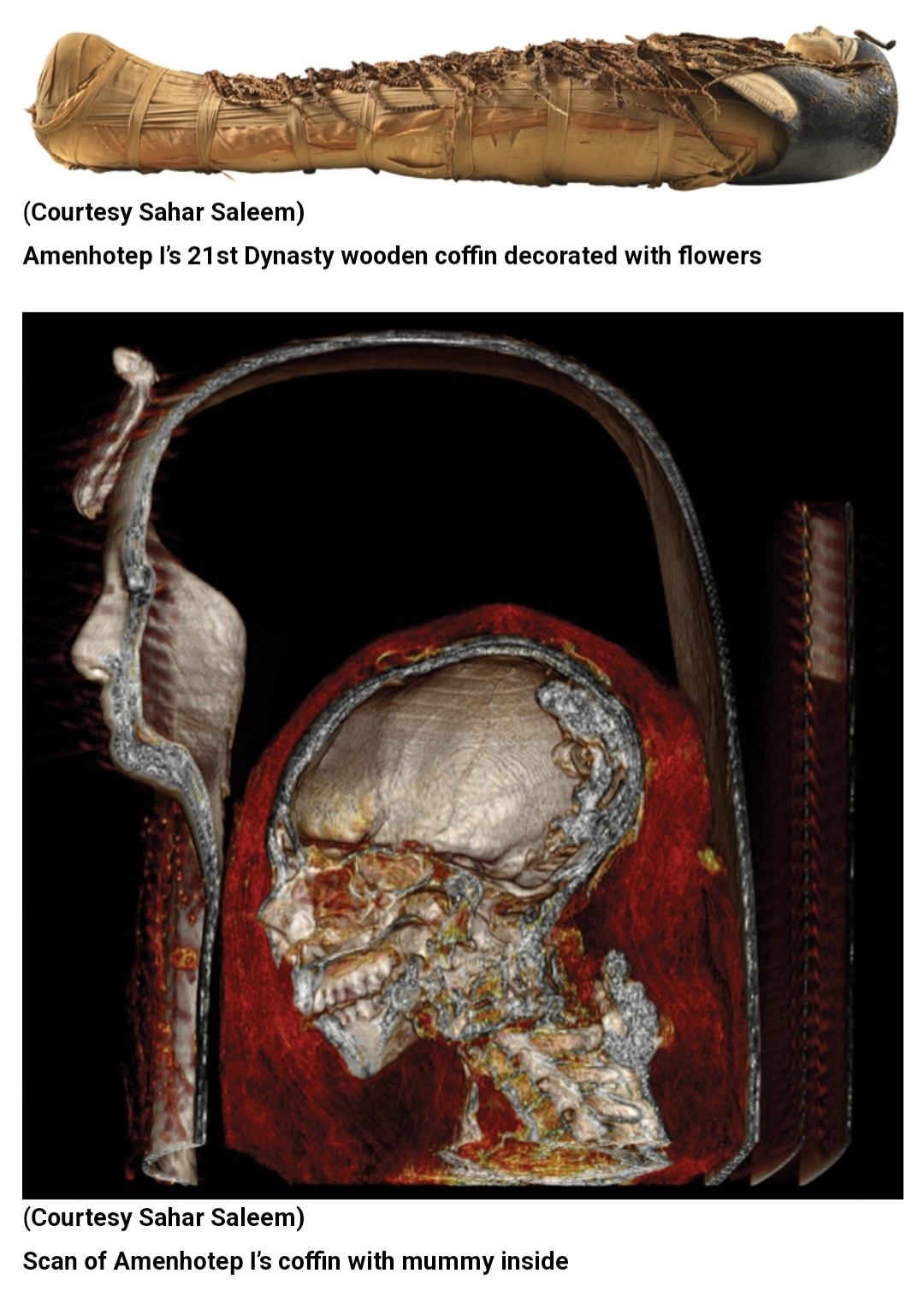

It’s not every day that scientists have the opportunity to look inside the coffin of a member of ancient Egyptian royalty—and to do so without opening it might seem impossible. But the sarcophagus containing the pharaoh Amenhotep I (reigned ca. 1525–1504 B.C.) has now been virtually opened and the mummy inside virtually unwrapped, revealing a wealth of new information about one of Egypt’s great rulers. Amenhotep I’s mummy, which was found in 1881, is one of very few known royal mummies that have not been unwrapped in modern times. During the Victorian era, wealthy patrons threw many exclusive mummy unwrapping parties. “The mummy was never unwrapped because scholars at the time thought it was too beautiful to destroy,” says radiologist Sahar Saleem of Cairo University, who led the project. Using noninvasive CT scanning, Saleem has generated 3-D images of the pharaoh’s mask, bandages, body, and face. “To see the pharaoh’s face after 3,000 years and how much he resembled his father, Ahmose, was very moving,” she says.

Amenhotep I’s mummy was not found in its original burial location but in the ancient town of Deir el-Bahari, where it was part of a cache of mummies, many of them royal as well. These mummies had been collected during the 21st Dynasty (ca. 1070–945 B.C.) by priests who rewrapped and reinterred them in new coffins. Many of the cache’s mummies had been badly damaged by tomb robbers before being collected. Saleem’s scans show that the priests who rewrapped and reinterred Amenhotep I’s mummy carefully reattached his head with a resin-treated linen band. His neck had been broken, likely when looters tore off a necklace. They also rearranged his broken left arm, covered a hole in his stomach, and placed gold amulets inside. “The study provides evidence for the great care taken by the priests of the 21st Dynasty in reburying the mummy of Amenhotep I, preserving the golden ornaments, and placing many amulets inside,” Saleem says. “This restores confidence in the goodwill of the priests to rebury the royal mummies to preserve them, contrary to modern allegations that the goal was to steal the ornaments.” She was also able to see that the pharaoh’s right arm had been folded over his chest in its original mummification position. “Folding the arms on the chest became characteristic of royal mummies to make them resemble Osiris, god of the afterlife,” Saleem says. “Amenhotep I’s mummy is the first example of this style of mummification, which later became standard for all ancient Egyptian mummies.”

Amenhotep I’s mummy was not found in its original burial location but in the ancient town of Deir el-Bahari, where it was part of a cache of mummies, many of them royal as well. These mummies had been collected during the 21st Dynasty (ca. 1070–945 B.C.) by priests who rewrapped and reinterred them in new coffins. Many of the cache’s mummies had been badly damaged by tomb robbers before being collected. Saleem’s scans show that the priests who rewrapped and reinterred Amenhotep I’s mummy carefully reattached his head with a resin-treated linen band. His neck had been broken, likely when looters tore off a necklace. They also rearranged his broken left arm, covered a hole in his stomach, and placed gold amulets inside. “The study provides evidence for the great care taken by the priests of the 21st Dynasty in reburying the mummy of Amenhotep I, preserving the golden ornaments, and placing many amulets inside,” Saleem says. “This restores confidence in the goodwill of the priests to rebury the royal mummies to preserve them, contrary to modern allegations that the goal was to steal the ornaments.” She was also able to see that the pharaoh’s right arm had been folded over his chest in its original mummification position. “Folding the arms on the chest became characteristic of royal mummies to make them resemble Osiris, god of the afterlife,” Saleem says. “Amenhotep I’s mummy is the first example of this style of mummification, which later became standard for all ancient Egyptian mummies.”