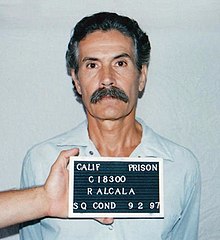

Rodney James Alcala is indicted in Orange County Superior Court September 19, 2005.

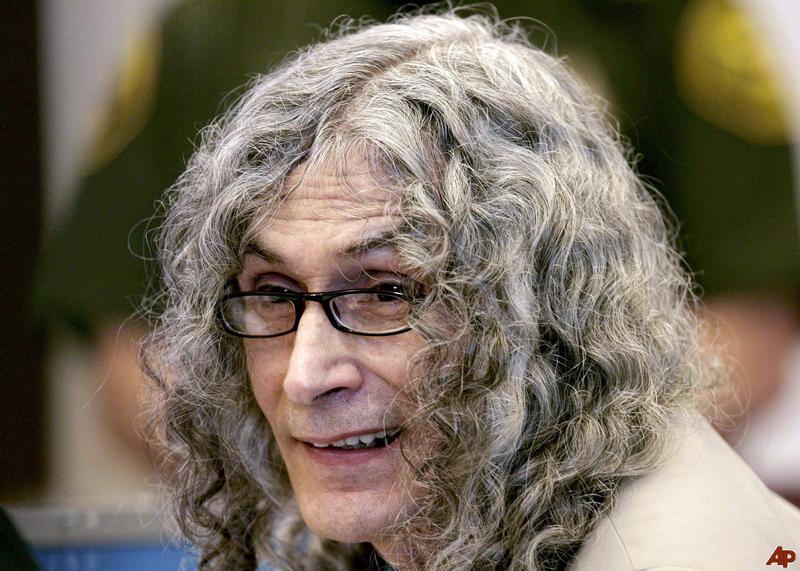

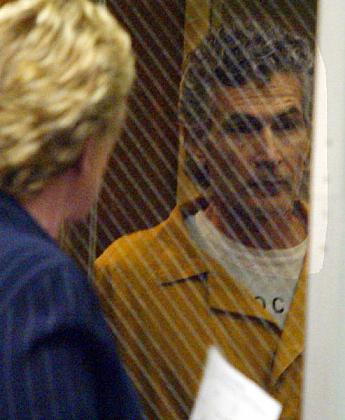

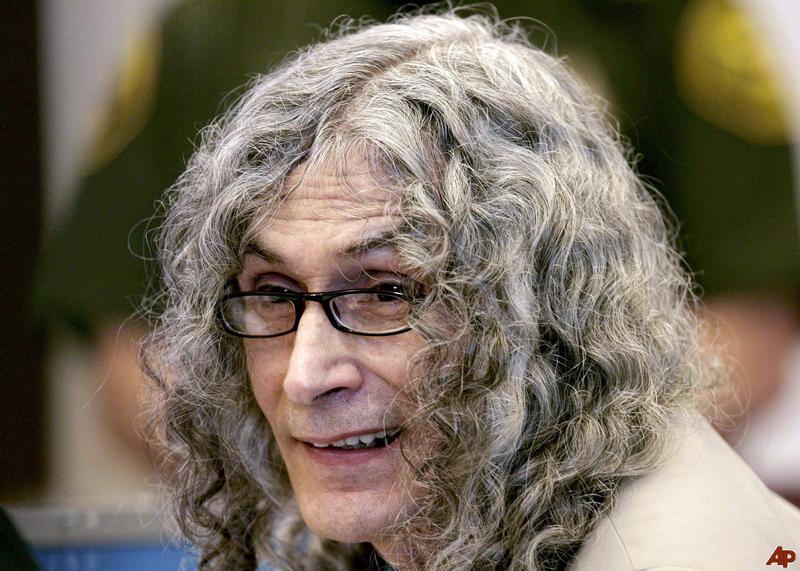

This Jan. 11, 2010 file photo shows Rodney Alcala, a former death row inmate who was twice convicted

of the 1979 killing of a 12-year-old Huntington Beach girl, sitting in Orange County Superior

Court in Santa Ana, Calif.

Serial Killer Rodney Alcala received multiple guilty verdicts for brutally raping torture and killing

several women in the late 1970's and early 1980's. February 25, 2010.

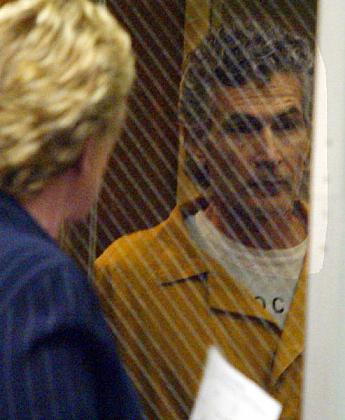

Serial killer Rodney Alcala talks with his investigator, Alfredo Rasch, in court in Santa Ana on March 30, 2010,

before being sentenced to death. In February, Alcala was found guilty of kidnapping and murdering

12-year-old Robin Samsoe of Huntington Beach, plus the murder of four women in Los Angeles County

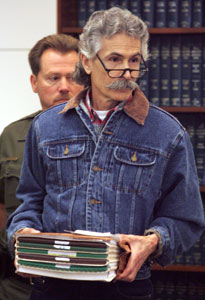

Serial killer Rodney Alcala listens as he is sentenced to death by Judge Francisco Briseno

in a Santa Ana courtroom.

Background information

Birth name Rodrigo Jacques Alcala-Buquor

Also known as Dating Game Killer

John Berger

John Burger

Rod Alcala

Born (1943-08-23) August 23, 1943 (age 69)

San Antonio, Texas, U.S.

Conviction Battery, kidnapping, murder, probation violation, providing cannabis to a minor, rape

Sentence Death

Killings

Number of victims 8–130

Country United States

State(s) California, possibly New York, possibly Washington

Date apprehended July 24, 1979

Classification: Serial killer

Characteristics: Rape

Number of victims: 5 - 100 +

Date of murders: 1977 - 1979

Date of arrest: July 27, 1979

Date of birth: August 23, 1943

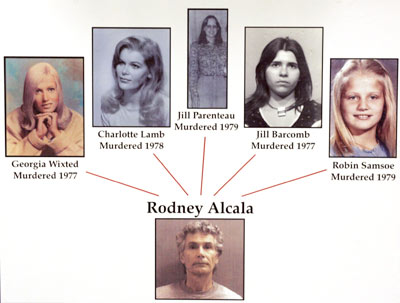

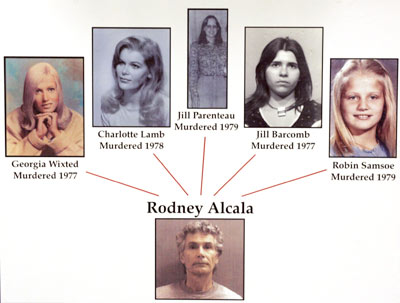

Victims profile: Robin Samsoe, 12 /Jill Barcomb, 18 / Georgia Wixted, 27 / Charlotte Lamb, 32 / Jill Parenteau, 21

Method of murder: Beating / Strangulation

Location: California, USA

Status: Sentenced to death March 30, 2010

Rodney James Alcala (born Rodrigo Jacques Alcala Buquor; August 23, 1943) is a convicted rapist and serial killer. He was sentenced to death in California in 2010 for five murders committed in that state between 1977 and 1979, and is under indictment for two additional homicides in New York. His true victim total remains unknown, and could be much higher. Prosecutors say that Alcala "toyed" with his victims, strangling them until they lost consciousness, then waiting until they revived, sometimes repeating this process several times before finally killing them.

He is sometimes labeled the "Dating Game Killer" because of his 1978 appearance on the television show The Dating Game in the midst of his murder spree. Police discovered a collection of more than 1,000 photographs taken by Alcala, mostly of women and teenaged boys, most of them in sexually explicit poses. They speculate that some of his photographic subjects could be additional victims.

One police detective called Alcala "a killing machine" and others have compared him to Ted Bundy. A homicide investigator familiar with the evidence speculates that he could have murdered as many as 50 women, while other estimates have run as high as 130.

Early life

Alcala was born Rodrigo Jacques Alcala Buquor in San Antonio, Texas to Raoul Alcala Buquor and Anna Maria Gutierrez. His father abandoned the family and his mother moved Rodney and his sisters to suburban Los Angeles when Alcala was about 12.

He joined the United States Army in 1960, at age 17, where he served as a clerk. In 1964, after what was described as a "nervous breakdown", he was diagnosed with antisocial personality disorder by a military psychiatrist and discharged on medical grounds. Other diagnoses later proposed by various psychiatric experts at his trials included narcissistic personality disorder and borderline personality disorder. Homicide and forensic expert Vernon Geberth described Alcala as having "malignant narcissistic personality disorder with the following co-morbities: psychopathy and sexual sadism"

Education

Alcala, who claims to have a "genius-level" IQ, graduated from the UCLA School of Fine Arts after his medical discharge from the Army, and later attended New York University using the alias "John Berger", where he studied film under Roman Polanski.

Early criminal history

Alcala committed his first known crime in 1968: A motorist in Los Angeles witnessed him luring an eight-year-old girl named Tali Shapiro into his Hollywood apartment and called police. The girl was found in the apartment raped and beaten with a steel bar, but Alcala escaped. He fled to the east coast and enrolled in the NYU film school using the name "John Berger". During the summer months he also obtained a counseling job at a New Hampshire arts camp for children, using a slightly different alias, "John Burger."

In June 1971, Cornelia Michel Crilley, a 23-year-old Trans World Airlines flight attendant, was found raped and strangled in her Manhattan apartment. Her murder would remain unsolved for the next 40 years.

Later that summer, two children at the New Hampshire arts camp noticed Alcala's FBI wanted poster at the post office and notified camp directors. He was arrested and extradited back to California. By then, however, Tali Shapiro's parents had relocated her and her family to Mexico and refused to allow her to testify at Alcala's trial. Unable to convict him of rape and attempted murder without their primary witness, prosecutors were forced to permit Alcala to plead guilty to a lesser charge of assault. He was paroled after 34 months, in 1974, under the "indeterminate sentencing" program popular at the time, which allowed parole boards to release offenders as soon as they demonstrated evidence of "rehabilitation." Less than two months later, he was arrested after assaulting a 13-year-old girl known in court records as "Julie J.", who had accepted what she thought would be a ride to school. Once again, he was paroled after serving two years of an "indeterminate sentence."

In 1977, after his second release from prison, Alcala's Los Angeles parole officer permitted him to travel to New York City. NYPD cold-case investigators now believe that one week after arriving in Manhattan, Alcala killed Ellen Jane Hover, 23, daughter of the owner of Ciro’s, a popular Hollywood nightclub, and goddaughter of Dean Martin and Sammy Davis, Jr. Her remains were found buried on the grounds of the Rockefeller Estate in Westchester County.

In 1978 Alcala worked for a short time at the Los Angeles Times as a typesetter, and was interviewed by members of the Hillside Strangler task force as part of their investigation of known sex offenders. Although Alcala was ruled out as the Hillside Strangler, he was arrested and served a brief sentence for marijuana possession.

During this period Alcala also convinced hundreds of young men and women that he was a professional fashion photographer, and photographed them for his "portfolio." A Times co-worker later recalled that Alcala shared his photos with workmates. "I thought it was weird, but I was young, I didn’t know anything," she said. "When I asked why he took the photos, he said their moms asked him to. I remember the girls were naked.” Most of the photos are sexually explicit, and most remain unidentified. Police fear that some of the subjects may be additional cold-case victims.

Samsoe murder and first two trials

Robin Samsoe, a 12-year-old girl from Huntington Beach, California disappeared somewhere between the beach and her ballet class on June 20, 1979. Her decomposing body was found 12 days later in the foothills of Los Angeles. Police subsequently found her earrings in a Seattle locker rented by Alcala.

In 1980 Alcala was tried, convicted, and sentenced to death for Samsoe's murder, but his conviction was overturned by the California Supreme Court because jurors had been improperly informed of his prior sex crimes. In 1986, after a second trial virtually identical to the first except for omission of the prior criminal record testimony, he was convicted once again, and again sentenced to death. However, a Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals panel overthrew the second conviction, in part because a witness was not allowed to support Alcala's contention that the park ranger who found Samsoe's body had been "hypnotized by police investigators."

Additional victims discovered

While preparing their third prosecution in 2003, Orange County investigators learned that Alcala's DNA, sampled under a new state law (over his objections), matched semen left at the rape-murder scenes of two women in Los Angeles. Another pair of earrings found in Alcala's storage locker matched the DNA of one of the two victims. Additional evidence, including another cold-case DNA match in 2004, led to Alcala's indictment for the murders of four additional women: Jill Barcomb, 18, a New York runaway found "rolled up like a ball" in a Los Angeles ravine in 1977, and originally thought to have been a victim of the Hillside Strangler; Georgia Wixted, 27, bludgeoned in her Malibu apartment in 1977; Charlotte Lamb, 31, raped and strangled in the laundry room of her El Segundo apartment complex in 1978; and Jill Parenteau, 21, killed in her Burbank apartment in 1979. All of the bodies were found "posed...in carefully chosen positions."

Third (joined) trial

In 2003, prosecutors entered a motion to join the Samsoe charges with those of the four newly discovered victims. Alcala's attorneys contested it; as one of them explained, "If you’re a juror and you hear one murder case, you may be able to have reasonable doubt. But it’s very hard to say you have reasonable doubt on all five, especially when four of the five aren’t alleged by eyewitnesses but are proven by DNA matches. In 2006, the California Supreme Court ruled in the prosecution's favor, and in February 2010 Alcala stood trial on the five joined charges.

For the third trial Alcala elected to act as his own attorney. He took the stand in his own defense, and for five hours played the roles of both interrogator and witness, asking himself questions (addressing himself as "Mr. Alcala" in a deeper-than-normal voice), and then answering them. During this bizarre self-questioning and answering session he told jurors, often in a rambling monotone, that he was at Knott's Berry Farm when Samsoe was kidnapped. He also claimed that the earrings found in his Seattle locker were his, not Samsoe's. As "proof" he showed the jury a portion of his 1978 appearance on The Dating Game, during which his earrings — if he wore any — were obscured by his shoulder-length hair. He made no significant effort to dispute the other four charges. As part of his closing argument, he played the portion of Arlo Guthrie's song "Alice's Restaurant" in which the protagonist tells a psychiatrist he wants to "kill."

After less than two days' deliberation the jury convicted Alcala on all five counts of first-degree murder. A surprise witness during the penalty phase of the trial was Tali Shapiro, Alcala's first known victim. In March 2010, he was sentenced to death for a third time.

Dating Game appearance

In 1978 Alcala, despite his status as a convicted rapist and registered sex offender, was accepted as a contestant on The Dating Game. By then he had already killed at least two women in California and probably two others in New York. Host Jim Lange introduced him as "...a successful photographer who got his start when his father found him in the darkroom at the age of 13, fully developed. Between takes you might find him skydiving or motorcycling."

Actor Jed Mills, who competed against Alcala as "Bachelor #2", later described him as a "very strange guy" with "bizarre opinions". He added that Alcala did not wear earrings on the show, as he claimed during his 2010 trial; earrings were not yet a socially acceptable accoutrement for men in 1978. "I had never seen a man with an earring in his ear," he said. "I would have noticed them on him." The third contestant, Armand Chiami, has not made any public comments.

Alcala won a date with "bachelorette" Cheryl Bradshaw, who subsequently refused to go out with him, according to published reports, because she found him "creepy". Criminal profiler Pat Brown, noting that Alcala killed Robin Samsoe and at least two other women after his Dating Game appearance, speculated that Bradshaw's rejection might have been an exacerbating factor. "One wonders what that did in his mind," Brown said. "That is something he would not take too well. [Serial killers] don't understand the rejection. They think that something is wrong with that girl: 'She played me. She played hard to get.'"

Appeal status and additional charges

San Quentin State Prison, where Alcala was incarcerated from 1979 until his extradition to New York in 2012Alcala has been incarcerated since his 1979 arrest for Samsoe's murder. In the period between his second and third trial he wrote You, the Jury, a self-published 1994 book in which he asserted his innocence in the Samsoe case and suggested a different suspect. He also filed two lawsuits against the California penal system for a slip-and-fall claim, and for failing to provide him a low-fat diet.

New York

After his 2010 conviction New York authorities announced that they would no longer pursue Alcala because of his status as a prisoner awaiting execution. Nevertheless, in January 2011 a Manhattan grand jury indicted him for the murders of Ellen Hover, the Ciro's heiress, and Cornelia Crilley, the TWA flight attendant. Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance indicated that he intended to extradite Alcala and prosecute him for the two homicides in New York. New York's death penalty statute was ruled unconstitutional by the state's supreme court in 2004.

In June 2012 Alcala was extradited to New York where he pled not guilty to the Hover and Crilley homicides, and was ordered held without bail. A trial date of October 30 was set.

San Francisco

In March 2011, investigators in Marin County, north of San Francisco, announced that they were "confident" that Alcala was responsible for the 1977 murder of 19-year-old Pamela Jean Lambson, who disappeared after making a trip to Fisherman's Wharf to meet a man who had offered to photograph her. Her battered, naked body was subsequently found in Marin County near a hiking trail. With no fingerprints or usable DNA, charges are unlikely to be filed, but police claimed that there is sufficient evidence to convince them that Alcala committed the crime.

Washington

An investigation is underway in Seattle regarding Alcala's possible connection with the murders of Antoinette Wittaker, 13, in July 1977 and Joyce Gaunt, 17, in February 1978. In 1979 Alcala rented the Seattle-area locker where investigators eventually found jewelry belonging to two of his California victims.

Unidentified photographs

In March 2010, the Huntington Beach and New York City Police Departments released 120 of Alcala's photographs and sought the public's help in identifying them, in the hope of determining if any of the women and children he photographed were additional victims. Approximately 900 additional photos could not be made public, police said, because they were too sexually explicit. In the first few weeks, police reported that approximately 21 women had come forward to identify themselves, and "at least 6 families" said they believed they recognized loved ones who "disappeared years ago and were never found." However, according to one published account, as of November 2010 none of the photos had been unequivocally connected to a missing person’s case or an unsolved murder.

As of March 2011 the original 120 photos remain posted online, and police continue to solicit the public's help with further identifications.

Rodney James Alcala (born August 23, 1943) is a convicted rapist and serial killer who was sentenced to death in California in 2010 for five murders committed between 1977 and 1979, and is thought to be responsible for others.

He is sometimes labeled the "Dating Game Killer" due to his 1978 appearance on the American television show The Dating Game in the very midst of his murder spree.

Alcala is also notable for exceptional demonstrations of cruelty: Prosecutors say he "toyed" with his victims, strangling them until they lost consciousness, then waiting until they revived, sometimes repeating this process several times before finally killing them.

Investigators have found a collection of hundreds of photos of women and teenaged boys photographed by Alcala, and speculate that he could be responsible for many more murders in California. He is also a suspect in at least two unsolved murders in New York. Authorities have compared him to Ted Bundy, and fear that, as evidence continues to mount, he may prove to be one of the most prolific serial killers in American history.

Early life

Alcala was born Rodrigo Jacques Alcala-Buquor in San Antonio, Texas to Raoul Alcala Buquor and Anna Maria Gutierrez. He and his sisters were raised by his mother in suburban Los Angeles. His father abandoned the family.

He joined the United States Army in 1960, where he served as a clerk. In 1964, after what was described as a "nervous breakdown", he was diagnosed with antisocial personality disorder by a military psychiatrist and discharged on medical grounds.

Education

Alcala, who claims to have a "genius-level" IQ, graduated from the UCLA School of Fine Arts after his medical discharge from the Army, and later attended New York University using the alias "John Berger", where he studied film under Roman Polanski.

Early criminal history

Alcala committed his first known crime in 1968: A motorist in Los Angeles witnessed him luring an eight-year-old girl named Tali Shapiro into his Hollywood apartment and called police. The girl was found in the apartment raped and beaten with a steel bar, but Alcala escaped. He fled to the east coast and enrolled in the NYU film school using the name "John Berger." During the summer months he also obtained a counseling job at a New Hampshire arts camp for children, using a slightly different alias, "John Burger."

In 1971, after two campers noticed Alcala's FBI wanted poster at the post office and notified camp directors, he was arrested and extradited back to California. By then, however, Tali Shapiro's parents had relocated her family to Mexico, and refused to allow her to testify at Alcala's trial. Unable to convict him of rape and attempted murder without their primary witness, prosecutors were forced to permit Alcala to plead guilty to a lesser charge.

He was paroled after 34 months, in 1974, under the "indeterminate sentencing" program popular at the time, which allowed parole boards to release offenders as soon as they demonstrated evidence of "rehabilitation."

Less than two months later, Alcala was arrested for violating parole and providing marijuana to a 13-year old girl who claimed she had been kidnapped. Once again, he was paroled after serving two years of an "indeterminate sentence."

In 1977, despite his criminal record and official registration as a sex offender, he was hired as a typesetter by the Los Angeles Times in the midst of their coverage of the Hillside Strangler murders.

During this period Alcala also convinced dozens of young women that he was a professional fashion photographer, and photographed them for his "portfolio." Most of those photos remain unidentified, and police fear that some of the women may be additional victims (see below).

Samsoe murder and trials

Robin Samsoe, a 12-year-old girl from Huntington Beach, California disappeared somewhere between the beach and her ballet class on June 20, 1979. Her decomposing body was found 12 days later in the foothills of Los Angeles. Police subsequently found her earrings in a Seattle locker rented by Alcala.

In 1980 Alcala was tried, convicted, and sentenced to death for Samsoe's murder, but his conviction was overturned by the California Supreme Court because the Orange County Superior Court trial judge had allowed the jury to hear about the Tali Shapiro case, and Alcala's other rape and kidnapping convictions.

In 1986 he was convicted for a second time and again sentenced to death, but a Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals panel overthrew his conviction once again, in part because a witness was not allowed to support Alcala's contention that the park ranger who found Samsoe's body had been "hypnotized by police investigators."

Third (joined) trial

While preparing their third prosecution in 2003, Orange County investigators learned that Alcala's DNA, sampled under a new state law (over his objections), matched semen left at the rape-murder scenes of two women in Los Angeles. Another pair of earrings found in Alcala's storage locker matched the DNA of one of the two victims.

Additional evidence, including another cold case DNA match in 2004, led to Alcala's indictment for the murders of four additional women: Jill Barcomb, 18, killed in 1977 and originally thought to have been a victim of the Hillside Strangler; Georgia Wixted, 27, bludgeoned in her Malibu apartment in 1977; Charlotte Lamb, 31, raped and strangled in El Segundo in 1978; and Jill Parenteau, 21, killed in her Burbank apartment in 1979.

In 2003, prosecutors entered a motion to join the Samsoe charges with those of the four newly-discovered victims. Alcala contested the motion. In 2006, the California Supreme Court ruled in the prosecution's favor, and in 2009 Alcala stood trial once again. At the third trial Alcala, acting as his own attorney, told jurors, often in a rambling monotone, that he was at Knott's Berry Farm when Samsoe was kidnapped. (He offered no defense of any kind in the other four cases.)

As part of his closing argument, he played the portion of Arlo Guthrie's song "Alice's Restaurant" in which the protagonist tells a psychiatrist he wants to "kill." He was convicted on all five counts. A surprise witness during the penalty phase of the trial was Tali Shapiro, Alcala's first known victim. In March 2010, Alcala was sentenced to death for a third time.

Dating Game appearance

In 1978, Alcala — who had by then already killed at least two women — was accepted as a contestant on The Dating Game, despite being a convicted rapist and registered sex offender. Host Jim Lange introduced him as "...a successful photographer who got his start when his father found him in the darkroom at the age of 13, fully developed. Between takes you might find him skydiving or motorcycling." He won a date with "bachelorette" Cheryl Bradshaw, who subsequently refused to go out with him, according to published reports, because she found him "creepy." Jed Mills, an actor who sat next to Alcala onstage as "Bachelor #2", later described him as a "very strange guy" with "bizarre opinions." (The third contestant, Armand Chiami, has not publicly commented.)

Criminal profiler Pat Brown, noting that Alcala killed Robin Samsoe and at least two other women after his Dating Game appearance, speculated that Bradshaw's rejection might have been an exacerbating factor. "One wonders what that did in his mind," Brown said. "That is something he would not take too well. [Serial killers] don't understand the rejection. They think that something is wrong with that girl: 'She played me. She played hard to get.'"

Current status

Alcala has been incarcerated since his 1979 arrest for Samsoe's murder. While in prison he has written You, the Jury, a 1994 book in which he asserts his innocence in the Samsoe case and points to a different suspect. He has also filed two lawsuits against the California penal system for a slip-and-fall claim, and for failing to provide him a low-fat diet.

New York officials have the option of filing additional charges against Alcala, who is the main suspect in the case of Ciro's Nightclub heiress Ellen Jane Hover, murdered in 1977 while Alcala was working in New York as a security guard. He is also suspected in the murder of TWA flight attendant Cornelia "Michael" Crilley, which occurred in 1971 while Alcala was enrolled at NYU.

Alcala continues to maintain his innocence, and currently remains on death row at San Quentin State Prison.

Unidentified photographs

In April 2010, the Huntington Beach Police Department made public 120 of Alcala's photographs in an effort to identify some of the women and determine if any could be additional victims. Anyone willing to provide information about any of the photos was asked to call Det. Patrick Ellis at (714) 536-5971.

In the first few weeks, approximately 20 women had come forward to identify themselves.

Aliases

Rodney Alcala (legal name)

Rod Alcala

John Berger

John Burger

Timeline

year of event

Event, victim name

indicates date of crime

Offense; offender status

/Location

Alias/Note

1961-64

US Army

1968

Graduated from UCLA

1968

Tali Shapiro, age 8 Rape, Battery; Pleaded guilty to assault, 1971/California

1968-71

Fugitive

1968–71

Enrolled at NYU Film School New York, NY John Berger

1970-71

Camp Counselor New Hampshire John Burger

1971

Cornelia Crilley, age 23 Murder; Suspected/New York

1971

FBI Ten Most Wanted List

1971–74

Incarcerated (Tali Shapiro conviction) California

1974

"Julie J.", age 13 Parole Violation, providing marijuana to minor; Convicted, 1974/California

1974-78

Ted Bundy Colorado/Florida/Idaho/

Oregon/Utah, etc. for time-line comparison

1974-77

Incarcerated ("Julie J." conviction) California

1975-77

Son of Sam aka David Berkowitz New York City for time-line comparison

1977

Ellen Hover Murder; Suspected/New York John Berger

1977

Worked as Los Angeles Times typesetter California

1977-78

Hillside Strangler California for time-line comparison

1977

Jill Barcomb, age 18 Murder; Convicted, 2009/California

1977

Questioned by FBI regarding Hover California Rodney Alcala, John Berger

1977

Georgia Wixted, age 27 Murder; Convicted, 2009/California

1978

interviewed as part of Hillside Strangler investigation California

1978

Incarcerated (Possession-drugs) California

1978

Contestant, The Dating Game California

1978

Charlotte Lamb, age 32 Murder; Convicted, 2009/California

1979

Jill Parenteau, age 21 Murder; Convicted, 2009/California

1979

Robin Samsoe age 12 Murder; Convicted, 1980, 1986, 2009/California

1979

Arrested on suspicion of Samsoe murder California

1980

Conviction #1, sentenced to death for Samsoe murder California

1984

Conviction #1 overturned by California Supreme Court California

1986

Conviction #2, sentenced to death for Samsoe murder California

1994

You, the Jury "True crime" book, asserting his innocence

2001

Conviction #2 overturned by 9th US Circuit Court of Appeals California

2003

DNA collected, 4 additional murders discovered California

2003

Motion to join Samsoe case with 4 others proposed; contested by Alcala California

2006

Case join granted by California Supreme Court California

2009-10

Conviction #3, sentenced to death for murders of Samsoe, Parenteau, Lamb, Wixted, and Barcomb California

Serial killer Rodney Alcala sentenced to death

By Paloma Esquivel - Los Angeles Times

March 30, 2010

An Orange County judge on Tuesday sentenced serial killer Rodney Alcala to death for five killings in the 1970s, marking yet another turn in a three-decade-long legal drama.

Judge Francisco Briseno's decision came several weeks after a jury recommended the death penalty for Alcala after convicting him on charges of slaying four women and a teenage girl.

Briseno said photos of the women taken by Alcala show he had "sadistic sexual motives" and that "some of the victims were posed after death." The judge said Alcala had an "abnormal interest in young girls."

It was the third time that Alcala, 66, had been convicted for the murder of Robin Samsoe, 12, last seen riding her bike to ballet class in June 1979. He had been condemned to death both times, but the convictions were overturned. He has been in custody since his 1979 arrest.

Before the third trial began in January, he was linked through DNA, blood and fingerprint evidence to the deaths of Jill Barcomb, 18, whose body was found in the Hollywood Hills; Georgia Wixted, 27, of Malibu; Charlotte Lamb, 32, of Santa Monica; and Jill Parenteau, 21, of Burbank.

During his closing arguments earlier this month, Alcala -- a onetime photographer and “Dating Game” contestant who acted as his own attorney in this trial -- asked jurors to spare him from the death penalty, saying they would become killers themselves if they sent him to death row and arguing that the sentence would lead to decades of appeals.

A sentence of life in prison without parole "would end this matter now," he said.

Alcala: The long road to justice

By Kimi Yoshino

1972 — Alcala is convicted in the 1968 rape and beating of an 8-year-old girl.

Nov. 10, 1977 — The body of 18-year-old Jill Barcomb is found in the Hollywood Hills. She had been sexually assaulted, bludgeoned and strangled with a pair of blue pants.

Dec. 16, 1977 — Georgia Wixted, 27, is found beaten to death at her home in Malibu. She had been sexually assaulted and strangled.

1978 — Alcala appears in an episode of “The Dating Game” as Bachelor No. 1

June 24, 1978 — Charlotte Lamb, a 32-year-old legal secretary from Santa Monica, is found in the laundry room of an El Segundo apartment complex. She had been sexually assaulted and strangled with a shoelace.

June 14, 1979 — Jill Parenteau, 21, is found strangled on the floor of her Burbank apartment.

June 20, 1979 – Robin Samsoe, 12, disappears near the Huntington Beach Pier. Her body is found 12 days later in the Sierra Madre foothills.

July 24, 1979 — Rodney James Alcala, an unemployed photographer, is arrested at his parents’ Monterey Park home.

September 1980 – Alcala is convicted of the 1978 rape of a 15-year-old Riverside girl and sentenced to nine years in state prison.

June 20, 1980 — Orange County Superior Court Judge Philip E. Schwab sentences Alcala to death after he is convicted of Samsoe's murder.

July 11, 1980 — The Los Angeles County district attorney’s office files murder, burglary and sexual assault charges against Alcala in the slaying of Parenteau.

April 15, 1981 — The L.A. County district attorney’s office tells a judge that prosecution of Alcala in the Parenteau case could not proceed because a key witness admitted that he had committed perjury in another case.

Aug. 23, 1984 — The state Supreme Court reversed Alcala’s murder conviction in connection with Samsoe, ruling that the jury was improperly told about Alcala’s prior sex crimes.

June 20, 1986 — For the second time, Alcala is convicted of Samsoe’s murder and sentenced to death in Orange County Superior Court.

Dec. 31, 1992 — The California Supreme Court unanimously upholds Alcala’s death sentence.

April 2, 2001 — A federal appellate court overturns Alcala’s death sentence in the Samsoe case, ruling that the Superior Court judge precluded the defense from presenting evidence “material to significant issues.”

June 5, 2003 — The Los Angeles County district attorney’s office files murder charges against Alcala alleging that he killed Wixted during a burglary and rape.

Sept. 19, 2005 — Additional murder charges are filed against Alcala in connection to the deaths of Barcomb, Wixted and Lamb.

Jan. 11, 2010 — Alcala’s trial for the five murders begins. He represents himself.

March 9, 2010 — Alcala is again sentenced to death.

The 'most prolific' serial killer in U.S. history is sentenced to death as police fear he could be behind 130 murders

By David Gardner - DailyMail.co.uk

1st April 2010

Police have released more than 100 photographs of unidentified women and girls amid fears they could be the victims of America's worst ever serial killer.

The pictures were taken by Rodney Alcala, who was sentenced to death by lethal injection for the savage murders of a 12-year-old girl and four women.

However, the 66-year-old has admitted killing another 30 women in the 1970s and police believe there could be many more victims.

They have already linked him to the deaths of two Seattle teenagers aged 13 and 17, and a 19-year-old who vanished from the same area, as well as two women in New York and several more in Los Angeles.

The photos were discovered hidden in a storage locker in Seattle, Washington, where Alcala, an amateur photographer, kept his possessions before his arrest.

Although many of the 1,000 pictures were innocent poses in a park or on the beach, some women had stripped off for the camera.

Police believe that Alcala - who is known in the U.S. as the Dating Game Killer because he once appeared on America's version of Blind Date - kept the photographs as sick souvenirs of his victims.

The women in the photos range in age from schoolgirls to women in their 20s and 30s, and are believed to come from across the U.S. Two of the pictures may have been taken after the women were murdered.

Prosecutor Matt Murphy said: 'We'd like to locate the women in these pictures. Did they simply pose for a serial killer or did they become victims of his sadistic, murderous pattern?

'He committed unspeakable acts of horror. He gets off on the infliction of pain on other people. He's an evil monster who knows what he is doing is wrong and doesn't care.'

Detective Claiff Shepard said: 'He's right up somewhere below Hitler and right around Ted Bundy. It is not humane what he does to these victims. It is tortuous.'

Alcala - who defended himself during his trial - preyed on women and girls by offering to take their photographs.

He then raped his victims, strangled them until they were unconscious before reviving them and killing them.

The photographer, who is said to have a genius IQ of 160, often boasted of his winning an episode of the American version of Blind Date.

However, the woman who chose him later cancelled their date because she found him 'too creepy'.

Alcala appeared unconcerned about his fate on Tuesday, when he was given the death sentence for kidnapping and murdering 12-year-old Robin Samsoe, who disappeared after leaving home for ballet class on her bicycle in 1979.

He laughed and talked throughout the trial at Orange County Superior Court, even after also being convicted of murdering four Los Angeles women - Georgia Wixted, 27, Jill Barcomb, 18, Charlotte Lamb, 32, and Jill Parenteau, 21 - between 1977 and 1979.

It took nearly 30 years for the law to catch up with him. He was previously convicted twice of killing Robin, but the verdicts were overturned. An earring that belonged to the little girl was also found with the photo cache.

America's most prolific serial killer is often considered to be Henry Lee Lucas, who was convicted of four murders in the late 1970s although police believe he may have been responsible for more than 200.

After his imprisonment, Lucas confessed to 600 killings although he later claimed he had lied to become famous.

Ted Bundy is believed to have raped and murdered 35 women between 1973 and 1978, although police believe there are many more victims. He was executed in 1989 by electric chair for his last murder in Florida.

Calif. Man Convicted of 5 Serial Slayings

Rodney Alcala Found Guilty of Murdering 4 Women, 12-Year-Old Girl in Late 1970s

CBSNews.com

Feb. 25, 2010

A jury convicted a Southern California man Thursday of murdering four women and a 12-year-old girl in the late 1970s.

Jurors took less than two days to reach guilty verdicts against Rodney Alcala after six weeks of testimony. He could face a death sentence when the penalty phase of the case begins Tuesday.

The 66-year-old Alcala, who acted as his own lawyer, had previously been sentenced to death twice for the murder of 12-year-old Robin Samsoe of Orange County, but both convictions were overturned.

Prosecutors added the murders of four women in 2006 after investigators discovered DNA and other forensic evidence linking him to those cases.

The jury heard grueling testimony that two of the four adult victims were posed nude and possibly photographed after their deaths; one was raped with a claw hammer; and all of them were repeatedly strangled and resuscitated during their deaths to prolong their agony.

Prosecutors also alleged Alcala, an amateur photographer, took earrings from at least two of the victims as trophies and carried one 18-year-old to a remote canyon road where he raped and sodomized her before bashing her head with a rock.

At trial, Orange County prosecutor Matt Murphy told jurors DNA found in the bodies of three of the women proved Alcala had committed those murders. Witnesses said Alcala and the fourth woman were seen in the same club on the night she was killed.

The Samsoe case, which was first tried in 1980, presented more of a challenge for prosecutors because it was built largely on circumstantial evidence.

The young girl's body was found in Angeles National Forest 12 days after she disappeared.

No one saw the blond-haired girl being abducted on June 20, 1979 as she rode her friend's bike to ballet class. In addition, investigators were unable to recover forensic evidence because of the condition of her remains.

The current trial focused almost entirely on evidence in the Samsoe case, with Alcala choosing not to testify about the murders of the four adult women when he took the stand in his own defense.

Prosecutors relied on witnesses who testified about seeing a curly haired photographer taking pictures of Samsoe, her friend and other teenagers on the beach minutes before Samsoe disappeared. Photos of one of the girls were later found in Alcala's possession.

Also key to the trial was a pair of gold ball earrings that Samsoe's mother said belonged to her daughter.

The earrings were found in a jewelry pouch in a storage locker that Alcala had rented in Seattle, where he was arrested a month after her murder.

Investigators found other earrings in the same pouch, including a small rose-shaped stud that contained a trace of DNA from another of Alcala's alleged victims, Charlotte Lamb.

Alcala maintained, however, that the gold ball earrings were his and introduced as evidence a video of himself as the winning contestant on a 1978 episode of "The Dating Game." He told jurors the seconds-long, grainy clip from the video showed him wearing the gold earrings a year before Samsoe was killed.

In his closing argument, Alcala accused prosecutors of lumping the four Los Angeles women in with Samsoe to inflame the jury. He also pointed out inconsistencies in the case and lapses in witnesses' recollections of that day.

Alcala noted that one witness who saw him on the beach said he was dark-skinned and 175 pounds when Alcala is light-skinned and weighs 150 pounds.

Two other witnesses disagreed on the clothing he was wearing. An initial police bulletin said the suspect in the Samsoe case was balding, but Alcala pointed out he has as full head of long, curly hair.

The other women murdered were Georgia Wixted, 27, of Malibu; Charlotte Lamb, 32, of Santa Monica; Jill Parenteau, 21, of Burbank; and Jill Barcomb, 18, who had just moved to Los Angeles from Oneida, N.Y.

State Supreme Court takes on notorious 1979 O.C. murder case

High court to decide if prosecutors can try Rodney Alcala for 4 old L.A. murders along with kidnapping and murder of H.B. girl.

By Larry Welborn - The Orange County Register

Wednesday, April 2, 2008

SANTA ANA – Former death row inmate Rodney James Alcala has twice been put on trial for killing a 12-year-old Huntington Beach girl in one of Orange County's most notorious murder cases.

Twice he's been convicted. Twice he's been sentenced to death. And twice his convictions and sentences for killing Robin Samsoe in 1979 were reversed on appeal.

He's back in the Orange County court system for round three of People v. Alcala.

But his court-appointed defense attorneys are arguing that the now-65-year-old defendant can not get a fair trial in Orange County because prosecutors want to try Alcala for four additional murders at the same time. They say that would overwhelm the defense with a mountain of evidence.

They claim in documents filed in Superior Court, the 4th District Court of Appeal and most recently the California Supreme Court that the Orange County District Attorney's Office is unfairly piling on Alcala.

Justices on the state's highest court – in a rare move – will hear arguments this afternoon during a session in Los Angeles.

Defense attorney Richard Schwartzberg isn't arguing that Alcala can't get a fair trial just because it is the third time around, but because Senior Deputy District Attorney Matt Murphy wants want to try Alcala for five murders instead of just one.

Murphy raised the stakes after an Orange County Grand Jury returned an indictment in 2005 accusing Alcala of strangling or beating four women in neighboring Los Angeles County nearly three decades ago.

Those cold cases allegedly link Alcala through DNA evidence to murder scenes in the 1970s, investigators contend. DNA evidence was not available during the 1970s.

Orange County can charge the Los Angeles County cases – prosecutors claim – because a 1998 law allows serial killers who commit murders in separate counties to be tried in one.

That law was prompted by the recognition that serial killers who go on brutal killing rampages do so without consideration of county lines, said Deputy District Attorney James Mulgrew, who is handling the motions part of the Alcala case.

Mulgrew also insists there is a legitimate interest in judicial economy and that there would be a reduction of inconvenience and trauma for witnesses and victim family members by having one trial with multiple murder counts rather that several trials on individual counts in multiple courtrooms.

But Alcala's court-appointed defense attorneys, Schwartzberg and George Peters are crying foul.

Schwartzberg contends that Alcala's first two trials in Orange County in the Samsoe case were close decisions for the juries, and that two separate appellate courts found sufficient errors in those trials to justify reversing the verdicts.

"Our focus is to fight the Samsoe case, and it always has been," Schwartzberg said Tuesday. "If a third jury hears he has potentially killed four other women, any doubt he killed Robin Samsoe will evaporate in a second."

Schwartzberg also disputes whether the evidence in the four Los Angeles cases would be admissible if Alcala stood trial again for the Samsoe murder alone.

In 2006, Orange County Superior Court Judge Francisco Briseno agreed with prosecutors, allowing all five slayings to be combined in one trial to be heard in Orange County.

But the 4th District Court of Appeal in Santa Ana later over-ruled Briseno, finding that adding all four murder cases to the Samsoe trial would be too much. The appellate court decided that Murphy can add two Los Angeles cases to the Orange County prosecution, but not all four.

That decision prompted both Schwartzberg and Mulgrew to appeal to the California Supreme Court: Schwartzberg wants the state's highest court to strike all four Los Angeles slayings from the Orange County prosecution, while Mulgrew wants the court to reinstate the two counts removed by the appellate court.

Both lawyers said Tuesday that it is rare for the state's high court to review any pre-conviction issue from a local county. Schwartzberg said it probably happens out of Orange County Superior Court only once every three or four years.

Accused Serial Killer Facing Third Trial Enters Plea

November 23, 2005

SANTA ANA, Calif. -- A man facing a third trial for the murder of a 12-year-old Huntington Beach girl in 1979 pleaded not guilty Tuesday to charges of murdering four Los Angeles-area women in the 1970s.

Rodney James Alcala, 62, has spent much of the last 20 years on death row in connection with the slaying of Robin Samsoe. His two previous convictions in the case were overturned, and a date for the third trial has not yet been set.

Alcala was indicted Sept. 9 for the murders of Jill Barcomb, 18; Georgia Wixted, 27; Charlotte Lamb, 32;, and Jill Parenteau, 21. The slayings occurred between late-1977 and mid-1979.

The women were sexually assaulted, then beaten or strangled.

The indictment also alleges the special circumstance allegations of torture, multiple murder, robbery, rape, burglary and oral copulation.

Los Angeles County prosecutors already have announced they will seek the death penalty against Alcala on the four new cases if he is convicted.

Alcala has been in Orange County since 2003 while awaiting a new trial in the Samsoe case.

Los Angeles County prosecutors want to combine the Los Angeles County cases with the Orange County case, using prosecutors from both district attorney offices.

Orange County Superior Court Judge Francisco Briseno set a hearing on Jan. 13 to determine if the cases can be combined and tried in Orange County.

Defense attorney Richard Schwartzberg told Briseno he will oppose consolidation.

Mindful that the appeals court has twice tossed out Alcala's convictions for the Samsoe killing, defense attorney George Peters later told reporters that consolidation is an attempt to shore up a weak case with new charges that could bias a jury.

Schwartzberg told Briseno that the statute allowing consolidation is new and that there is no settled case law regarding it. If the ruling goes against his client, Schwartzberg indicated he would appeal the ruling while trial is still pending.

Orange County District Attorney Tony Rackauckas told reporters earlier that "by consolidating the charges, we will be able to pool our resources and give the public a clearer understanding of who Mr. Alcala is and what he did."

Prosecutors also said it will allow for judicial economy and for overlapping evidence to be presented.

Briseno also signed an order giving prosecutors access to Alcala's dental records from San Quentin.

According to the motion submitted by Los Angeles Deputy District Attorney Gina Satriano, evidence of a bite mark was recovered from the body of Barcomb by the coroner in 1979 and prosecutors want to compare the evidence collected from the victim's body to Alcala's teeth impressions.

According to Satriano, the bite mark severed the victim's right breast nipple.

The records will be turned over to prosecutors on Dec. 16.

Samsoe disappeared near the Huntington Beach Pier in July 1979, and her remains were found 12 days later in the San Gabriel Mountain foothills.

Alcala was convicted in 1980 of murdering Samsoe. He won a second trial in 1984 when the California Supreme Court ruled that evidence of prior attacks against young girls should not have been allowed at trial.

Alcala served time for attacking an 8-year-old girl with a pipe in 1968, and completed another term for an attack on a 14-year-old girl.

In 1986, he was tried again and convicted in the Samsoe case, although a key prosecution witness -- a Forest Service firefighter who was among those who found the girl's body and later linked Alcala to the site -- did not testify again because she said she had amnesia.

A three-judge panel of the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals unanimously upheld a trial judge's order that Alcala should be retried or released.

The retrial had been delayed by the death of attorney David A. Zimmerman, who had represented Alcala on his first appeal of the case.

After Peters was appointed, Alcala was set to go to trial on Oct. 3 but that date was vacated with the addition of the new charges.

Satriano could not estimate when trial would begin on the case, saying a lot has to do with the consolidation motion.

California man accused in serial killings

September 20, 2005

LOS ANGELES - A California man who twice has had death sentences overturned for the 1979 murder of a 12-year-old girl has been indicted for strangling four Los Angeles area women in a serial killing spree, prosecutors said Monday.

Rodney James Alcala, who won new trials after both of his death sentences for the slaying of Robin Samsoe, was linked to four other unsolved murders from the 1970s through DNA and blood evidence, prosecutors said.

“Clearly the only punishment appropriate for Mr. Alcala is the death penalty, and we will pursue it again,” Orange County District Attorney Tony Rackauckas said at a joint press conference with Los Angeles prosecutors.

The indictment charges Alcala, a freelance photographer, with killing Jill Barcomb, 18, and Georgia Wixted, 27, in 1977, Charlotte Lamb, 32, in 1978 and Jill Parenteau, 21, in 1979. All four were beaten, sexually assaulted and strangled.

Prosecutors from both Los Angeles and Orange counties will work on the case and will try Alcala, 62, for all five murders together. He was in jail awaiting a retrial for Samsoe’s murder when the indictments came down.

Alcala, who has prior convictions for assault and served two years in prison for the 1968 kidnapping and rape of an 8-year-old girl, was in court briefly Monday for an arraignment but that hearing was postponed until Oct. 6.

Authorities believe Alcala used his above-average intelligence and charm in approaching girls to take their pictures. He once appeared on television’s “The Dating Game.”

Samsoe, an aspiring gymnast from Huntington Beach, Calif., vanished on June 20, 1979, while on her way to a ballet lesson. Her skeletal remains were found in a national forest some two weeks later.

Alcala, who was seen with a girl matching Samsoe’s description near the spot where her body was found, was convicted of her murder in 1980 and sentenced to die. The California Supreme Court later overturned the guilty verdict, saying jurors should not have been told about his prior convictions.

Although the forestry worker who saw Alcala near the scene of the crime developed amnesia and could not testify again, he was convicted a second time of murdering Samsoe. A federal judge overturned that conviction, citing concerns about his defense.

Defendant Is Now Called Serial Killer

Rodney Alcala, facing a second retrial in the abduction and death of an O.C. girl, allegedly killed four L.A. County women in the late 1970s.

By Claire Luna and Seema Mehta - Los Angeles Times

September 20, 2005

A man behind bars for the last 25 years for allegedly killing a 12-year-old Huntington Beach girl is now accused of slaying four women in Los Angeles County in the late 1970s during a serial-killing spree, officials said Monday.

Rodney James Alcala, 62, who is in Orange County jail awaiting his second retrial in the 1979 kidnapping and killing of Robin Samsoe, made a court appearance Monday on charges of sexually assaulting and murdering four women, who were strangled in or near their homes. His arraignment was postponed until Oct. 6.

After uncovering the new cases through DNA and blood evidence, detectives said they were trying to connect Alcala with other unsolved missing-person and murder cases, including two killings in New York state.

"He belongs right up there" in a list of serial killers, said Los Angeles Police Det. Cliff Shepard, who is in the department's cold-case unit. "Him being behind bars since 1979 probably saved a lot of lives."

The killings occurred in an era when Southern California was being terrorized by serial killers such as the Hillside Strangler and the Freeway Killer. At the time, police suspected that at least one of the women now linked to Alcala was a victim in the string of deaths attributed to the Hillside Strangler.

The new charges against Alcala involve four slayings from 1977 to 1979. Authorities said the victims died under similar circumstances.

The body of Jill Barcomb, 18, was found in the Hollywood Hills on Nov. 10, 1977, three weeks after she moved to California from Oneida, N.Y. She was sexually assaulted, bludgeoned and strangled with a pair of blue pants. Coroner's officials found three bite marks on her right breast.

The nude body of Centinela Hospital nurse Georgia Wixted, 27, was found Dec. 16, 1977, in her Malibu apartment. Wixted had been beaten, sexually assaulted and strangled. A hammer was found next to her body.

Legal secretary Charlotte Lamb, 32, of Santa Monica was found June 24, 1978, in the laundry room of an El Segundo apartment complex. She had been sexually assaulted and strangled with a shoelace.

On June 13, 1979 — a week before Robin Samsoe was abducted and killed — Jill Parenteau was found sexually assaulted and strangled in her Burbank apartment, pillows propping up her nude body. Law enforcement sources said Alcala allegedly met the 21-year-old keypunch operator at a restaurant.

Police in New York suspect Alcala killed at least two women there, one of them Ellen Hover, 24, in 1977. She was last seen in her New York apartment July 15, and her body was found 11 months later in a shallow grave on the Rockefeller estate, about 100 feet from where another woman told police she had posed for Alcala, an amateur photographer.

"Mr. Alcala left a trail of evil in multiple states and multiple counties," said Los Angeles Dist. Atty. Steve Cooley.

Orange County Dist. Atty. Tony Rackauckas said Alcala's arrest in Robin Samsoe's death was "the only reason he stopped killing."

Alcala refused a jailhouse interview and his attorney declined to discuss the new charges.

Authorities said Alcala met the women in discos and other public places, flirted with them and then followed them home when they spurned his advances.

"The reality is he was running around Southern California in the '70s looking for prey," said Los Angeles County Sheriff's Capt. Ray Peavy, head of the homicide bureau. "He looked for innocent victims who couldn't put up much of a fight and caught them when they were home in bed and pretty much defenseless."

The Los Angeles County cases had stalled for decades until they were cracked with the help of a statewide DNA database. In each of the slayings, the killer left semen or other biological material on the objects he used to strangle his victims.

After a recent state law required Alcala to provide a DNA sample to be used in crime-solving efforts, the state Department of Justice connected him a year ago to the unsolved killings.

"The DNA hits were like turning a light on in a room," Peavy said. "Suddenly an unsolvable case is now solved."

Sheriff's Det. Cheryl Comstock has been investigating the cases since the DNA links were found, Peavy said. She interviewed Alcala in prison several times and was able to confirm that he was not behind bars at the time of the killings.

Wixted's sister and brother-in-law, Anne and Al Michelena of Irvine, said Alcala's coming arraignment was a relief.

"I just regret that most of my family didn't live long enough to hear the news," particularly their mother, said Anne Michelena, 50, an elementary school teacher.

"For the past 25 years, I've been constantly looking over my shoulder, not knowing what I was looking for or who I was looking for. It got to the point where I thought I would never know," she added, but "I never stopped wondering."

She said the charges, coming after more than 25 years, should give hope to families in similar situations.

Her husband, who retired in August after 25 years of investigating killings and supervising the Los Angeles Police Department's robbery/homicide unit, had regularly checked the case's status with the Sheriff's Department.

He never knew Wixted — he met his future wife shortly after her sister's death. But seeing how the killing affected his wife, he said, shaped his interactions with victims he met through work.

Prosecutors hope to try all five cases, including the retrial in the Robin Samsoe killing, together in Orange County. Consolidating the cases will allow the counties to pool resources and shorten the survivors' already lengthy wait for justice, Rackauckas said.

Lawyers for Alcala said they would try to have the Orange County case tried separately from the others.

"That way, the jury can see that case in isolation and weigh it in isolation, without any information that would bias their view," said attorney George Peters outside court.

While Peters declined to discuss the new charges, he said his client has repeatedly insisted he did not kill the girl.

Robin, an aspiring gymnast, vanished June 20, 1979, as she bicycled to a dance lesson. Her body was found July 2 in the Angeles National Forest, in the foothills near Sierra Madre. Her body had decomposed to the point that police could not determine how she was killed or whether she had been sexually assaulted.

At the time, Alcala was an amateur photographer who had recently been a typist at the Los Angeles Times. A UCLA graduate, he had also worked for a time at a camp in New Hampshire, teaching filmmaking to children.

In 1979, while on parole for raping and beating an 8-year-old girl, Alcala appeared on "The Dating Game" television show. "It's pretty chilling to watch the banter between him and these contestants," Peavy said. "This is a serial killer, and here's a woman flirting with him."

At the time of Robin's death, he was awaiting trial on charges of raping and beating a 15-year-old girl in 1978.

At the first trial, a forestry worker testified to seeing a curly-haired man with a blond girl on a hiking trail the day Robin was abducted, near where the body was later found. Jurors deliberated only a few hours before convicting Alcala on June 20, 1980. He was sentenced to die in the gas chamber.

Alcala won his first new trial in August 1984 after the state Supreme Court said evidence about his other crimes had been improperly allowed.

In the second trial, the forestry worker testified that she had suffered amnesia and no longer remembered the man or the girl. Still, Alcala was again convicted, and sent to San Quentin State Prison to await execution.

But in April 2001, the conviction was again overturned on grounds that Alcala's lawyers should have been allowed to introduce a psychologist's testimony casting doubt on the amnesia claim. Also, Alcala's attorney was faulted for not calling a witness to support his alibi that he was interviewing for a job photographing a disco contest at Knott's Berry Farm when Robin disappeared.

Robin's mother, Marianne Connelly, said during a press conference Monday that she now recognized that if Alcala had been executed soon after his first death sentence, the other victims' families might never have known who killed them.

She said the new charges might allow the families to "get some closure."

"I'm saying that strictly to be noble, I'm sure," she said. "I just wish he was gone."<

Former death-row inmate indicted

Rodney Alcala, facing a possible death penalty for the 1979 slaying of a 12-year-old Huntington Beach girl, has been indicted for killing four women in Los Angeles County more than a quarter century ago.

By Larry Welborn - The Orange County Register

Monday, September 19, 2005

SANTA ANA – Rodney James Alcala, a former death row inmate who was twice convicted of killing a 12-year-old Huntington Beach girl in 1979, has been indicted by the Orange County Grand Jury for the sex-slayings of four Los Angeles County women more than a quarter of a century ago.

Alcala, who is being held without bail, was indicted in Orange County Superior Court today. He is due back in court Oct. 6 to enter a plea.

He is also being investigated for some unsolved murders of women in New York in 1977.

Alcala, 62, has been in custody since July 1979 when he was arrested for the abduction and murder of Robin Samsoe, a Huntington Beach ballet student, who disappeared from her neighborhood on June 20, 1979.

Her decomposing remains were discovered 12 days later in the San Gabriel Mountains.

Twice, Alcala was tried and convicted of the first-degree murder of Samsoe. Twice, he was sentenced death. And twice his convictions were reversed on appeal.

He is back in Orange County Jail now helping his court-appointed attorney George Peters prepare for a third trial in the Samsoe case.

But this time, he could be tried on five murder charges instead of one, if an Orange County Superior Court judge merges the grand jury indictment case with the Samsoe case.

Orange County District Attorney Tony Rackauckas said the four Los Angeles cases are connected to Alcala through DNA testing.

"That's what these cases are about," Rackauckas said. "I think that the ability of law enforcement to analyze DNA is the greatest break through in law enforcement since the two-way radio.

"We knew Alcala was a vicious, merciless killer," Rackauckas added, "But we didn't realize that he was a serial killer to this extent."

The grand jury returned the four-count indictment on Sept. 9, charging Alcala with the strangulation or beating deaths of four women between Nov. 10, 1977 and June 14, 1979.

The indictment, returned after the grand jury heard from 17 witnesses, also alleges that he committed several special circumstances which could lead to a death sentence, including multiple murder, murder by torture, murder during a robbery, and murder during a rape.

The four Los Angeles County slayings are:

-- Nov. 10, 1977: Jill Barcomb, 18, of Oneida, NY, had been in Southern California for about three weeks when her body was found on a dirt path on Mulholland Drive in Los Angeles. She was in a knee-to-chest position and naked from the waist down. She had been strangled with a pair of blue slacks and beaten. There were signs of sexual assault. She also had three bite marks on her right breast, according to the Los Angeles County Coroner's Office.

-- Dec. 16, 1977: Georgia Wixted, 27, was found in her Malibu home, naked, battered and sexually assaulted. A hammer was found next to here body. Wixted was a nurse at Centinela Hospital, was born in New York. Two types of blood were found in her apartment. Alcala was linked to her murder in 2003 when his DNA popped up when authorities tested a sample found at the scene.

-- June 24, 1978: Charlotte Lamb, 32, of Santa Monica, was found naked and dead in the laundry room of a large apartment complex in El Segundo, according to the LA County coroner's office. Lamb, a legal secretary, had been sexually assaulted and strangled with a shoelace. The apartment manager found her body, but residents said they had never seen her before, according to published reports.

-- June 14, 1979: Jill Parenteau, a 21-year-old computer program keypunch operator, was killed after an intruder broke into her Burbank apartment by jimmying window louvers. Her nude body was found on the floor propped up by pillows.

Peters said he has been advised by Orange County prosecutors about the indictment, but he said he has not received any information about the four cases.

"I can't comment until I see what evidence the government has collected," Peters said Thursday. "I can say that Mr. Alcala insists on his innocence in the Robin Samsoe case.

Orange County prosecutors have jurisdiction to prosecute murders that happened elsewhere because state law allows for death penalty cases involving multiple murders to be consolidated in one county, said Los Angeles County Deputy District Attorney Gina T. Satriano, who helped present evidence to the grand jury.

Satriano said Thursday she could not comment on the indictments until today. Orange County Deputy District Attorneys Matt Murphy, the trial prosecutor, and Susan Schroeder, the office's spokesperson, also declined to comment.

Alcala was previously charged with two of the Los Angeles County killings. The other two cases are new.

However, charges against him in Los Angeles County in the Parenteau murder were dismissed in 1981 after an informant's evidence became questionable.

He still faces the murder charge in Los Angeles County in the Wixted case. He was charged with her murder in 2003 after his DNA allegedly matched a sample discovered at the crime scene in Malibu in 1977. DNA testing was not available in the late 1970s.

Former Orange County Deputy District Attorney Richard Farnell, who won a death sentence against Alcala in 1981, said that he attempted to introduce evidence about the 1977 slaying in New York of Ellen Hover, 24, during the death penalty phase of Alcala's case here.

Hover, 24, disappeared from her New York apartment on July 15, 1977, and her body was discovered 11 months later in a shallow grave in a rugged section of the Rockefeller Estate.

Alcala was interviewed about the slaying in 1977 after he moved back to Los Angeles and admitted seeing the woman the day she disappeared, but denied knowing what happened to her. Another woman told authorities that she posed for Alcala's camera on the Rockefeller estate within a 100 feet of where Hover's body was ultimately found.

But the trial judge in Orange County judge disallowed evidence about the Hover killing in the penalty phase of Alcala's trial. He ultimately received the death sentence but it was reversed by an appellate court.

4 deaths added to case against Alcala

Prosecutors pile on charges from L.A. County for retrial of suspect in 1979 kidnap-killing of Huntington child.

By LARRY WELBORN - The Orange County Register

Thursday, September 1, 2005

SANTA ANA – Prosecutors will seek an indictment in Orange County charging Rodney James Alcala with the slayings of four Los Angeles County women more than a quarter of a century ago.

Alcala, who is awaiting a retrial in the 1979 slaying of a Huntington Beach girl, previously was charged with two of the Los Angeles County killings. The charges in one case were dropped in 1981 after an informant's evidence became questionable. Two of the cases are new.

Alcala, 62, has been in custody since July 1979, when he was arrested in the kidnapping of 12-year-old Robin Samsoe, whose skeletal remains were found in the Sierra Madre foothills.

He was twice convicted of the Huntington Beach girl's death, and twice his convictions were reversed on appeal. His third trial is scheduled for next month in Orange County.

An indictment could allow prosecutors to consolidate all five cases and try him in Orange County but would delay the Samsoe retrial.

His attorney, George Peters, said Wednesday that prosecutors sent him a letter stating that they would present evidence to the Orange County grand jury about the slayings of women in Los Angeles County from November 1977 to June 1979.

The letter is on Orange County District Attorney's Office stationery but signed by Gina Satriano, a deputy district attorney in Los Angeles County, Peters said. Satriano and Orange County Deputy District Attorney Matt Murphy, who is prosecuting the Samsoe case, declined to comment.

Peters said he couldn't comment further because he has not been provided with any evidence about the Los Angeles County killings.

"I can say that Mr. Alcala insists on his innocence in the Robin Samsoe case and has said so publicly many times," he said.

The Aug. 24 letter says the four slayings took place Nov. 10, 1977; Dec. 16, 1977; June 24, 1978; and June 14, 1979. The last one was a week before Samsoe disappeared.

In 2003, Los Angeles County prosecutors charged Alcala with the rape and bludgeoning of Georgia Wixted, 28, of Malibu on Dec. 16, 1977, after detectives matched his DNA to samples taken at the crime scene. The charges are pending.

Los Angeles authorities filed and then dropped murder charges against Alcala in the June 1979 slaying of Jill M. Parenteau, 21. Burbank detectives said at the time that Parenteau, a computer programmer, was killed after an intruder broke into her apartment by jimmying window louvers. Blood matching Alcala's type was found at the crime scene, detectives said.

Alcala has never been charged with the killing that took place June 24, 1978.

Los Angeles County coroner's office records show that the nude body of Charlotte Lamb, 32, was found in the laundry room of a large apartment house in El Segundo on that date. She had been strangled.

IN THE COURT OF APPEAL OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA

FOURTH APPELLATE DISTRICT

DIVISION THREE

RODNEY JAMES ALCALA, Petitioner

v.

THE SUPERIOR COURT OF ORANGE COUNTY, Respondent

PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA, Real Party In Interest

G036911

(Super. Ct. No. C42861)

O P I N I O N

Original proceedings; petition for a writ of prohibition/mandate to challenge an order of the Superior Court of Orange County, Briseno, Judge. Petition granted in part and denied in part.

Richard Schwartzberg and George Peters, for Petitioner and Defendant.

No appearance for Respondent.

Tony Rackaukas, Orange County District Attorney, and Brian N. Gurwitz, Deputy District Attorney, for Real Party in Interest.

*****

Rodney James Alcala petitions us for an alternative writ of prohibition or mandate to prevent his single trial on multiple charges of murder which occurred in both Los Angeles County and Orange County. Originally, Alcala faced the single prosecution for the kidnapping and murder of 12-year-old Robin Samsoe that occurred in Orange County in 1979. He was convicted, and the death penalty was imposed. That judgment was reversed in People v. Alcala (1984) 36 Cal.3d 604, 621 (Alcala I), which established a new standard for admitting evidence of other crimes.

Returned to Orange County for retrial, Alcala was again convicted and the death penalty re-imposed, which was affirmed on appeal. (See People v. Alcala (1992) 4 Cal.4th 742, 755 (Alcala II).) This judgment was reversed by an order of a federal district court, which reversal was upheld by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in Alcala v. Woodford (9th Cir. 2003) 334 F.3d 862 (Alcala III) due to ineffective assistance of counsel. (Id. at pp. 865-866.) Again, Alcala returned to Orange County for retrial on the charges of kidnapping and murdering Robin Samsoe in 1979.

In the interim, the California Legislature passed Penal Code section 790, subdivision (b) (790(b)),[1] which provides that if “a defendant is charged with a special circumstance [murder charge], the jurisdiction for any charged murder, and for any crimes properly joinable with that murder, shall be in any county that has jurisdiction . . . for one or more of the murders charged in a single complaint or indictment as long as the charged murders are ‘connected together in their commission,’ as that phrase is used in Section 954, and subject to a hearing in the jurisdiction where the prosecution is attempting to consolidate the charged murders. . . .”

With this statute in mind, the prosecution presented evidence to a grand jury which indicted Alcala for the separate murders of four young women in Los Angeles County in 1977, 1978, and 1979. The prosecution then brought the motion to consolidate the indictment with the case charging Alcala with the kidnapping and murder of Robin under the authority of 790(b).

In addition to the legislative creation of 790(b), the 20-year period between the crimes and the latest trial also saw the passage of Proposition 115. That initiative included a provision, now found in section 954.1 (954.1), that “cases in which two or more different offenses of the same class of crimes . . . have been charged together in the same accusatory pleading, or where two or more accusatory pleadings charging offenses of the same class of crimes . . . have been consolidated, evidence concerning one offense or offenses need not be admissible as to the other offense or offenses before the jointly charged offenses may be tried together . . . .”

After briefing and argument from both parties, the court granted the motion to consolidate and refused any severance. Alcala petitions us to bar the lower court from proceeding on the consolidated case and to sever the Los Angeles murder counts from the Robin Samsoe charges. We grant his petition in part and deny it in part.

FACTS

Robin Samsoe Case

The facts proving the Robin Samsoe case are taken from those laid out in Alcala II. On June 20, 1979, 12-year-old Robin Samsoe spent the afternoon with her girlfriend, Bridget Wilvert, along the cliffs overlooking the beach in Huntington Beach. A man approached them asking to take their pictures for what he represented to be a school contest. The girls posed for him until Jackelyn Young, Wilvert’s neighbor, noticed the man’s suspicious attention on the young girls and interrupted them. The man hurriedly picked up his equipment and left. The man was identified as Alcala.[2] (Alcala II, supra, 4 Cal.4th at pp. 755-757.)

A few minutes later, Samsoe and Wilvert returned to Wilvert’s home where Samsoe borrowed Wilvert’s bike to ride to her beloved ballet class. She was never seen again. (Alcala II, supra, 4 Cal.4th at 755-756.)

Dana Crappa was a seasonal worker for the United States Forestry Service stationed at Chantry Flats, an area near Sierra Madre. Later on the same day Samsoe disappeared, Crappa was driving in the remote region of those hills and came across a Datsun F10 parked on a turnout. There was a dark-haired man pushing or “forcefully steering” (Alcala II, supra, 4 Cal.4th at p. 758) a blond-haired young lady towards a dry stream bed. Crappa did nothing about the sighting even though she thought it strange. The next day, she was again returning to her barracks and had the occasion to pass the same area. The same car was parked nearby the original site, and this time the man was leaning against a nearby rock. He appeared to have dirt or stains all down the front of him. She felt there was something wrong with this scenario, but again told no one and did nothing about it. (Id. at pp. 758-759.) Crappa tentatively identified Alcala as the man she saw.

Five days after the original sighting, Crappa again returned to the site, this time to satisfy her curiosity about the scene. She discovered a mutilated body of a young girl whose head had been partially severed from the body and whose hands and feet had been severed. Surprisingly, she did not report this finding nor did she reveal it to anyone, feeling guilt over not having reported what she had seen five days earlier. It wasn’t until July 2, 1979, that a colleague of Crappa’s discovered some bones in the area and reported it to the authorities. By this time, however, wild animals had so disrupted the decomposed remains that it could not be determined what had caused the death or whether the person had been sexually assaulted. At this time, the skull was completely separated from the spine, and the front teeth were smashed in. A “Kane Kut” kitchen knife was found near the main portion of the remains; and less than a mile away, Samsoe’s beach towel was discovered with blood on it of a type consistent with that drawn from the bone marrow of the remains. Her personalized tennis shoe was found, too, but that was the sole piece of clothing retrieved. (Alcala II, supra, 4 Cal.4th at pp. 758-760.)

In the interim, Wilvert assisted a police composite artist in drawing up a sketch of the man who took the girls’ pictures. That composite sketch was distributed by the media on or about June 22. Alcala’s parole officer saw the sketch and felt it was a match to Alcala, particularly in light of Alcala’s aberrant sexual interest in young girls and his familiarity with the area in which the remains were found, which were matters known to the parole officer. (Alcala II, supra, 4 Cal.4th at p. 756.)

A search warrant was served on the home Alcala shared with his mother in Monterey Park. The police impounded a Datsun F10 parked at the home which was registered to Alcala, inside of which the officers found camera equipment and a briefcase containing a set of keys. Inside the home, they seized sets of Kane Kut kitchen knives and noticed—but failed to seize[3]—a receipt for a storage locker in Seattle, Washington. (Alcala II, supra, 4 Cal.4th at pp. 756-761.)

The storage locker was then searched pursuant to a warrant and the authorities made several interesting discoveries: (1) The keys from Alcala’s briefcase opened both of the two locks put on the locker; (2) in one of the boxes of photographs inside the locker, they found slides taken of Lorraine Werts at the beach on the same day Robin had disappeared; (3) several items of jewelry were found, including a pair of gold ball earrings often worn by Samsoe and which Samsoe’s mother identified as her own, based on a modification she had made by using her nail clippers to alter the surface; and (4) the striations found on those earrings were consistent with marks made by those nail clippers in a test. (Alcala II, supra, 4 Cal.4th at p. 761.)

Alcala’s girlfriend, Elizabeth Kelleher, testified that she saw Alcala on June 22, at which time he was sporting his usual long, curly hair. The next day, however, the composite sketch was exhibited throughout the area. On June 23, Alcala “straightened” his hair using a chemical solution and then cut his hair short on June 26. On July 8, he informed Kelleher that he was going to move from southern California to Texas to start a photography business. However, he actually went to Seattle—not Texas—on July 11. It was at this time he obtained the storage locker. He returned to Monterey Park, informing Kelleher that he planned to leave for Texas permanently on July 24. On the other hand, he told another friend, Leslie Schneider, that he was leaving for Chicago. (Alcala II, supra, 4 Cal.4th at 760.)