Catherine Wilson

Catherine Wilson (1822 - 20 October 1862) was a British woman who was hanged for one murder, but was generally thought at the time to have committed six others.[1] She worked as a nurse and poisoned her victims after encouraging them to leave her money in their wills. She was described privately by the sentencing judge as "the greatest criminal that ever lived.

Crimes

Wilson worked as a nurse first in Spalding, Lincolnshire, and then moving to Kirkby, Cumbria. She married a man called Dixon but her husband soon died, probably poisoned with colchicum, a bottle of which was found in his room. The doctor recommended an autopsy but Wilson begged him not to perform it, and he backed down.

In 1862 Wilson worked as a live-in nurse, nursing a Mrs Sarah Carnell, who rewrote her will in favour of Wilson; soon afterwards, Wilson brought her a "soothing draught", saying "Drink it down, love, it will warm you. Carnell took a mouthful and spat it out, complaining that it had burned her mouth. Later it was noticed that a hole had been burned in the bed clothes by the liquid. Wilson then fled to London, but was arrested a couple of days later.

First trial

The drink she had given to Carnell turned out to contain sulphuric acid - enough to kill 50 people. Wilson claimed that the acid had been mistakenly given to her by the pharmacist who prepared the medicine. She was tried for attempted murder but acquitted. The judge, Mr Baron Bramwell, in the words of Wilson's lawyer Montagu Williams, Q.C., "pointed out that the theory of the defence was an untenable one, as, had the bottle contained the poison when the prisoner received it, it would have become red-hot or would have burst, before she arrived at the invalid's bedside. However, there is no accounting for juries and, at the end of the Judge's summing-up, to the astonishment probably of almost everybody in Court" she was found not guilty.

When Wilson left the dock, she was immediately rearrested, as the police had continued their investigations into Wilson and had exhumed the bodies of some former patients. She was charged with the murder of seven former patients, but tried on just one, Mrs. Maria Soames, who died in 1856. Wilson denied all the charges.

Second trial

Wilson was tried on 25 September 1862 before Mr Justice Byles, again defended by Montague Williams. During the trial it was alleged that seven people whom Wilson had lived with as nurse had died after rewriting their wills to leave her some money, but this evidence was not admitted. Almost all though had suffered from gout. Evidence of colchicine poisoning was given by toxicologist Alfred Swaine Taylor, the defence being that the poison could not be reliably detected after so long. In summing up the judge said to the jury: "Gentlemen, if such a state of things as this were allowed to exist no living person could sit down to a meal in safety". Wilson was found guilty and sentenced to hang. A crowd of 20,000 turned out to see her execution at Newgate Gaol on 20 October 1862. She was the last woman to be publicly hanged in London.4

After the trial, Byles asked Williams to come to his chambers, where he told him: "I sent for you to tell you that you did that case remarkably well. But it was no good; the facts were too strong. I prosecuted Rush for the murder of Mr Jermy, I defended Daniel Good, and I defended several other notable criminals when I was on the Norfolk Circuit; but, if it will be of any satisfaction to you, I may tell you that in my opinion you have to-day defended the greatest criminal that ever lived.

Public reaction to crimes

Wilson's punishment, the first death sentence handed down to a woman by the Central Criminal Court in 14 years, drew little condemnation. In the view of Harper's Weekly, "From the age of fourteen to that of forty-three her career was one of undeviating yet complex vice [...] She was as foul in life as bloody in hand, and she seems not to have spared the poison draught even to the partners of her adultery and sensuality. Hers was an undeviating career of the foulest personal vices and the most cold-blooded and systematic murders, as well as deliberate and treacherous robberies. It was generally thought that Wilson was guilty of more crimes than the one she was convicted of. Harper's went on:

We speak without hesitation of her crimes as plural, because, adopting the language of Mr. Justice Byles with reference to the death of Mrs Soames, we not only 'never heard of a case in which it was more clearly proved that murder had been committed, and where the excruciating pain and agony of the victim were watched with so much deliberation by the murderer,' but also because the same high judicial authority, having access to the depositions in another case, pronounced, in words of unexampled gravity and significance, 'that he had no more doubt but that Mrs Atkinson was also murdered by Catherine Wilson than if he had seen the crime committed with his own eyes.' Nor did these two murders comprise the catalogue of her crimes. That she, who poisoned her paramour Mawer, again poisoned a second lover, one Dixon, robbed and poisoned Mrs Jackson, attempted the life of a third paramour named Taylor, and administered sulphuric acid to a woman in whose house she was a lodger, only in the present year — of all this there seems to be no reasonable doubt, though these several cases have received no regular criminal inquiry. Seven murders known, if not judicially proved, do not after all, perhaps, complete Catherine Wilson's evil career. And if any thing were wanted to add to the magnitude of these crimes it would be found, not only in the artful and devilish facility with which she slid herself into the confidence of the widow and the unprotected — not only in the slow, gradual way in which she first sucked out the substance of her victims before she administered, with fiendish coolness, the successive cups of death under the sacred character of friend and nurse — but in the atrocious malignity by which she sought to destroy the character and reputation of the poor creatures, and to fix the ignominy of suicide on the objects of her own robbery and murder.

The Trial

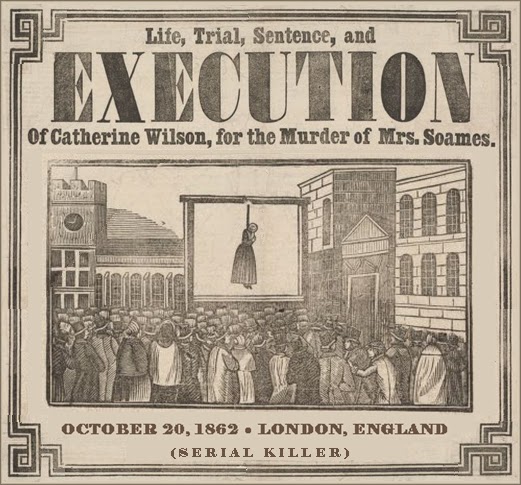

Poster

Several days were occupied at the Central Criminal Court last week in the trial of Catherine Wilson for the murder, by poison, of Mrs. Sonnies six years ago. She was found guilty, and sentenced to death. Her case is interesting as exhibiting the depth of wickedness, of cunning, and of criminal audacity to which woman’s nature may sink. Eight years ago Catherine Wilson was living as housekeeper or servant with a gentleman who made his will in her favour, and very shortly afterwards died. Whether he died by fair means, or whether his death was accelerated by the object of his bounty, will never be known.

There appears no positive evidence of his having died of poison, and charity – if charity is worth bestowing upon such an object – would willingly acquit her of such a crime. The gentleman was accustomed to take doses of colohioum, so that his housekeeper knew perfectly well the mode of its operation – and the seems to have been no idle or thoughtless pupil. Left in moderately comfortable circumstances by the will in her favour, she seems to have devoted her life since that period to improving the fortune and practising the lessons she had obtained from her deceased benefactor by a system of he most wholesale poisoning. Mrs. Soames, the woman of whose murder this female Palmer has just been convicted, kept a lodging-house n London. To this home Mrs. Wilson came as lodger, together with a young man of the name of Dixon. They had not been there long before Dixon was taken seriously and suddenly ill. All the symptoms were those of poisoning by colohioum, and in a short time he died. His mistreat represented that he had died of consumption, but his lungs were found perfectly healthy. A abort time afterwards Mrs. Soames herself came home one evening with a loan of £9 in her pocket. It was dangerous to carry money in one’s pocket when in company with Catherine Wilson. The landlady was well and in good spirits in the evening. Catherine Wilson wanted to see her in her room. She went there, and stayed some time. Next morning she was violently ill — again with the symptoms that would have resulted from the use of colohioum.

Medical assistance was called in; Catherine Wilson was indefatigable in her attentions. She gave her medicine, she gave her food; but the most soothing medicines and the most suitable food only seemed to aggravate the symptoms, and Mrs. Soames died. The £9 she had borrowed was not to be found, while an I O U showed that she was indebted £10 to Catherine Wilson. That she should have borrowed £10 of Catherine Wilson, or that Catherine Wilson should have had £10 to lend her, were equally remarkable. But this was found. The affectionate friend hinted that Mrs. Soames had taken poison – indeed her head seemed to be very full of poison. The doctor suspected poison too, but had not skill enough to prove it. Catherine Wilson, however, knew a cause why she should have taken poison. There was a man who wanted to marry her and had jilted her. Nobody else knew the man, and he has never been produced. There was, however, a letter from him dated just before Mrs. Soames’s death. That letter was proved to be in the handwriting of Catherine Wilson. Such facts as these, with other circumstances ably summed up by the Judge, left not a shadow of doubt that Catherine Wilson had both committed the murder, stolen the money, forged the I O U for money lent, and fabricated the evidence by which she hoped to remove the guilt from her own shoulders.

Three years later, in 1859, we find this interesting creature with a Mrs. Jackson, at Boston. Mrs. Jackson had drawn £120. out of the bank, and Catherine Wilson knew that she had drawn it. Mrs. Jackson was taken ill, with the same symptoms as her former victims, and died. The £120 could not be discovered, and a promissory note which was found for the same, signed by two pretended borrowers, was proved to be a forgery. This sum seems to have set her up, for next year we find her receiving lodgers, and one of these lodgers was a Mrs. Atkinson, of Kirby Lonsdale, who in a short time exhibited the same symptoms as Mrs. Soames and the rest, and in a few days died. The evidence of murder in this case appears to have been very strong, for the prisoner was indicted upon it, and had she been acquitted of the murder of Mrs. Soames would have been tried upon this charge. The Judge, in passing sentence, expressed his firm assurance of her guilt.

An attempt at murder was the only exploit of the next year; and an attempt at murder during the early part of this year, for which she was tried and acquitted, is her only known subsequent achievement.

Catherine Wilson (1822 - 20 October 1862) was a British woman who was hanged for one murder, but was generally thought at the time to have committed six others.[1] She worked as a nurse and poisoned her victims after encouraging them to leave her money in their wills. She was described privately by the sentencing judge as "the greatest criminal that ever lived.

Crimes

Wilson worked as a nurse first in Spalding, Lincolnshire, and then moving to Kirkby, Cumbria. She married a man called Dixon but her husband soon died, probably poisoned with colchicum, a bottle of which was found in his room. The doctor recommended an autopsy but Wilson begged him not to perform it, and he backed down.

In 1862 Wilson worked as a live-in nurse, nursing a Mrs Sarah Carnell, who rewrote her will in favour of Wilson; soon afterwards, Wilson brought her a "soothing draught", saying "Drink it down, love, it will warm you. Carnell took a mouthful and spat it out, complaining that it had burned her mouth. Later it was noticed that a hole had been burned in the bed clothes by the liquid. Wilson then fled to London, but was arrested a couple of days later.

First trial

The drink she had given to Carnell turned out to contain sulphuric acid - enough to kill 50 people. Wilson claimed that the acid had been mistakenly given to her by the pharmacist who prepared the medicine. She was tried for attempted murder but acquitted. The judge, Mr Baron Bramwell, in the words of Wilson's lawyer Montagu Williams, Q.C., "pointed out that the theory of the defence was an untenable one, as, had the bottle contained the poison when the prisoner received it, it would have become red-hot or would have burst, before she arrived at the invalid's bedside. However, there is no accounting for juries and, at the end of the Judge's summing-up, to the astonishment probably of almost everybody in Court" she was found not guilty.

When Wilson left the dock, she was immediately rearrested, as the police had continued their investigations into Wilson and had exhumed the bodies of some former patients. She was charged with the murder of seven former patients, but tried on just one, Mrs. Maria Soames, who died in 1856. Wilson denied all the charges.

Second trial

Wilson was tried on 25 September 1862 before Mr Justice Byles, again defended by Montague Williams. During the trial it was alleged that seven people whom Wilson had lived with as nurse had died after rewriting their wills to leave her some money, but this evidence was not admitted. Almost all though had suffered from gout. Evidence of colchicine poisoning was given by toxicologist Alfred Swaine Taylor, the defence being that the poison could not be reliably detected after so long. In summing up the judge said to the jury: "Gentlemen, if such a state of things as this were allowed to exist no living person could sit down to a meal in safety". Wilson was found guilty and sentenced to hang. A crowd of 20,000 turned out to see her execution at Newgate Gaol on 20 October 1862. She was the last woman to be publicly hanged in London.4

After the trial, Byles asked Williams to come to his chambers, where he told him: "I sent for you to tell you that you did that case remarkably well. But it was no good; the facts were too strong. I prosecuted Rush for the murder of Mr Jermy, I defended Daniel Good, and I defended several other notable criminals when I was on the Norfolk Circuit; but, if it will be of any satisfaction to you, I may tell you that in my opinion you have to-day defended the greatest criminal that ever lived.

Public reaction to crimes

Wilson's punishment, the first death sentence handed down to a woman by the Central Criminal Court in 14 years, drew little condemnation. In the view of Harper's Weekly, "From the age of fourteen to that of forty-three her career was one of undeviating yet complex vice [...] She was as foul in life as bloody in hand, and she seems not to have spared the poison draught even to the partners of her adultery and sensuality. Hers was an undeviating career of the foulest personal vices and the most cold-blooded and systematic murders, as well as deliberate and treacherous robberies. It was generally thought that Wilson was guilty of more crimes than the one she was convicted of. Harper's went on:

We speak without hesitation of her crimes as plural, because, adopting the language of Mr. Justice Byles with reference to the death of Mrs Soames, we not only 'never heard of a case in which it was more clearly proved that murder had been committed, and where the excruciating pain and agony of the victim were watched with so much deliberation by the murderer,' but also because the same high judicial authority, having access to the depositions in another case, pronounced, in words of unexampled gravity and significance, 'that he had no more doubt but that Mrs Atkinson was also murdered by Catherine Wilson than if he had seen the crime committed with his own eyes.' Nor did these two murders comprise the catalogue of her crimes. That she, who poisoned her paramour Mawer, again poisoned a second lover, one Dixon, robbed and poisoned Mrs Jackson, attempted the life of a third paramour named Taylor, and administered sulphuric acid to a woman in whose house she was a lodger, only in the present year — of all this there seems to be no reasonable doubt, though these several cases have received no regular criminal inquiry. Seven murders known, if not judicially proved, do not after all, perhaps, complete Catherine Wilson's evil career. And if any thing were wanted to add to the magnitude of these crimes it would be found, not only in the artful and devilish facility with which she slid herself into the confidence of the widow and the unprotected — not only in the slow, gradual way in which she first sucked out the substance of her victims before she administered, with fiendish coolness, the successive cups of death under the sacred character of friend and nurse — but in the atrocious malignity by which she sought to destroy the character and reputation of the poor creatures, and to fix the ignominy of suicide on the objects of her own robbery and murder.

The Trial

Poster

Several days were occupied at the Central Criminal Court last week in the trial of Catherine Wilson for the murder, by poison, of Mrs. Sonnies six years ago. She was found guilty, and sentenced to death. Her case is interesting as exhibiting the depth of wickedness, of cunning, and of criminal audacity to which woman’s nature may sink. Eight years ago Catherine Wilson was living as housekeeper or servant with a gentleman who made his will in her favour, and very shortly afterwards died. Whether he died by fair means, or whether his death was accelerated by the object of his bounty, will never be known.

There appears no positive evidence of his having died of poison, and charity – if charity is worth bestowing upon such an object – would willingly acquit her of such a crime. The gentleman was accustomed to take doses of colohioum, so that his housekeeper knew perfectly well the mode of its operation – and the seems to have been no idle or thoughtless pupil. Left in moderately comfortable circumstances by the will in her favour, she seems to have devoted her life since that period to improving the fortune and practising the lessons she had obtained from her deceased benefactor by a system of he most wholesale poisoning. Mrs. Soames, the woman of whose murder this female Palmer has just been convicted, kept a lodging-house n London. To this home Mrs. Wilson came as lodger, together with a young man of the name of Dixon. They had not been there long before Dixon was taken seriously and suddenly ill. All the symptoms were those of poisoning by colohioum, and in a short time he died. His mistreat represented that he had died of consumption, but his lungs were found perfectly healthy. A abort time afterwards Mrs. Soames herself came home one evening with a loan of £9 in her pocket. It was dangerous to carry money in one’s pocket when in company with Catherine Wilson. The landlady was well and in good spirits in the evening. Catherine Wilson wanted to see her in her room. She went there, and stayed some time. Next morning she was violently ill — again with the symptoms that would have resulted from the use of colohioum.

Medical assistance was called in; Catherine Wilson was indefatigable in her attentions. She gave her medicine, she gave her food; but the most soothing medicines and the most suitable food only seemed to aggravate the symptoms, and Mrs. Soames died. The £9 she had borrowed was not to be found, while an I O U showed that she was indebted £10 to Catherine Wilson. That she should have borrowed £10 of Catherine Wilson, or that Catherine Wilson should have had £10 to lend her, were equally remarkable. But this was found. The affectionate friend hinted that Mrs. Soames had taken poison – indeed her head seemed to be very full of poison. The doctor suspected poison too, but had not skill enough to prove it. Catherine Wilson, however, knew a cause why she should have taken poison. There was a man who wanted to marry her and had jilted her. Nobody else knew the man, and he has never been produced. There was, however, a letter from him dated just before Mrs. Soames’s death. That letter was proved to be in the handwriting of Catherine Wilson. Such facts as these, with other circumstances ably summed up by the Judge, left not a shadow of doubt that Catherine Wilson had both committed the murder, stolen the money, forged the I O U for money lent, and fabricated the evidence by which she hoped to remove the guilt from her own shoulders.

Three years later, in 1859, we find this interesting creature with a Mrs. Jackson, at Boston. Mrs. Jackson had drawn £120. out of the bank, and Catherine Wilson knew that she had drawn it. Mrs. Jackson was taken ill, with the same symptoms as her former victims, and died. The £120 could not be discovered, and a promissory note which was found for the same, signed by two pretended borrowers, was proved to be a forgery. This sum seems to have set her up, for next year we find her receiving lodgers, and one of these lodgers was a Mrs. Atkinson, of Kirby Lonsdale, who in a short time exhibited the same symptoms as Mrs. Soames and the rest, and in a few days died. The evidence of murder in this case appears to have been very strong, for the prisoner was indicted upon it, and had she been acquitted of the murder of Mrs. Soames would have been tried upon this charge. The Judge, in passing sentence, expressed his firm assurance of her guilt.

An attempt at murder was the only exploit of the next year; and an attempt at murder during the early part of this year, for which she was tried and acquitted, is her only known subsequent achievement.