Genene Anne Jones

Classification: Serial killer

Characteristics: Nurse - Jones seemed to thrill in putting the small children in mortal peril and thrusting herself into the role of hero when the children pulled through

Number of victims: 11 +

Date of murder: 1977 - 1982

Date of arrest: November 21, 1982

Date of birth: July 13, 1950

Victim profile: Infants and children

Method of murder: Poisoning (digoxin, heparin and succinylcholine)

Location: San Antonio, Texas, USA

Status: Sentenced to 99 years in prison on February 15, 1984. Sentenced to a concurrent term of 60 years in prison on October 24, 1984

Working at several medical clinics in and around San Antonio, Texas, nurse Genene Jones practiced possibly the most heinous life-and-death games in American history, injecting innumerable babies with life-threatening drugs. Jones seemed to thrill in putting the small children in mortal peril and thrusting herself into the role of hero when the children pulled through. Unfortunately, many did not.

Though periodically investigated and even being dismissed from two seperate medical facilities when suspicions about infant deaths centered on her, Jones continued to inject babies with chemicals that caused cardiac arrest and hemorraging. She was even directly accused by a fellow nurse before her dismissal from the Bexar County Medical Center, which conducted three seperate investigations into the string of deaths but could never implicate Jones directly.

Jones was finally indicted on charges of poisoning a four-week-old child in January 1982 and she went on trial in January 1984 on the charge of murder. She was sentenced to 99 years in prison and earned another 60 years in a following trial. Her total kills will never be known for sure, but it has been speculated that Jones may have murdered almost 50 helpless infants dating back to the beginning of her nursing career in 1977.

Genene Anne Jones (born July 13, 1950) is a former pediatric nurse who killed somewhere between 11 and 46 infants and children in her care. She used injections of digoxin, heparin and later succinylcholine to induce medical crises in her patients, with the intention of reviving them afterward in order to receive praise and attention.

These medications are known to cause heart paralysis and other complications when given as an overdose. Many children however, did not survive the initial attack and could not be revived. The exact number of murders remain unknown, as hospital officials allegedly first misplaced then destroyed records of her activities to prevent further litigation after Jones' first conviction.

While working at the Bexar County Hospital (now The University Hospital of San Antonio) in the Pediatric Intensive care unit, it was determined that a statistically inordinate number of children Jones worked with were dying. Rather than pursue further investigation the hospital simply asked Jones to resign, which she did.

She then took a position at a pediatric physician's clinic in Kerrville, Texas, near San Antonio. It was here that she was charged with poisoning six children. The doctor in the office discovered puncture marks in a bottle of succinylcholine in the drug storage, where only she and Jones had access. Contents of the apparently full bottle were later found to be diluted. Jones claimed to have been acting in the best interests of her patients, as she was trying to justify the need for a pediatric intensive-care unit in Kerrville. This act was not a successful means of achieving her goal.

In 1985, Jones was sentenced to 99 years in prison for killing 15 month-old Chelsea McClellan with succinylcholine. Later that year, she was sentenced to a concurrent term of 60 years in prison for nearly killing Rolando Jones with heparin. However, she will serve only one-third of her sentence because of a law in place at the time to deal with prison overcrowding. Jones will receive automatic parole in 2017. She is currently eligible for early parole every two to three years, but has been denied six times so far.

She was portrayed by Susan Ruttan in the television movie Deadly Medicine (1991) and by Alicia Bartya in the straight-to-video movie Mass Murder (film) (2002). She was also featured in a Discovery Channel documentary, Lethal Injection, and was said to have inspired Annie Wilkes from Stephen King's Misery.

Genene Jones

VICTIMS : Who can ever tell with this sort of serial killer. I'm assuming 20+

Babies admitted to the intensive care unit had begun dying at an alarming rate; between May and December 1981, the paediatric department of the Bexar County Hospital in San Antonio, Texas, had witnessed the loss of as many as twenty infants through cardiac arrest or runaway bleeding. In the majority of cases death had occurred while the babies were in the care of a licensed vocational nurse named Genene Jones; Miss Jones, though, was widely regarded as a paragon of her profession, and totally dedicated to the care of her small charges.

A series of internal inquiries were held without any positive recommendation, and eventually a panel comprising experts from hospitals in the USA and Canada was appointed to look into the deaths. The panel routinely interviewed members of the Bexar's staff and were surprised when one of her own colleagues bluntly accused Genene Jones of the infants' murder. The panel, as is so often the case, failed to reach any firm conclusion beyond the suggestion that the hospital dispense with the services of both Jones and the nurse who had accused her of killing babies. As a result, there was some acrimony during which Genene Jones resigned from the hospital.

Jones obtained her next appointment at the Kerrville Hospital, where within months of her starting work a number of children began experiencing breathing problems. As they all recovered, no special significance was attached to the incident and no suspicion was directed at Genene Jones. However, when fourteen-month-old Chelsea McClellan was brought to the hospital for regular imminisation against mumps and measles, it was Jones who gave the child her first injection which resulted in an immediate seizure.

On her way to San Antonio for emergency treatment, the McClellan baby went into cardiac arrest and died. Other children receiving their treatment from Genene Jones while she was at Kerrville had attacks of various kinds though no more were fatal. But by now the health authorities had become troubled by the deaths at both hospitals and Jones was dismissed pending a grand jury investigation. News reports had begun to talk of as many as forty-two baby deaths under investigation. The grand jury finally returned indictments against Jones and she was charged with murder following the discovery of succinylchohne, a derivative of the drug curate, in Chelsea McClellan's body.

At her trial during January and February 1984, on a charge of murdering Chelsea McClellan, Genene Jones was found guilty and sentenced to ninety-nine years. She was subsequently put on trial for a second time charged with administering an overdose of the bloodthinning drug heparin to another child; this time she was handed down a concurrent term of sixty years. Although we are unlikely ever to really know what motivated Genene Jones to kill the babies entrusted to her care, there is general agreement that she took pleasure in creating life and death dramas in which she could play an influential role, so indicating a power motive.

This bio was taken from "The Encyclopedia of Serial Killers," by Brian Lane and Wilfred Gregg.

The Wacky World of Murder

Genene Jones (1978-1982) a 27-year old vocational nurse who loved to work with terminally ill children, was convicted to life imprisonment in San Antonio, Texas for 11 murders in 1984.

Because she was mobile, moving around Texas to work in different clinics, authorities expect she may be responsible for as many as 46 deaths.

Her pattern involved injecting heart medication (digoxin) into ailing infants in order to gain recognition as a heroine when she was able to miraculously bring them back from the brink of death, or more commonly, appear as a heroine by taking extraordinary measures to resuscitate the doomed infant.

She brazenly continued her pattern even while she was under a CDC investigation, and her medical supervisors defended her. When she lost the 1984 trial, hospital officials throughout Texas shredded records of her employment and activities, preventing further trials and embarrassment.

Jones, Genene

In February 1983, a special grand jury convened in San Antonio, Texas, investigating the "suspicious" deaths of 47 children at Bexar County's Medical Center Hospital over the past four years.

A similar probe in neighboring Kerr County was focused upon the hospitalization of eight infants who developed respiratory problems during treatment at a local clinic.

One of those children had also died, and authorities were concerned over allegations that deaths in both counties were caused by deliberate injections of muscle relaxing drugs.

Genene Jones, a 32-year-old licensed vocational nurse, was one of three former hospital employees subpoenaed by both grand juries. With nurse Deborah Saltenfuss, Jones had resigned from Medical Center Hospital in March 1982, moving on to a job at the Kerr County clinic run by another subpoenaed witness, Dr. Kathleen Holland.

By the time the grand juries convened, Jones and Holland had both been named as defendants in a lawsuit filed by the parents of 15-month-old Chelsea McClellan, lost en route to the hospital after treatment at Holland's clinic, in September 1982.

On May 26, 1983, Jones was indicted on two counts of murder in Kerr County, charged with injecting lethal doses of a muscle-relaxant and another unknown drug to deliberately cause Chelsea McClellan's death. Additional charges of injury were filed in the cases of six other children, reportedly injected with drugs including succinylincholine during their visits to the Holland clinic.

Facing a maximum sentence of 99 years in prison, Jones was held in lieu of $ 225,000 bond.

An ex-beautician, Jones had entered nursing in 1977, working at several hospitals around San Antonio over the next five years. In early 1982, she followed Dr. Holland in the move to private practice, but her performance at the clinic left much to be desired. In August and September 1982, seven children suffered mysterious seizures while visiting Dr. Holland's office, their cases arousing suspicion at Kerr County's Sip Peterson Hospital, where they were transferred for treatment. Jones was fired from her job on September 26, after "finding" a bottle of succinylincholine reported "lost" three weeks earlier, its plastic cap missing, the rubber top pocked with needle marks.

(In retrospect, Dr. Holland's choice of nurses seemed peculiar, at the very least. Her depositions, filed with the authorities, maintain that hospital administrators had "indirectly cautioned" her against hiring Jones, describing Genene as a possible suspect in hospital deaths dating back to October 1981. Three separate investigations were conducted at Bexar County's hospital between November 1981 and February 1983, all without cracking the string of mysterious deaths.)

On November 21, Jones was indicted in San Antonio, on charges of injuring four-week-old Rolando Santos by deliberately injecting him with heparin, an anticoagulant, in January 1982. Santos had been undergoing treatment for pneumonia when he suffered "spontaneous" hemorrhaging, but physicians managed to save his life.

Their probe continuing, authorities branded Jones as a suspect in at least ten infant deaths at Bexar County's pediatric ward. Genene's murder trial opened at Georgetown, Texas, on January 15, 1984, with prosecutors introducing an ego motive. Like New York's Richard Angelo, Jones allegedly sought to become a hero or "miracle worker" by "saving" children in life-and-death situations.

Nurses from Bexar County also recalled Genene's plan to promote a pediatric intensive care unit in San Antonio, ostensibly by raising the number of seriously-ill children. "They're out there," she once told a colleague. "All you have to do is find them."

Jurors deliberated for three hours before convicting Jones of murder on February 15, fixing her penalty at 99 years in prison. Eight months later, on October 24, she was convicted of injuring Rolando Santos in San Antonio, sentenced to a concurrent term of 60 years.

Suspected in at least ten other homicides, Jones was spared further prosecution when Bexar County hospital administrators shredded 9,000 pounds of pharmaceutical records in March 1984, destroying numerous pieces of evidence then under subpoena by the local grand jury.

Michael Newton - An Encyclopedia of Modern Serial Killers - Hunting Humans

Genene Jones (1950 - still living) was a pediatric nurse who worked in several medical clinics around San Antonio, Texas and is thought to have killed somewhere between 11 and 46 infants and children who were in her care.

An accurate number may never be known, in part because after her conviction on one count of murder and one count of attempted murder, hospital officials throughout Texas shredded records of her employment and activities, preventing further trials and embarrassment.

In 1985 Jones was charged with two crimes and sentenced to 99 years in prison. Due to a law that was in place at the time of her conviction to deal with prison over-crowding, Jones will only be forced to serve 1/3 of her sentence. The law stated that for every one year served, three years of time-served credit would be given to the convicted. Jones will receive automatic parole in 2017, much to the protest of the family of Chelsea McClellan, the child Jones was convicted of murdering.

Jones is eligible for parole every two - three years, having been denied six times so far.

Genene Jones

Genene worked as a nurse in the Paediatric department of the Bexar County Hospital in San Antonio, Texas. She was well respected and considered to be totally dedicated to the job of nursing sick babies. Even so in the short period of May to December 1981 20 babies died from either Cardiac Arrest or bleeding.

A number of investigations were conducted to look into the circumstances and to see if any improvements could be made which would reduce the infant mortality rate. To help them with their investigations the members of the investigating team interviewed a number of hospital staff. No real conclusions had been reached when one nurse openly accused a colleague of being responsible for the deaths. As they had no real evidence to back this up it was decided that the easiest way out of this would be to ask the nurse concerned to resign which they did.

The nurse in question was Nurse Genene Jones. Just to tidy up any loose ends they also asked the nurse who had accused her to resign as well.

Nurse Jones soon got herself a job at the Kerriville Hospital. All started well but within a few months there was an increase in young children experiencing breathing difficulties. None were in a serious condition and all recovered and its relevance did not occur to anyone at that time.

Chelsea McClellan who was fourteen months old was brought into hospital for a routine immunisation against Mumps and Measles. Genene Jones was responsible for giving the child the injection and immediately after the child suffered a seizure. The baby was rushed to San Antonio for emergency treatment but on the way suffered a cardiac arrest and died. It seemed that many of the children that were treated by Genene had various attacks and seizures but none were fatal.

Even so the authorities were beginnng to take notice and had looked into Nurse Jones's past and knew about the earlier deaths. Even though they had little evidence they decided to dismiss her pending a grand jury hearing. Further investigation indicated that the number of deaths in question could be as many as forty two. She was finally charged with murder after an autopsy revealed traces of Succinylcholine in the body of Chealsea McClellan. Succinylcholine is a derivative of the drug Curare.

Her trial lasted through January and February of 1984 and she was found guilty and sentenced to ninety nine years for the murder of Chealsea McClellan. She was then charged with a second murder. This time she was accused of giving a child the drug Heparin which has the effect of thinning down the blood and therefore making it difficult for it to clot. Again she was found guilty and sentenced to sixty years to run concurrently.

Although it will never really be known why she murdered these children the belief is that by creating a life and death situation she was putting herself in a position of power.

The Caretaker

In 1982, Dr. Kathleen Holland opened a pediatrics clinic in Kerville, Texas. She hired a licensed vocational nurse named Genene Ann Jones, who had recently resigned from the Bexar County Medical Center Hospital. Then over the next two months, seven children had seizures. The staff at the hospital where she transported them was suspicious. Holland had no idea what to say, and then one of the children died.

However, a bottle of succinylcholine, a powerful muscle relaxant, had turned up missing, and then suddenly Genene Jones located it. Holland dismissed Jones, and was later to learn that the bottle had been filled with saline. In other words, someone had been using this dangerous drug.

It wasn't the first time Jones had been in trouble.

In February 1983, a grand jury was convened to look into 47 suspicious deaths of children at Bexar County Medical Center Hospital that had occurred over a period of four years---the time when she had been a nurse there. A second grand jury organized hearings on the children from Holland's clinic. The body of Chelsea McClellan was exhumed and her tissues tested; her death appeared to have been caused by an injection of the muscle relaxant.

The grand jury indicted Jones on two counts of murder, and several charges of injury to six other children. Anyone who knew Jones was not altogether surprised. She could be inordinately aggressive, had betrayed friends, and often resorted to lies to manipulate others---a classic psychopath. While she'd wanted children all her life, the two she had she'd left in the care of her adoptive mother.

The first child she picked up in her job at Bexar County Medical had a fatal intestinal condition, and when he died shortly thereafter, she went berserk. She brought a stool into the cubicle where the body lay and sat staring at it.

By 1981, Jones demanded to be put in charge of the sickest patients. That placed her close to those that died most often. She loved the excitement of an emergency, and even seemed to enjoy the grief she experienced when a child didn't make it. She always wanted to take the corpse to the morgue.

It became clear to everyone that children were dying in this unit from problems that shouldn't have been fatal. The need for resuscitation suddenly seemed constant---but only when Jones was around. Those in the most critical condition were all under her care. One child had a seizure three days in a row, but only on her shift. "They're going to start thinking I'm the Death Nurse," Jones quipped one day.

Then a baby named Jose Antonio Flores, six months old, went into cardiac arrest while in Jones's care. He was revived, but went into arrest again the next day during her shift and died from bleeding. Tests on the corpse indicated an overdose of a drug called Heparin, an anticoagulant. No one had ordered it.

Then Rolando Santos, being treated for pneumonia, was having seizures, cardiac arrest, and extensive unexplained bleeding. All of his troubles developed or intensified on Jones's shift. Finally one doctor stepped forward and told the hospital staff that she was killing children. They needed an investigation. Yet the nurses protected her. Since the hospital did not want bad publicity, they accepted whatever the head nurse said.

Another child was sent to the pediatrics unit to recover from open-heart surgery. At first, he progressed well, but on Jones's shift, he became lethargic. Then his condition deteriorated and he soon died. Jones grabbed a syringe and squirted fluid over the child in the sign of a cross, then repeated it on herself.

Finally, a committee was formed to look into the problem. They decided to replace the LVNs with RNs on the unit, and Jones promptly resigned. To their mind, that took care of the problem.

All it did was let her know she could get away with medical abuse, and she moved on to the Kerrville clinic. Despite the risk of exposure in such a small place to inject children to the point of seizure, she didn't stop.

Although Dr. Holland was warned in veiled tones not to hire Genene Jones, she viewed Jones as a victim of the male-dominated patriarchy. She had no idea that by teaming up with this woman, she was about to kill her own career, her marriage, and one of her young charges.

At trial, prosecutors presented Jones as having a hero complex: She needed to take the children to the edge of death and then bring them back so that she could be acclaimed their savior. One of her former colleagues reported that she wanted to get more sick children into the intensive care unit. "They're out there," she supposedly said. "All you have to do is find them."

Yet her actions may actually have been inspired by a more mundane motive: She liked the excitement and the attention it brought her. The children couldn't tell on her; they were at her mercy. So she was free to recreate emergencies over and over.

In a statistical report presented at the second trial, an investigator stated that children were 25% more likely to have a cardiac arrest when Jones was in charge, and 10% more likely to die.

On February 15, 1982, Jones was convicted of murder. Later that year, she was found guilty of injuring another child by injection. The two sentences totaled 159 years, but she's eligible for parole after 20.

Clearly, Jones made the deliberate effort to kill, but not all female killers are as aggressive. Yet denial can still play a part in the tragedies they cause, as was the case with the next woman, who became quite famous for her unintentional crimes.

Too Young to Die

Petti McClellan took her blond, blue-eyed baby daughter Chelsea into the new pediatric clinic. It was Friday, September 17, 1982. The clinic had just opened the day before in Kerrville, Texas, not far from the trailer home where she and her husband Reid lived. Chelsea was just 8 months old, but she had a cold, and her mother wanted to be safe. Chelsea had been born premature, with underdeveloped lungs, so she was prone to infection. Early in her life, she had spent time on a hospital respirator. She had also experienced what Petti described as "spells" of losing her breath. Chelsea was the clinic's very first patient.

In Women Who Kill, Carol Anne Davis (who bases much of her account on Deadly Medicine) wrote that pediatric nurse Genene Jones took the child to another area of the clinic to play with a ball while Dr. Kathleen Holland talked with the mother. Soon after, Jones told them that Chelsea had stopped breathing. She placed an oxygen mask over the baby’s face and they rushed her to an emergency room at nearby Sid Peterson Hospital. To everyone's relief, the child recovered. Chelsea's parents were grateful that such a competent nurse was on staff there. They spread the word to other parents.

Nine months later, they brought Chelsea in again. This time the results were drastically different. Peter Elkind, a journalist who briefly met Genene Jones, offers a fuller account in The Death Shift.

“Chelsea was the first appointment of the day, just a routine check-up. Petti McClellan brought her in around midmorning, and Dr. Holland ordered two standard inoculations. Shortly after nurse Genene Jones injected the first needle, Chelsea started having trouble breathing. It appeared that she was having a seizure, so McClellan asked her to stop. Jones ignored her and gave the child a second injection. Then Chelsea stopped breathing altogether. She jerked around as if trying to breathe, and then went limp.”

An ambulance was called and they transported Chelsea to Sid Peterson Hospital, where she arrived in nine minutes with a breathing tube down her throat. Jones carried the child in her arms all the way there. Chelsea tried to remove the tube, so Dr. Holland replaced it with a larger one and then gave her something to make her sleep. Jones allegedly said, "And they said there wouldn't be any excitement when we came to Kerrville." In fact, there was to be plenty of excitement at that clinic—more than most clinics get--and Jones was always at the center.

Holland arranged to transport Chelsea to a hospital where neurological tests could be performed, and while she was in the ambulance, Chelsea stopped breathing again and her heart stopped. Jones gave her several injections while Dr. Holland performed a heart massage, but there was no response. They pulled into a nearby hospital and continued treatment. But after 20 minutes it was clear that they had failed. Chelsea McClellan was dead.

Jones sobbed over the body as she cleaned it up and wrapped it in a blanket for the McClellans. Petti McClellan believed that her daughter was merely asleep. No matter what anyone said to her, she could not come to terms with the fact that Chelsea was dead.

They all returned to Sid Peterson Hospital, and Jones carried the child downstairs to the hospital morgue. Dr. Holland wanted an autopsy. She was not going to just let this go as a cardiac arrest. The whole thing had been too unusual. Chelsea had not even come in with a complaint. She had been there for a routine examination.

The autopsy was performed and Holland waited for the results. In the meantime, the McClellans arranged the funeral. After a few weeks, it was determined that Chelsea had died of SIDS, an often fatal breathing dysfunction in babies. But new tests would later challenge that conclusion.

Petti McClellan was unable to cope, according to Elkind. At the funeral, she screamed and fainted, and her relatives sent her to get psychiatric help. Thanks to that, she had spent a considerable amount of time in a haze, but the sharp grief had not yet dulled.

One day, a week after the funeral, she went to the Garden of Memories Cemetery to lay flowers on her daughter's grave.

As she approached the grave, she saw the nurse from the clinic, Genene Jones. Oddly, she was kneeling at the foot of Chelsea's grave, sobbing and wailing the child's name over and over. She rocked back and forth, apparently in deep anguish, as if Chelsea had been her own daughter.

"What are you doing here?" McClellan asked. Did this nurse feel guilty about her role in Chelsea's death? Perhaps she had neglected to do something that had made the crucial difference?

Confronted, Jones returned a blank stare, as if in a trance, and walked away without a word. When she was gone, McClellan noticed something else. While Jones had left a small token of flowers, she had taken a bow from Chelsea's grave.

Wrong Turns

In The Encyclopedia of Serial Killers, Michael Newton describes Jones’ background. She had been a beautician before going into nursing in 1977 and had worked at several hospitals in the San Antonio area. Peter Elkind says that she had claimed to have grown up feeling unwanted and unloved.

Genene was born on July 13, 1950, and was immediately given up for adoption. Her new parents were Dick and Gladys Jones, who adopted three other children as well—two older and one younger than Genene. They lived in a two-story, four-bedroom mansion just outside San Antonio. Dick was an entrepreneur and professional gambler. He worked in the entertainment business, operating nightclubs. Somewhat larger-than-life, he was free-spending and generous, but his lifestyle eventually took a toll on his family. The nightclub went south and there was less money to spend. Jones tried a restaurant, but that venture failed, too.

When Genene was 10, her father was arrested. It seems that a large safe had turned up missing from a home owned by a man who had been at Jones' club at the time of the burglary. There was $1,500 in cash and some valuable jewelry inside. A priest turned it over to police, protecting the one who had given it to him, but the police went after Dick Jones. He confessed but claimed the episode was a practical joke. The charges were dropped.

Then Jones opened a billboard business. For Genene, according to Carol Anne Davis in Women Who Kill, riding around in the truck with her father while he put up billboards was the happiest time of her life. Other than that, she had a hard time getting attention. She felt left out and unfavored by her parents. She went around calling herself the family's "black sheep."

Sometimes she would pretend to be ill in order to get people to notice, and at school she became bossy. She was short and overweight, which added to her loneliness. There were acquaintances who called her aggressive and friends who said she had betrayed them. She was known for lying and manipulating people.

Genene was close to her younger brother, Travis, who loved to be in their father's shop. When he was 14, he put together a pipe bomb that blew up in his face, killing him. Genene was 16 at the time, and during the funeral, she screamed and fainted. She had lost her closest companion. Some believe this trauma fed her peculiar cruelty. Others said she was just histrionic and grabbed any opportunity for attention.

During her senior year of high school, Genene's father began to get sick. He was diagnosed with terminal cancer, refused treatment and went home to die. He made it through Christmas 1967, but died shortly afterward at the age of 56, just over a year after the death of Travis.

Genene was devastated and, though she hadn’t yet finished high school, believed that the remedy to her pain and loss was to get married right away. She and her mother fought over it and Gladys soon turned to the bottle, getting drunk frequently but refusing to give permission for Genene to marry. It was too soon after the family tragedies.

Finally when Genene graduated, she married a high school dropout, James “Jimmy” Harvey DeLany Jr. (Davis claims that she trapped this man into marrying her by pretending she was pregnant.) He, too, was overweight, and he cared only about hot rods. After seven months of marriage, he enlisted in the navy and Genene, who was reportedly voracious in her desire for sex, was immediately unfaithful. Intense and dramatic, she went after other men as if to fill the void left by her father's untimely death, and she bragged openly about it. She even had affairs with married men and she began to spread rumors that she had been sexually abused as a child.

She depended on her mother for money, so Gladys urged her to think about a career. With no real plans, Genene enrolled in beauty school. Jimmy returned from the navy and they had a child. After four years of marriage, she left her husband while he was recovering in the hospital from a boating accident. Her divorce papers indicated that he had been violent with her. They reconciled and then parted again for good.

Soon after, Genene's older brother died of cancer. It was yet another loss, and her developing fear of cancer from working with hair dyes made a career change necessary. She had worked in a hospital beauty salon, so it wasn't a far stretch to train as a nurse. She was also pregnant, so now she had two children to care for. Although she had wanted children all her life, she ended up leaving them in the care of her adoptive mother.

Genene had reserved her special ardor for doctors, seeing them as mysterious and powerful. She wanted to get near them, so she trained for a year to become a vocational nurse, and LVN or licensed vocational nurse. She was good at it, although she was not altogether happy about being at the bottom of the medical totem pole. Her interest in medicine began to take on mystical dimensions and, as acquaintances put it, she became obsessed with diagnosing people.

After only eight months at her first job at San Antonio's Methodist Hospital, she was fired, in part because she tried to make decisions in areas where she had no authority, and in part because she made rude demands on a patient who subsequently complained. It wasn't difficult for her to find another job, but she didn't last long in that one either. Eventually she was hired in the intensive care section of the pediatric unit of Bexar County Medical Center Hospital. It was here that she would leave her mark—a tragic one.

Her Own Special Shift

The first child she picked up had a fatal intestinal condition, and when he died shortly after surgery, she went berserk. She brought a stool into the cubicle where the body lay and sat staring at it. The other nurses could not understand her behavior. She hadn't even known the child and had barely been around him, so why the excessive grief?

It soon became clear to associates that Genene liked to feel needed, and she would often spend long hours on the ward during her 3-11 p.m. shift, insisting that her attention was important to a certain patient. However, she skipped classes on the proper handling of drugs and in her first year made eight separate nursing errors, including while dispensing medication. She sometimes developed a dependency on sick children, so she would refuse specific orders because she wanted to do what was "best" for the child.

While there were sufficient grounds for dismissal, including coming in one night drunk, the head nurse Pat Belko liked and protected her, which gave Jones a feeling of invincibility. She never liked to admit any mistakes, and now she had someone in power to back her up. She tried to bully new nurses into looking to her for help, and more than one nurse transferred out of the unit to get away from her.

As she took charge, Genene grew more arrogant, aggressive and foul-mouthed. She liked to talk about her sexual conquests, both past and future. Not many people liked her. She would make harrowing predictions about which baby was going to die, which upset the new nurses she was training.

Then a new doctor came to the ward, James Robotham. Hired as the medical director of the pediatric intensive care unit, he took more responsibility for patients than other doctors had, and that meant edging out the nurses. He also made them more accountable, which didn't sit well with them. All except for Genene, who welcomed the opportunity to bring more problems to someone's attention—because that meant attention for her.

Her other means for getting noticed was to go to outpatient clinics for minor physical complaints of her own, which Elkind says she did 30 times in just over two years. Although she was never officially diagnosed, she may have been suffering from a form of Munchausen Syndrome, in which people become "hospital hoboes" to get attention from caring staff that they feel they missed out on as children. Even when Genene wasn't at some county clinic, she was complaining about her health and seeking some leverage with it. One physician said her problems were psychosomatic.

In 1981, Jones demanded to be put in charge of the sickest patients. That placed her close to those who died. She seemed to thrive on the excitement of an emergency and even on grief when a child didn't make it. While she prepared a body, she would sing to it and she always wanted to take the corpse to the morgue. This routine was a regular procession, with a security guard walking ahead of her to close patients' doors. Genene often cried as she performed this task, but then again, it did seem as if she liked to cry.

No one seemed concerned that many medications were freely available on that ward in an unlocked cabinet -- not until later. Nor did they give any thought to the fact that the hospital where Genene had last worked had not given a reason for her dismissal. No one followed up, although Genene was placed in a role of significant responsibility. Her special talent, Elkind points out, was putting intravenous tubes into veins. She requested special seminars handling certain drugs and asked many questions. People were impressed by how much she wanted to learn.

It eventually became clear to everyone that children were dying in this unit from problems that shouldn't have been fatal. Davis claims there was one two-week period where seven children died. The need for resuscitation suddenly seemed constant---but only when Genene was around. Those in the most critical condition were all under her care. There was no denying the excitement that an emergency situation engendered, and Genene even commented on several occasions that it was "an incredible experience." One child had a seizure three days in a row, but only on her shift.

"They're going to start thinking I'm the Death Nurse," Jones quipped one day. In fact, some of the staff called her on-duty hours the Death Shift, based on the many resuscitations that were going on during the hours she was there—and the many deaths.

She even seemed to enjoy calling parents to let them know about their child's death and to commiserate. If a baby's health was bad, she would announce to the other nurses, "Tonight is the night." If a child was near death, she always took a special interest. She clearly wanted to be there when it happened.

While rumors were passed around that Genene was doing something to these children, Pat Belko defended her. It was just gossip from nurses who were jealous of her competence. She refused to listen.

Then a baby named Jose Antonio Flores, six months old, came in with some common childhood symptoms: fever, vomiting and diarrhea. While in Genene's care, he developed unexplained seizures and went into cardiac arrest.

The Death Shift

It took doctors almost an hour to save young Jose, but they did. They noticed he was bleeding badly and they could not determine the cause. They found that his blood was not clotting, but eventually the problem subsided and he seemed okay -- until the following day during the 3-11 shift.

Once again, Jose went into seizures and began to bleed. Early the next morning, his heart stopped beating. Cause of death: unknown.

When a doctor told Jose’s father about losing his son, the man had a heart attack. While helping Mr. Flores to the emergency room, Genene allowed Jose's older brother to carry the baby’s body. Then she grabbed the dead baby and ran down the hospital corridor. Several members of the family ran after her. She lost them and went into the morgue. No one could figure out what her behavior meant, but blood testing on the body indicated an overdose of a drug called heparin, an anticoagulant. No one had ordered it, and her superiors became suspicious.

Then two resident physicians who were treating a 3-month-old boy named Albert Garza found that Genene probably gave him an overdose of heparin. When they confronted her, she got angry and left, but the child recovered. This incident also resulted in tighter control over the staff’s use of heparin, making nurses more accountable and records more precise. Children whose health declined were to be subject to extra lab tests. If someone was doing something to children on this ward, she was going to get caught.

It was at this point that Genene's health seemed to be suffering. She also refused drugs prescribed by doctors to improve her condition. Often when she complained of something, there was no evidence for it. Again, it appeared she was angling for attention. Dr. Robotham, who had once been her ally, began to complain formally about Genene Jones.

In November 1981, the hospital administration, somewhat resistant to an internal investigation of the pediatrics ward, had a meeting. They decided that Dr. Robotham was overreacting. The struggling hospital did not need the possibility that such suspicions would come to the public's attention, so they declined to follow through. Yet that did not end Robotham's efforts to launch a formal investigation. He continued to watch the records of the 3-11 shift.

While heparin use was carefully monitored, another drug suddenly showed up in the death of Joshua Sawyer, age 11 months. He was brought in suffering from the effects of smoke inhalation after a fire at his home. He'd had a cardiac arrest, and doctors ordered Dilantin. He remained in a coma, but doctors expected him to make progress. Genene told his parents that he would be better off if allowed to die, however, since he would surely have serious brain damage. Then quite suddenly, Joshua had two heart attacks and died. His lab tests showed a toxic amount of Dilantin in his blood. Clearly someone's handling at the hospital had killed him, but the test results went unnoticed.

When Genene became aware that those who had always supported her were now suspicious, she turned to blackmail. She said she had records on every child that had died there and she knew which doctor had killed them. Robotham requested that she be fired, but no one listened. They also did not listen to the nurse who kept reporting that supplies were missing.

Then Rolando Santos, a 1-month-old baby being treated for pneumonia, was suddenly having seizures, cardiac arrest, and extensive unexplained bleeding. All of his troubles developed or intensified on Genene's shift. He began to urinate so badly that he suffered extreme dehydration. For the three days Genene had off, the baby improved, but the afternoon she returned, he began to hemorrhage. Then he had a heart attack. Lab tests showed an excessive amount of heparin. Initially, a doctor took over his care, but after Genene got hold of him, he worsened again and went into a coma. Blood came up into his throat and his blood pressure dropped dangerously. A doctor saved him and then ordered him removed from the pediatric ICU and placed under 24-hour surveillance. Only under these conditions did he improve enough to be released to his parents. Rolando survived his encounter with Genene Jones. He was one of the lucky ones.

Finally one more doctor stepped forward to tell the hospital administration that Genene Jones, the afternoon shift nurse, was killing children. He had found a manual in her possessions about how to inject heparin subcutaneously without leaving a mark, and he had evidence of how Rolando Santos had suffered during Genene Jones’ working hours. The hospital resisted, however, not wanting bad press.

Another child was sent to the pediatrics unit to recover from open-heart surgery. At first, he progressed well, but on Genene's shift, he became lethargic. Then his condition deteriorated and he died. The doctors were puzzled and could only attribute his death to some infection. In view of everyone in the room where the child had succumbed, Genene grabbed a syringe and squirted fluid over his forehead in the sign of a cross, then repeated it on herself. She grabbed the dead baby and began to cry.

More doctors complained and finally a committee was formed to look into the problem. Pat Belko and James Robotham were in charge. An outside team of investigators came in and determined that there was clearly a problem, but they declined to pin it on a single nurse. In the end, the committee decided to replace the LVNs on the unit with RNs, which meant that Genene would be transferred away from the babies. She reacted to this change by resigning. The administrators were relieved. In their minds, that took care of the problem.

All it did, however, was transfer the problem. The medical emergencies on the afternoon shift returned to manageable numbers, but they started up elsewhere.

Death Moves On

In 1982, Dr. Kathleen Holland opened a pediatrics clinic in Kerrville, Texas. Needing help, she hired Genene Jones. She had worked at Bexar County Hospital with her and had even testified on her behalf during the investigation. Although Dr. Holland was warned in veiled tones not to hire Genene, she went ahead and did it, viewing Genene as a victim of the male-dominated medical patriarchy. She believed that Genene was a competent nurse who just needed a chance, and she gave her the title pediatric clinician. According to Carol Anne Davis, Holland helped to move Genene to Kerrville and rented rooms to her and her two children.

Just months after Genene left Bexar, someone found a novel with her name in it called The Sisterhood, written by best-selling ER physician Michael Palmer. The plot centered on a group of medical professionals who were pledged to end human suffering by terminating patients who they believed would be better off dead. They had a specific protocol in place to ensure the most careful scrutiny, but as always in fiction, someone took things too far.

In Murder Most Rare, Michael D. Kelleher and C.L. Kelleher reserve a chapter for “lethal caretakers,” medical professionals who kill their patients. This contemporary form of the Angel of Death, they say, "embodies an especially pernicious darkness in our humanity by systematically attacking the weak and defenseless who have been involuntarily placed into her care or must rely on her for comfort and support." These people carry out their crimes within institutions where chemicals and syringes are abundant and where they can hide their behavior for long periods of time. Typically they select patients whose deaths are explainable because they were in some weakened or near-fatal condition already. Easy to kill, easy to cover up.

Yet what motivates these people? "Ego and a compulsion for domination," say the authors. "She is obsessed with the need to control those who are completely dependent on her. Some, like Genene Jones, are also motivated by a need for attention. While they appear to be going about their routines, they are making decisions about who should live and who should die. What happens to the patient does not matter to the caretakers; what matters is what the incident does for them.”

Many parents around Kerrville were happy to have Dr. Holland's clinic available, but during a period of two months that first summer, seven different children succumbed to seizures while in her office. In one case, Genene told a worried mother that the child was just having a tantrum---an understatement that nearly cost the child her life. Holland transferred each of them by ambulance to Kerr County's Sid Peterson Hospital, never thinking the seizures were suspicious. Yet Genene's accounts of these incidents always differed from those of other professionals involved—and one of them had seen her inject something into a child who then had seizures. From the sheer numbers of children afflicted in the same clinic, the hospital staff thought something odd must be going on, especially since the kids always recovered quickly while in the hospital.

Holland assumed the severity of the situation was because she was a specialist, not a generalist, so the worst cases were brought to her. At least they had all recovered.

But then Chelsea McClellan died while en route from the hospital to another facility. Dr. Holland was devastated, as were Chelsea's parents. The child had not even been very ill. The same day, after Genene had returned to the clinic to see another patient, the boy went into seizures and had to be resuscitated. The child stabilized and his parents later commented that Genene had appeared to be quite excited over the incident, even happy. Tests afterward indicated there was no reason for such an unexpected episode.

At about that time, a doctor at Sid Peterson discovered the high number of baby deaths at the hospital where Genene Jones had previously worked. He brought this to the attention of a committee, and they began to realize that she was doing something to these children. They brought in Dr. Holland and asked if she was using succinylcholine, a powerful muscle relaxant. She said she had some in her office but did not use it. Without telling her, someone on the committee notified the Texas Rangers.

Holland told Genene about the meeting, and Genene assured Dr. Holland that she had found the bottle of succinylcholine that was missing. The cap was gone, and Holland began to have suspicions.

On September 27, while Genene was at lunch, Dr. Holland examined the bottles of succinylcholine. They were both nearly full, but one of them had pinprick holes through the rubber stopper. When Genene could not give a credible accounting of it and even suggested they just throw the bottle away to avoid questions, Dr. Holland was alarmed. She later learned that the near-full bottle had been filled with saline. In other words, someone had been using a lot of this dangerous drug, which paralyzed people into a sort of hell on earth: they lay inert but aware and unable to get anyone's attention.

Before she could take any action, Dr. Holland was faced with another crisis: Genene told her that she had taken an overdose of doxepin, a drug to fight anxiety. She had to have her stomach pumped, but it turned out that she had not overdosed at all. She had taken only four of the pills, but she had faked a semi-coma, forcing emergency personnel to treat her.

Then Holland discovered that another bottle of succinylcholine had been ordered but was missing. On September 28, she fired Genene and offered any help she could to the investigation.

Even so, families left her practice and Sid Peterson suspended her privileges. For hiring Genene Jones, Holland was losing everything. Even her husband divorced her. On top of that, she saw evidence that Genene was trying to frame her and she began to fear for her own life.

Justice

On October 12, 1982, a grand jury in Kerr County organized hearings on the eight children from Holland's clinic who had developed emergency respiratory problems and the one who had died—Chelsea McClellan. Her body was exhumed to examine the tissues with an expensive test that had just been developed in Sweden to detect the presence of succinylcholine. The test showed that her death appeared to have been caused by an injection of the muscle relaxant. However, it was exceedingly difficult to get real proof against the nurse. No one had seen her give the actual injection.

In February 1983, another grand jury was convened in San Antonio, to look into a stunning total of 47 suspicious deaths of children at Bexar County Medical Center Hospital. All had occurred over a period of four years and all coincided with Genene Jones's tenure at that facility. There was plenty of testimony from coworkers about Genene's behavior, but again, no real proof.

Three former Bexar employees, including Jones, then 32, were questioned by both grand juries. Dr. Holland was also questioned, and Chelsea's parents named her and Jones in a wrongful death suit. Holland had turned against Genene, offering the district attorney ammunition against her former nurse, specifically in her discovery of the bottles of succinylcholine.

At some point, Genene married a 19-year-old boy, possibly to deflect tabloid rumors that she was a lesbian. She was caught trying to flee with him.

The Kerr County grand jury concluded first and indicted Jones on one count of murder in Kerr County, and several charges of injury to seven other children who had been injected with muscle-relaxing drugs. For these, she faced a possible sentence of 99 years and she was held in the Kerr County jail in lieu of a $225,000 bond.

Then in November, the San Antonio grand jury indicted her for injuring four-week-old boy Rolando Santos with a deliberate injection of heparin almost two years earlier. He had nearly died from it. Jones remained a suspect in 10 other infant deaths at the hospital.

Administrators at the facilities where she had worked were appalled. They were also embarrassed, because it became increasingly clear that they had known something and had not acted.

While awaiting trial Jones supposedly told someone, according to Elkind, "I always cry when babies die. You can almost explain away an adult death. When you look at an adult die, you can say they've had a full life. When a baby dies, they've been cheated."

She claimed she was receiving death threats, although the notes she showed people bore the same handwriting and misspellings as those she herself had sent to a nurse once in San Antonio. When her trial was moved to a new venue in Georgetown, Texas, her attorney asked to be replaced. She gave interviews freely to reporters that undermined his attempts to build a defense and he feared that she would do the same on the witness stand.

There were two separate trials, and the first one began on January 15, 1984, for the murder of Chelsea McClellan and injury to other children.

Prosecutors said Genene Jones had a hero complex: She needed to take the children to the edge of death and then bring them back so that she could be acclaimed their savior. One of her former colleagues reported that she had wanted to get more sick children into the intensive care unit. "They're out there," she supposedly said. "All you have to do is find them." Witnesses testified that she would contradict herself by telling one person she had injected a specific type of substance, and another person that it was something else. All in all, her pattern of behavior was clearly suspicious, including the fact that she had asked for an educational seminar specifically on the use of succinylcholine.

Yet her actions may actually have been inspired by a more mundane motive: She liked the excitement and the attention it brought her. There was no doubt that her behavior had escalated and that she had taken more risks. The children couldn't tell on her; they were at her mercy. She was free to create emergencies over and over. It was Munchausen syndrome by proxy: getting attention from doctors by making someone else sick.

No one raised the possibility that Genene had acted out something that had been done to her as a child. While she had hinted at abuse to friends, there was no one to confirm that.

Much of this was replayed at the second trial, but specifically in regard to her behavior at Bexar. In a statistical report presented at that trial, an investigator stated that children were 25% more likely to have a cardiac arrest when Jones was in charge and 10% more likely to die. A psychiatric exam failed to provide her with the testimony she would need for an insanity defense. Instead, her lawyer brought in witnesses to testify that Genene was devoted, competent and responsible.

The first jury deliberated for only three hours. On February 15, 1984, Jones was convicted of murder and she was given the maximum sentence of 99 years. Later that year, in October, she was found guilty of the charge of injuring Rolando Santos by injection. The two sentences totaled 159 years, but with the possibility of parole.

Although she was suspected in the deaths of other children, the staff at the Bexar County Medical Center Hospital shredded 9,000 pounds of pharmaceutical records, thus destroying potential evidence that was under the grand jury's subpoena.

Most of those at Bexar who had protected her ended up resigning, and the clinic settled the legal suit brought by the McClellans.

Jones came up for parole after 10 years, but relatives of Chelsea McClellan successfully fought to keep her behind bars, where she will remain until at least 2009, when she is again eligible for parole.

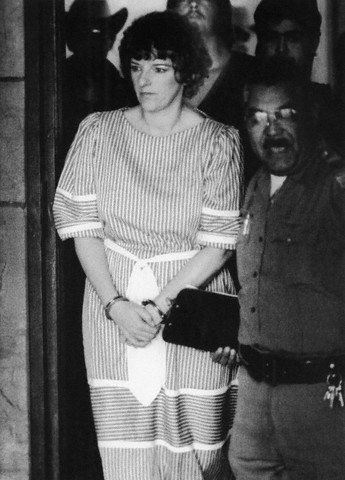

Convicted baby killer Genene Jones, shown here after a pre-trial hearing on October 1, 1984.

Jones is thought to have murdered between 11 and 46 infants in her care, between 1980 and

1982. She was convicted of killing one infant, Chelsea McClellan, and nearly killing another,

Rolando Jones, earning her a 159 years total in prison.

only victim avail since almost all were children

In 1985, Jones was sentenced to 99 years in prison for killing 15 month-old

Chelsea McClellan with succinylcholine.

Classification: Serial killer

Characteristics: Nurse - Jones seemed to thrill in putting the small children in mortal peril and thrusting herself into the role of hero when the children pulled through

Number of victims: 11 +

Date of murder: 1977 - 1982

Date of arrest: November 21, 1982

Date of birth: July 13, 1950

Victim profile: Infants and children

Method of murder: Poisoning (digoxin, heparin and succinylcholine)

Location: San Antonio, Texas, USA

Status: Sentenced to 99 years in prison on February 15, 1984. Sentenced to a concurrent term of 60 years in prison on October 24, 1984

Working at several medical clinics in and around San Antonio, Texas, nurse Genene Jones practiced possibly the most heinous life-and-death games in American history, injecting innumerable babies with life-threatening drugs. Jones seemed to thrill in putting the small children in mortal peril and thrusting herself into the role of hero when the children pulled through. Unfortunately, many did not.

Though periodically investigated and even being dismissed from two seperate medical facilities when suspicions about infant deaths centered on her, Jones continued to inject babies with chemicals that caused cardiac arrest and hemorraging. She was even directly accused by a fellow nurse before her dismissal from the Bexar County Medical Center, which conducted three seperate investigations into the string of deaths but could never implicate Jones directly.

Jones was finally indicted on charges of poisoning a four-week-old child in January 1982 and she went on trial in January 1984 on the charge of murder. She was sentenced to 99 years in prison and earned another 60 years in a following trial. Her total kills will never be known for sure, but it has been speculated that Jones may have murdered almost 50 helpless infants dating back to the beginning of her nursing career in 1977.

Genene Anne Jones (born July 13, 1950) is a former pediatric nurse who killed somewhere between 11 and 46 infants and children in her care. She used injections of digoxin, heparin and later succinylcholine to induce medical crises in her patients, with the intention of reviving them afterward in order to receive praise and attention.

These medications are known to cause heart paralysis and other complications when given as an overdose. Many children however, did not survive the initial attack and could not be revived. The exact number of murders remain unknown, as hospital officials allegedly first misplaced then destroyed records of her activities to prevent further litigation after Jones' first conviction.

While working at the Bexar County Hospital (now The University Hospital of San Antonio) in the Pediatric Intensive care unit, it was determined that a statistically inordinate number of children Jones worked with were dying. Rather than pursue further investigation the hospital simply asked Jones to resign, which she did.

She then took a position at a pediatric physician's clinic in Kerrville, Texas, near San Antonio. It was here that she was charged with poisoning six children. The doctor in the office discovered puncture marks in a bottle of succinylcholine in the drug storage, where only she and Jones had access. Contents of the apparently full bottle were later found to be diluted. Jones claimed to have been acting in the best interests of her patients, as she was trying to justify the need for a pediatric intensive-care unit in Kerrville. This act was not a successful means of achieving her goal.

In 1985, Jones was sentenced to 99 years in prison for killing 15 month-old Chelsea McClellan with succinylcholine. Later that year, she was sentenced to a concurrent term of 60 years in prison for nearly killing Rolando Jones with heparin. However, she will serve only one-third of her sentence because of a law in place at the time to deal with prison overcrowding. Jones will receive automatic parole in 2017. She is currently eligible for early parole every two to three years, but has been denied six times so far.

She was portrayed by Susan Ruttan in the television movie Deadly Medicine (1991) and by Alicia Bartya in the straight-to-video movie Mass Murder (film) (2002). She was also featured in a Discovery Channel documentary, Lethal Injection, and was said to have inspired Annie Wilkes from Stephen King's Misery.

Genene Jones

VICTIMS : Who can ever tell with this sort of serial killer. I'm assuming 20+

Babies admitted to the intensive care unit had begun dying at an alarming rate; between May and December 1981, the paediatric department of the Bexar County Hospital in San Antonio, Texas, had witnessed the loss of as many as twenty infants through cardiac arrest or runaway bleeding. In the majority of cases death had occurred while the babies were in the care of a licensed vocational nurse named Genene Jones; Miss Jones, though, was widely regarded as a paragon of her profession, and totally dedicated to the care of her small charges.

A series of internal inquiries were held without any positive recommendation, and eventually a panel comprising experts from hospitals in the USA and Canada was appointed to look into the deaths. The panel routinely interviewed members of the Bexar's staff and were surprised when one of her own colleagues bluntly accused Genene Jones of the infants' murder. The panel, as is so often the case, failed to reach any firm conclusion beyond the suggestion that the hospital dispense with the services of both Jones and the nurse who had accused her of killing babies. As a result, there was some acrimony during which Genene Jones resigned from the hospital.

Jones obtained her next appointment at the Kerrville Hospital, where within months of her starting work a number of children began experiencing breathing problems. As they all recovered, no special significance was attached to the incident and no suspicion was directed at Genene Jones. However, when fourteen-month-old Chelsea McClellan was brought to the hospital for regular imminisation against mumps and measles, it was Jones who gave the child her first injection which resulted in an immediate seizure.

On her way to San Antonio for emergency treatment, the McClellan baby went into cardiac arrest and died. Other children receiving their treatment from Genene Jones while she was at Kerrville had attacks of various kinds though no more were fatal. But by now the health authorities had become troubled by the deaths at both hospitals and Jones was dismissed pending a grand jury investigation. News reports had begun to talk of as many as forty-two baby deaths under investigation. The grand jury finally returned indictments against Jones and she was charged with murder following the discovery of succinylchohne, a derivative of the drug curate, in Chelsea McClellan's body.

At her trial during January and February 1984, on a charge of murdering Chelsea McClellan, Genene Jones was found guilty and sentenced to ninety-nine years. She was subsequently put on trial for a second time charged with administering an overdose of the bloodthinning drug heparin to another child; this time she was handed down a concurrent term of sixty years. Although we are unlikely ever to really know what motivated Genene Jones to kill the babies entrusted to her care, there is general agreement that she took pleasure in creating life and death dramas in which she could play an influential role, so indicating a power motive.

This bio was taken from "The Encyclopedia of Serial Killers," by Brian Lane and Wilfred Gregg.

The Wacky World of Murder

Genene Jones (1978-1982) a 27-year old vocational nurse who loved to work with terminally ill children, was convicted to life imprisonment in San Antonio, Texas for 11 murders in 1984.

Because she was mobile, moving around Texas to work in different clinics, authorities expect she may be responsible for as many as 46 deaths.

Her pattern involved injecting heart medication (digoxin) into ailing infants in order to gain recognition as a heroine when she was able to miraculously bring them back from the brink of death, or more commonly, appear as a heroine by taking extraordinary measures to resuscitate the doomed infant.

She brazenly continued her pattern even while she was under a CDC investigation, and her medical supervisors defended her. When she lost the 1984 trial, hospital officials throughout Texas shredded records of her employment and activities, preventing further trials and embarrassment.

Jones, Genene

In February 1983, a special grand jury convened in San Antonio, Texas, investigating the "suspicious" deaths of 47 children at Bexar County's Medical Center Hospital over the past four years.

A similar probe in neighboring Kerr County was focused upon the hospitalization of eight infants who developed respiratory problems during treatment at a local clinic.

One of those children had also died, and authorities were concerned over allegations that deaths in both counties were caused by deliberate injections of muscle relaxing drugs.

Genene Jones, a 32-year-old licensed vocational nurse, was one of three former hospital employees subpoenaed by both grand juries. With nurse Deborah Saltenfuss, Jones had resigned from Medical Center Hospital in March 1982, moving on to a job at the Kerr County clinic run by another subpoenaed witness, Dr. Kathleen Holland.

By the time the grand juries convened, Jones and Holland had both been named as defendants in a lawsuit filed by the parents of 15-month-old Chelsea McClellan, lost en route to the hospital after treatment at Holland's clinic, in September 1982.

On May 26, 1983, Jones was indicted on two counts of murder in Kerr County, charged with injecting lethal doses of a muscle-relaxant and another unknown drug to deliberately cause Chelsea McClellan's death. Additional charges of injury were filed in the cases of six other children, reportedly injected with drugs including succinylincholine during their visits to the Holland clinic.

Facing a maximum sentence of 99 years in prison, Jones was held in lieu of $ 225,000 bond.

An ex-beautician, Jones had entered nursing in 1977, working at several hospitals around San Antonio over the next five years. In early 1982, she followed Dr. Holland in the move to private practice, but her performance at the clinic left much to be desired. In August and September 1982, seven children suffered mysterious seizures while visiting Dr. Holland's office, their cases arousing suspicion at Kerr County's Sip Peterson Hospital, where they were transferred for treatment. Jones was fired from her job on September 26, after "finding" a bottle of succinylincholine reported "lost" three weeks earlier, its plastic cap missing, the rubber top pocked with needle marks.

(In retrospect, Dr. Holland's choice of nurses seemed peculiar, at the very least. Her depositions, filed with the authorities, maintain that hospital administrators had "indirectly cautioned" her against hiring Jones, describing Genene as a possible suspect in hospital deaths dating back to October 1981. Three separate investigations were conducted at Bexar County's hospital between November 1981 and February 1983, all without cracking the string of mysterious deaths.)

On November 21, Jones was indicted in San Antonio, on charges of injuring four-week-old Rolando Santos by deliberately injecting him with heparin, an anticoagulant, in January 1982. Santos had been undergoing treatment for pneumonia when he suffered "spontaneous" hemorrhaging, but physicians managed to save his life.

Their probe continuing, authorities branded Jones as a suspect in at least ten infant deaths at Bexar County's pediatric ward. Genene's murder trial opened at Georgetown, Texas, on January 15, 1984, with prosecutors introducing an ego motive. Like New York's Richard Angelo, Jones allegedly sought to become a hero or "miracle worker" by "saving" children in life-and-death situations.

Nurses from Bexar County also recalled Genene's plan to promote a pediatric intensive care unit in San Antonio, ostensibly by raising the number of seriously-ill children. "They're out there," she once told a colleague. "All you have to do is find them."

Jurors deliberated for three hours before convicting Jones of murder on February 15, fixing her penalty at 99 years in prison. Eight months later, on October 24, she was convicted of injuring Rolando Santos in San Antonio, sentenced to a concurrent term of 60 years.

Suspected in at least ten other homicides, Jones was spared further prosecution when Bexar County hospital administrators shredded 9,000 pounds of pharmaceutical records in March 1984, destroying numerous pieces of evidence then under subpoena by the local grand jury.

Michael Newton - An Encyclopedia of Modern Serial Killers - Hunting Humans

Genene Jones (1950 - still living) was a pediatric nurse who worked in several medical clinics around San Antonio, Texas and is thought to have killed somewhere between 11 and 46 infants and children who were in her care.

An accurate number may never be known, in part because after her conviction on one count of murder and one count of attempted murder, hospital officials throughout Texas shredded records of her employment and activities, preventing further trials and embarrassment.

In 1985 Jones was charged with two crimes and sentenced to 99 years in prison. Due to a law that was in place at the time of her conviction to deal with prison over-crowding, Jones will only be forced to serve 1/3 of her sentence. The law stated that for every one year served, three years of time-served credit would be given to the convicted. Jones will receive automatic parole in 2017, much to the protest of the family of Chelsea McClellan, the child Jones was convicted of murdering.

Jones is eligible for parole every two - three years, having been denied six times so far.

Genene Jones

Genene worked as a nurse in the Paediatric department of the Bexar County Hospital in San Antonio, Texas. She was well respected and considered to be totally dedicated to the job of nursing sick babies. Even so in the short period of May to December 1981 20 babies died from either Cardiac Arrest or bleeding.

A number of investigations were conducted to look into the circumstances and to see if any improvements could be made which would reduce the infant mortality rate. To help them with their investigations the members of the investigating team interviewed a number of hospital staff. No real conclusions had been reached when one nurse openly accused a colleague of being responsible for the deaths. As they had no real evidence to back this up it was decided that the easiest way out of this would be to ask the nurse concerned to resign which they did.

The nurse in question was Nurse Genene Jones. Just to tidy up any loose ends they also asked the nurse who had accused her to resign as well.

Nurse Jones soon got herself a job at the Kerriville Hospital. All started well but within a few months there was an increase in young children experiencing breathing difficulties. None were in a serious condition and all recovered and its relevance did not occur to anyone at that time.

Chelsea McClellan who was fourteen months old was brought into hospital for a routine immunisation against Mumps and Measles. Genene Jones was responsible for giving the child the injection and immediately after the child suffered a seizure. The baby was rushed to San Antonio for emergency treatment but on the way suffered a cardiac arrest and died. It seemed that many of the children that were treated by Genene had various attacks and seizures but none were fatal.

Even so the authorities were beginnng to take notice and had looked into Nurse Jones's past and knew about the earlier deaths. Even though they had little evidence they decided to dismiss her pending a grand jury hearing. Further investigation indicated that the number of deaths in question could be as many as forty two. She was finally charged with murder after an autopsy revealed traces of Succinylcholine in the body of Chealsea McClellan. Succinylcholine is a derivative of the drug Curare.

Her trial lasted through January and February of 1984 and she was found guilty and sentenced to ninety nine years for the murder of Chealsea McClellan. She was then charged with a second murder. This time she was accused of giving a child the drug Heparin which has the effect of thinning down the blood and therefore making it difficult for it to clot. Again she was found guilty and sentenced to sixty years to run concurrently.

Although it will never really be known why she murdered these children the belief is that by creating a life and death situation she was putting herself in a position of power.

The Caretaker

In 1982, Dr. Kathleen Holland opened a pediatrics clinic in Kerville, Texas. She hired a licensed vocational nurse named Genene Ann Jones, who had recently resigned from the Bexar County Medical Center Hospital. Then over the next two months, seven children had seizures. The staff at the hospital where she transported them was suspicious. Holland had no idea what to say, and then one of the children died.

However, a bottle of succinylcholine, a powerful muscle relaxant, had turned up missing, and then suddenly Genene Jones located it. Holland dismissed Jones, and was later to learn that the bottle had been filled with saline. In other words, someone had been using this dangerous drug.

It wasn't the first time Jones had been in trouble.

In February 1983, a grand jury was convened to look into 47 suspicious deaths of children at Bexar County Medical Center Hospital that had occurred over a period of four years---the time when she had been a nurse there. A second grand jury organized hearings on the children from Holland's clinic. The body of Chelsea McClellan was exhumed and her tissues tested; her death appeared to have been caused by an injection of the muscle relaxant.

The grand jury indicted Jones on two counts of murder, and several charges of injury to six other children. Anyone who knew Jones was not altogether surprised. She could be inordinately aggressive, had betrayed friends, and often resorted to lies to manipulate others---a classic psychopath. While she'd wanted children all her life, the two she had she'd left in the care of her adoptive mother.

The first child she picked up in her job at Bexar County Medical had a fatal intestinal condition, and when he died shortly thereafter, she went berserk. She brought a stool into the cubicle where the body lay and sat staring at it.

By 1981, Jones demanded to be put in charge of the sickest patients. That placed her close to those that died most often. She loved the excitement of an emergency, and even seemed to enjoy the grief she experienced when a child didn't make it. She always wanted to take the corpse to the morgue.

It became clear to everyone that children were dying in this unit from problems that shouldn't have been fatal. The need for resuscitation suddenly seemed constant---but only when Jones was around. Those in the most critical condition were all under her care. One child had a seizure three days in a row, but only on her shift. "They're going to start thinking I'm the Death Nurse," Jones quipped one day.

Then a baby named Jose Antonio Flores, six months old, went into cardiac arrest while in Jones's care. He was revived, but went into arrest again the next day during her shift and died from bleeding. Tests on the corpse indicated an overdose of a drug called Heparin, an anticoagulant. No one had ordered it.

Then Rolando Santos, being treated for pneumonia, was having seizures, cardiac arrest, and extensive unexplained bleeding. All of his troubles developed or intensified on Jones's shift. Finally one doctor stepped forward and told the hospital staff that she was killing children. They needed an investigation. Yet the nurses protected her. Since the hospital did not want bad publicity, they accepted whatever the head nurse said.

Another child was sent to the pediatrics unit to recover from open-heart surgery. At first, he progressed well, but on Jones's shift, he became lethargic. Then his condition deteriorated and he soon died. Jones grabbed a syringe and squirted fluid over the child in the sign of a cross, then repeated it on herself.

Finally, a committee was formed to look into the problem. They decided to replace the LVNs with RNs on the unit, and Jones promptly resigned. To their mind, that took care of the problem.

All it did was let her know she could get away with medical abuse, and she moved on to the Kerrville clinic. Despite the risk of exposure in such a small place to inject children to the point of seizure, she didn't stop.

Although Dr. Holland was warned in veiled tones not to hire Genene Jones, she viewed Jones as a victim of the male-dominated patriarchy. She had no idea that by teaming up with this woman, she was about to kill her own career, her marriage, and one of her young charges.

At trial, prosecutors presented Jones as having a hero complex: She needed to take the children to the edge of death and then bring them back so that she could be acclaimed their savior. One of her former colleagues reported that she wanted to get more sick children into the intensive care unit. "They're out there," she supposedly said. "All you have to do is find them."

Yet her actions may actually have been inspired by a more mundane motive: She liked the excitement and the attention it brought her. The children couldn't tell on her; they were at her mercy. So she was free to recreate emergencies over and over.

In a statistical report presented at the second trial, an investigator stated that children were 25% more likely to have a cardiac arrest when Jones was in charge, and 10% more likely to die.

On February 15, 1982, Jones was convicted of murder. Later that year, she was found guilty of injuring another child by injection. The two sentences totaled 159 years, but she's eligible for parole after 20.

Clearly, Jones made the deliberate effort to kill, but not all female killers are as aggressive. Yet denial can still play a part in the tragedies they cause, as was the case with the next woman, who became quite famous for her unintentional crimes.

Too Young to Die