they should have sterilised her or at least made it a condition of her release that she did not get anywhere close to children. She was complicit in the killing of her own sister! Imagine having that perverted raping killing pig for a teacher!Karla Holmoka now goes by the name Emily Bordelais and is married and had her 3rd child in 2011! She lives in the Carribean, and believe it or not is A School Teacher!! What A world we live in!!!

Navigation

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature currently requires accessing the site using the built-in Safari browser.

More options

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Female Serial Killer Thread (1 Viewer)

- Thread starter p4irs

- Start date

Users who are viewing this thread

Total: 2 (members: 0, guests: 2)

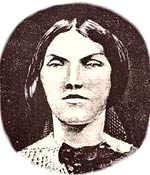

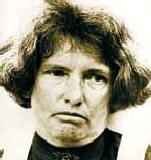

Aileen Wuornos

Aileen Carol Wuornos (February 29, 1956 – October 9, 2002) was an American serial killer who killed seven men in Florida between 1989 and 1990, claiming they raped or attempted to rape her while she was working as a prostitute. She was convicted and sentenced to death for six of the murders, and executed via lethal injection on October 9, 2002.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aileen_Wuornos

check out her interview, look at her eyes, and she did pass the insanity test LOL

[/quote]

Kinda thinking the women have the men beat when it comes to wiping you off this green earth! lol,. Aileen Wuornos wasn't a stupid woman though. A few things she said were a little out there, but most of her words were the truth. There is such things as sonic frequencies, they use them in the movies to this very day. The frequencies adjust your moods throughout the whole movie! Music industry uses it as well. I know a bunch of cops, and even a female detective. They definitely know who the prostitutes are in town. And many of them can easily take advantage of the situation. I don't know .. I kinda have mixed reviews about her sentencing..

Aileen Carol Wuornos (February 29, 1956 – October 9, 2002) was an American serial killer who killed seven men in Florida between 1989 and 1990, claiming they raped or attempted to rape her while she was working as a prostitute. She was convicted and sentenced to death for six of the murders, and executed via lethal injection on October 9, 2002.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aileen_Wuornos

check out her interview, look at her eyes, and she did pass the insanity test LOL

[/quote]

Kinda thinking the women have the men beat when it comes to wiping you off this green earth! lol,. Aileen Wuornos wasn't a stupid woman though. A few things she said were a little out there, but most of her words were the truth. There is such things as sonic frequencies, they use them in the movies to this very day. The frequencies adjust your moods throughout the whole movie! Music industry uses it as well. I know a bunch of cops, and even a female detective. They definitely know who the prostitutes are in town. And many of them can easily take advantage of the situation. I don't know .. I kinda have mixed reviews about her sentencing..

A serial killer kills 3 or more victims, with a cooling off period of at least 24 hours between. A mass murderer kills a shitload of people at the same location in 1 continuous period. A spree killer kills 2 or more victims in more than 1 location, again, with no cooling off period.What exactly makes someone a serial killer rather than a mass murderer or spree killer?

Is there a certain time frame or body count?

smutpeddler

NewbieX

I love all this shit, but when it comes to infants.. I can't stand that. Especially pictures of them. Just pisses me off.

limitfluid

NewbieX

i love Aileen man its cause of her circumstance in life that most serial kilers become serial killers RIP cant wait to meet You on the other side

limitfluid

NewbieX

i love Aileen man its cause of her circumstance in life that most serial kilers become serial killers RIP cant wait to meet You on the other side

Electricaliens

Lurker

i actually sympathize for her i wish they hadnt put her to death. One day she will rise up out of the ashes and get her revenge Har Har Har

Aileen Wuornos

Aileen Carol Wuornos (February 29, 1956 – October 9, 2002) was an American serial killer who killed seven men in Florida between 1989 and 1990, claiming they raped or attempted to rape her while she was working as a prostitute. She was convicted and sentenced to death for six of the murders, and executed via lethal injection on October 9, 2002.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aileen_Wuornos

check out her interview, look at her eyes, and she did pass the insanity test LOL

Kinda thinking the women have the men beat when it comes to wiping you off this green earth! lol,. Aileen Wuornos wasn't a stupid woman though. A few things she said were a little out there, but most of her words were the truth. There is such things as sonic frequencies, they use them in the movies to this very day. The frequencies adjust your moods throughout the whole movie! Music industry uses it as well. I know a bunch of cops, and even a female detective. They definitely know who the prostitutes are in town. And many of them can easily take advantage of the situation. I don't know .. I kinda have mixed reviews about her sentencing..[/quote]

bet ya didnt know she was a lez and totally hated men if i remember right her g/friend was involved with a couple of the killings....

Aileen Wuornos

Aileen Carol Wuornos (February 29, 1956 – October 9, 2002) was an American serial killer who killed seven men in Florida between 1989 and 1990, claiming they raped or attempted to rape her while she was working as a prostitute. She was convicted and sentenced to death for six of the murders, and executed via lethal injection on October 9, 2002.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aileen_Wuornos

check out her interview, look at her eyes, and she did pass the insanity test LOL

Kinda thinking the women have the men beat when it comes to wiping you off this green earth! lol,. Aileen Wuornos wasn't a stupid woman though. A few things she said were a little out there, but most of her words were the truth. There is such things as sonic frequencies, they use them in the movies to this very day. The frequencies adjust your moods throughout the whole movie! Music industry uses it as well. I know a bunch of cops, and even a female detective. They definitely know who the prostitutes are in town. And many of them can easily take advantage of the situation. I don't know .. I kinda have mixed reviews about her sentencing..[/quote]

bet ya didnt know she was a lez and totally hated men if i remember right her g/friend was involved with a couple of the killings....

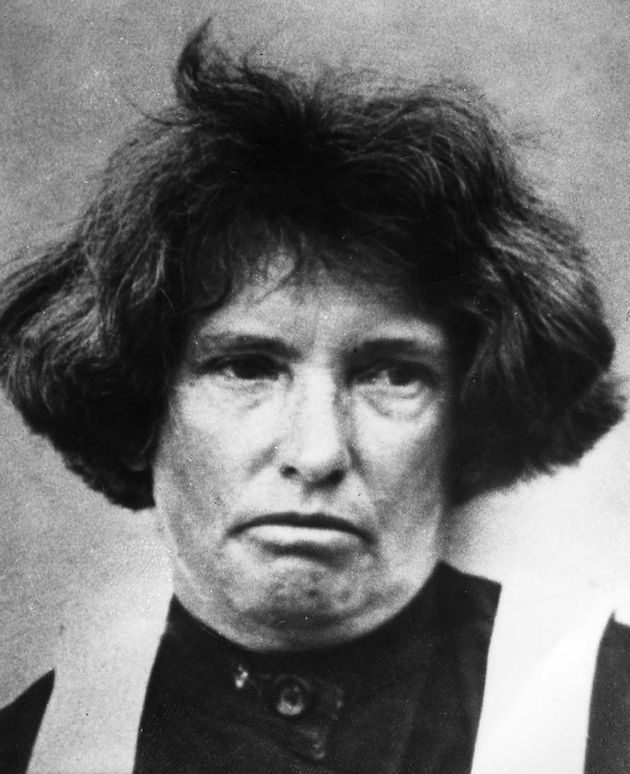

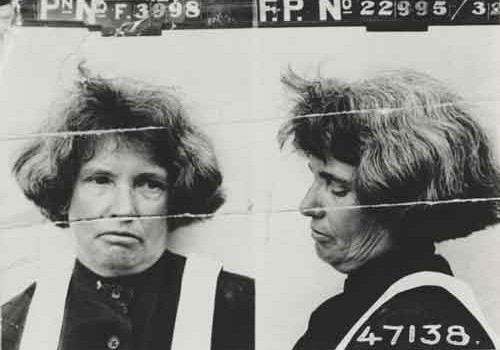

Minnie Dean

Williamina "Minnie" Dean (2 September 1844 – 12 August 1895) was a New Zealander who was found guilty of infanticide and hanged. She was the only woman to receive thedeath penalty in New Zealand.

Minnie Dean (also known as The Southland Witch) was born in Greenock, in western Scotland. Her father, John McCulloch, was a railway engineer. Her mother, Elizabeth Swan, died of cancer in 1857. It is unknown when she arrived in New Zealand, but by the early 1860s, she was living in Invercargill with two young children. She claimed she was the widow of a Tasmanian doctor, although no evidence of a marriage has been found. She was still using her birth name, McCulloch.

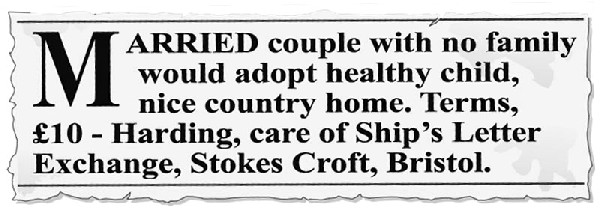

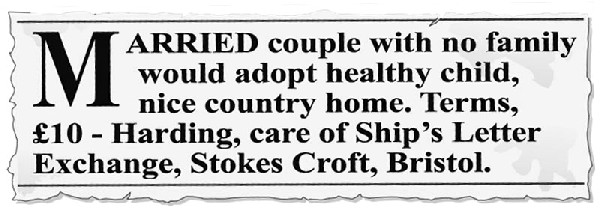

In 1872, she married an inkeeper named Charles Dean. The two lived in Etal Creek, then an important stop on the route from Riverton to the Otago goldfields. When the goldrush died down, the couple turned to farming, but were soon in dire financial straits. The family moved to Winton, where Charles Dean took up pig farming. Minnie Dean, meanwhile, began to earn money by taking in unwanted children in exchange for payment. In an era when there were few methods of contraception, and when childbirth outside marriage was frowned upon, there were many women wishing to discreetly send their children away for adoption — as such, Minnie Dean was not short on customers. It is believed that she was responsible for as many as nine young children at any one time. She received payment either weekly or in a lump sum.

Infant mortality was a significant problem in New Zealand at this time (as it was estimated to run to about eighty to one hundred infants out of one thousand colonial births).[1] As such, a number of children under Dean's care died of various illnesses. In March 1889, a six-month old child had died of convulsions, while in October 1891, a six-week old baby had perished from cardiovascular and respiratory ailments, while a boy allegedly drowned under her care during 1894. She hid the body in her garden, arousing further suspicions. A coroner's inquest was held, and Dean was not held responsible for the deaths, due to universally poor standards of hygiene, even at childbirth itself. Nevertheless, Dean came to be distrusted by the community, and rumours of mistreatment circulated. Additionally, children under Dean's care allegedly went missing without explanation. In the public's mind, this linked Dean to cases of infanticide or baby farming in the United Kingdom and Australia, where women killed children under their care to avoid having to support them. At the time, lax childcare legislation meant that Dean did not have to keep records of the children she agreed to take in, and so proving that the children had disappeared was difficult.

Before Dean's trial and execution, three other women had been tried and sentenced to death- Caroline Whitting (1872), Phoebe Veitch(1883: d.1891) and Sarah-Jane and Anna Flannagan (1891). In each case, those sentences were commuted to life imprisonment. In each case, child murder was the culpable offence. Thirty years later, in 1926, Daniel Cooper was also convicted of baby farming and also executed for the offence, although Martha, his second wife was acquitted.

In 1895, Dean was observed boarding a train carrying a young baby and a hatbox, but observed leaving the same train without the baby and only the hatbox. As railway porters later testified, the object was suspiciously heavy. A woman, Jane Hornsby, came forward claiming to have given her granddaughter, Eva, to Dean, and clothes identified as belonging to this child were found at Dean's residence, but Dean could not produce the child herself. A search along the railway line found no sign of the child. Dean was arrested and charged with murder. Her garden was dug up, and three bodies (two of babies, and one of a boy estimated to be three years old) were uncovered. An inquest found that one child (Eva) had died of suffocation and one, later identified as one year-old Dorothy Edith Carter, had died from an overdose of laudanum (used on children to sedate them). The cause of death for the third child was not determined. Dean was charged with their murder.

Hatboxes containing baby dolls, such as this one, were sold outside the courthouse during Minnie Dean's 1895 trial.

In her trial, Dean's lawyer Alfred Hanlon argued that all deaths were accidental, and that they had been covered up to prevent adverse publicity of the sort that Dean had previously been subjected to. On 21 June 1895, however, Dean was found guilty of Dorothy Carter's murder, and sentenced to death. Between June and August 1895, Dean wrote her own account of her life. Altogether, she claimed to have cared for twenty eight children. Of these, five were in good health when her establishment was raided, six had died whilst under her care, and one had been reclaimed by her parents. Apart from her two adopted daughters, that left fourteen or so children unaccounted for, according to her own record.

On 12 August, she was hanged by the official executioner Tom Long in Invercargill, at the intersection of Spey and Leven streets, in what is now the Noel Leeming carpark. She is the only woman to have been executed in New Zealand, and as capital punishment in New Zealand has been abolished, it is likely that she will retain that distinction. She is buried in Winton, alongside her husband, who died in a house fire in 1908. Her crimes led to the belated passage of child welfare legislation in New Zealand- the Infant Life Protection Act 1893 and the Infant Protection Act 1896.

In 1985, Dean's trial was the subject of In Defence of Minnie Dean, the first episode of the Emmy-nominated Hanlon New Zealand television drama series about the career of Dean's lawyer.[2][3] The episode won the Best Director, Best Drama Programme, Drama Script, and Performance, Female, in a Dramatic Role categories at the 1986 Listener Television Awards (also called the GOFTA Awards), and "contributed to a re-evaluation of Dean's conviction".[2][3][4]

Minnie Dean is referenced in Dudley Benson's 2006 song "It's Akaroa's Fault" ("I don't want to meet Minnie Dean at the end of my life/If I were to meet her I'd keep her hatbox in sight"). Authors Lynley Hood and John Rawle wrote posthumous accounts and reconstructions of the case as the centenary of her apprehension and execution occurred, in 1995.

On Friday 30 January 2009 the Otago Daily Times reported that a headstone had appeared mysteriously on Dean's grave. The headstone reads "Minnie Dean is part of Winton's history Where she now lies is now no mystery". It is unknown who placed the headstone there. Her family had been considering it but claim that this was not their doing.

The Southland Times reported on 23 February 2009 that the family laid a headstone to honour Dean and her husband's grave.

Williamina "Minnie" Dean

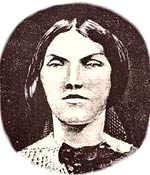

Minnie Dean at the time of her marriage in 1872

Born 2 September 1844Greenock, Scotland

Died 12 August 1895 (aged 50)

Invercargill, New Zealand

Cause Hanged

Resting place Winton Cemetery

Conviction(s) Murder (1895)

Penalty Death

Conviction Status Executed

Williamina "Minnie" Dean (2 September 1844 – 12 August 1895) was a New Zealander who was found guilty of infanticide and hanged. She was the only woman to receive thedeath penalty in New Zealand.

Contents

[hide]

- 1 Early life

- 2 Murder case and execution

- 3 In popular culture

- 4 See also

- 5 References

- 6 Bibliography

- 7 External links

[edit]

Early lifeMinnie Dean (also known as The Southland Witch) was born in Greenock, in western Scotland. Her father, John McCulloch, was a railway engineer. Her mother, Elizabeth Swan, died of cancer in 1857. It is unknown when she arrived in New Zealand, but by the early 1860s, she was living in Invercargill with two young children. She claimed she was the widow of a Tasmanian doctor, although no evidence of a marriage has been found. She was still using her birth name, McCulloch.

In 1872, she married an inkeeper named Charles Dean. The two lived in Etal Creek, then an important stop on the route from Riverton to the Otago goldfields. When the goldrush died down, the couple turned to farming, but were soon in dire financial straits. The family moved to Winton, where Charles Dean took up pig farming. Minnie Dean, meanwhile, began to earn money by taking in unwanted children in exchange for payment. In an era when there were few methods of contraception, and when childbirth outside marriage was frowned upon, there were many women wishing to discreetly send their children away for adoption — as such, Minnie Dean was not short on customers. It is believed that she was responsible for as many as nine young children at any one time. She received payment either weekly or in a lump sum.

Infant mortality was a significant problem in New Zealand at this time (as it was estimated to run to about eighty to one hundred infants out of one thousand colonial births).[1] As such, a number of children under Dean's care died of various illnesses. In March 1889, a six-month old child had died of convulsions, while in October 1891, a six-week old baby had perished from cardiovascular and respiratory ailments, while a boy allegedly drowned under her care during 1894. She hid the body in her garden, arousing further suspicions. A coroner's inquest was held, and Dean was not held responsible for the deaths, due to universally poor standards of hygiene, even at childbirth itself. Nevertheless, Dean came to be distrusted by the community, and rumours of mistreatment circulated. Additionally, children under Dean's care allegedly went missing without explanation. In the public's mind, this linked Dean to cases of infanticide or baby farming in the United Kingdom and Australia, where women killed children under their care to avoid having to support them. At the time, lax childcare legislation meant that Dean did not have to keep records of the children she agreed to take in, and so proving that the children had disappeared was difficult.

Before Dean's trial and execution, three other women had been tried and sentenced to death- Caroline Whitting (1872), Phoebe Veitch(1883: d.1891) and Sarah-Jane and Anna Flannagan (1891). In each case, those sentences were commuted to life imprisonment. In each case, child murder was the culpable offence. Thirty years later, in 1926, Daniel Cooper was also convicted of baby farming and also executed for the offence, although Martha, his second wife was acquitted.

[edit]

Murder case and executionIn 1895, Dean was observed boarding a train carrying a young baby and a hatbox, but observed leaving the same train without the baby and only the hatbox. As railway porters later testified, the object was suspiciously heavy. A woman, Jane Hornsby, came forward claiming to have given her granddaughter, Eva, to Dean, and clothes identified as belonging to this child were found at Dean's residence, but Dean could not produce the child herself. A search along the railway line found no sign of the child. Dean was arrested and charged with murder. Her garden was dug up, and three bodies (two of babies, and one of a boy estimated to be three years old) were uncovered. An inquest found that one child (Eva) had died of suffocation and one, later identified as one year-old Dorothy Edith Carter, had died from an overdose of laudanum (used on children to sedate them). The cause of death for the third child was not determined. Dean was charged with their murder.

Hatboxes containing baby dolls, such as this one, were sold outside the courthouse during Minnie Dean's 1895 trial.

In her trial, Dean's lawyer Alfred Hanlon argued that all deaths were accidental, and that they had been covered up to prevent adverse publicity of the sort that Dean had previously been subjected to. On 21 June 1895, however, Dean was found guilty of Dorothy Carter's murder, and sentenced to death. Between June and August 1895, Dean wrote her own account of her life. Altogether, she claimed to have cared for twenty eight children. Of these, five were in good health when her establishment was raided, six had died whilst under her care, and one had been reclaimed by her parents. Apart from her two adopted daughters, that left fourteen or so children unaccounted for, according to her own record.

On 12 August, she was hanged by the official executioner Tom Long in Invercargill, at the intersection of Spey and Leven streets, in what is now the Noel Leeming carpark. She is the only woman to have been executed in New Zealand, and as capital punishment in New Zealand has been abolished, it is likely that she will retain that distinction. She is buried in Winton, alongside her husband, who died in a house fire in 1908. Her crimes led to the belated passage of child welfare legislation in New Zealand- the Infant Life Protection Act 1893 and the Infant Protection Act 1896.

[edit]

In popular cultureIn 1985, Dean's trial was the subject of In Defence of Minnie Dean, the first episode of the Emmy-nominated Hanlon New Zealand television drama series about the career of Dean's lawyer.[2][3] The episode won the Best Director, Best Drama Programme, Drama Script, and Performance, Female, in a Dramatic Role categories at the 1986 Listener Television Awards (also called the GOFTA Awards), and "contributed to a re-evaluation of Dean's conviction".[2][3][4]

Minnie Dean is referenced in Dudley Benson's 2006 song "It's Akaroa's Fault" ("I don't want to meet Minnie Dean at the end of my life/If I were to meet her I'd keep her hatbox in sight"). Authors Lynley Hood and John Rawle wrote posthumous accounts and reconstructions of the case as the centenary of her apprehension and execution occurred, in 1995.

On Friday 30 January 2009 the Otago Daily Times reported that a headstone had appeared mysteriously on Dean's grave. The headstone reads "Minnie Dean is part of Winton's history Where she now lies is now no mystery". It is unknown who placed the headstone there. Her family had been considering it but claim that this was not their doing.

The Southland Times reported on 23 February 2009 that the family laid a headstone to honour Dean and her husband's grave.

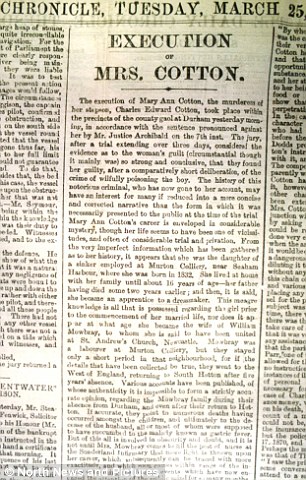

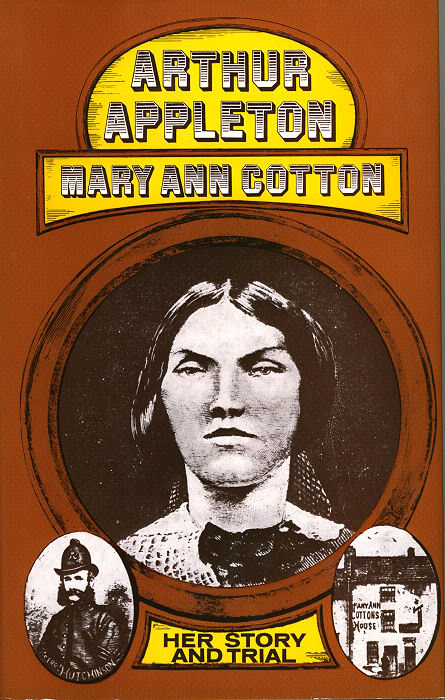

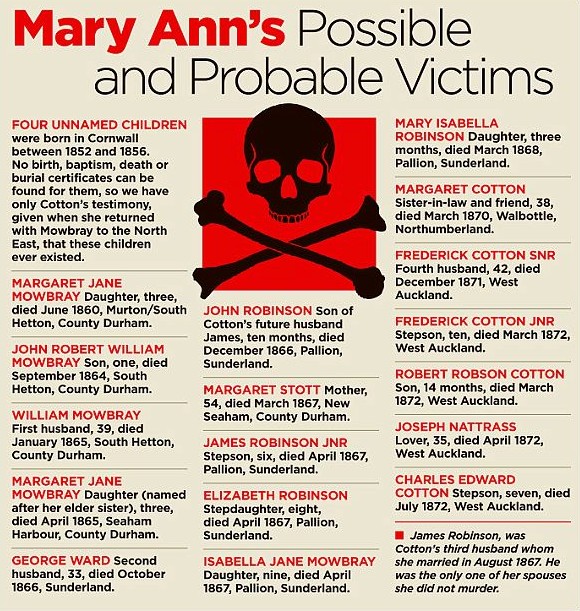

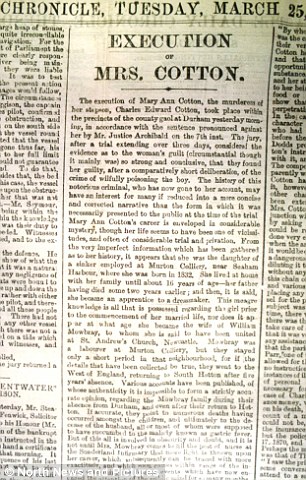

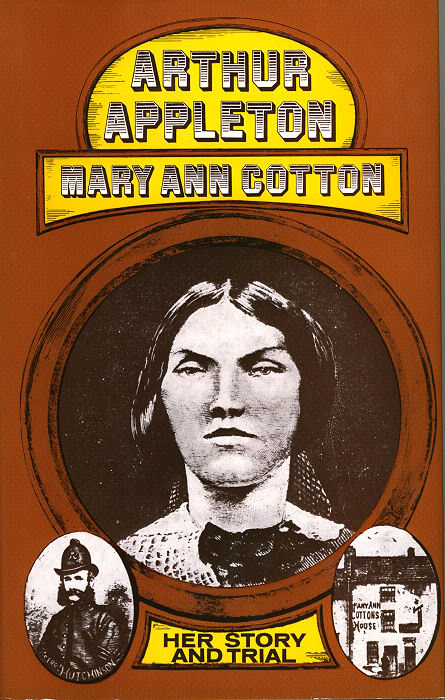

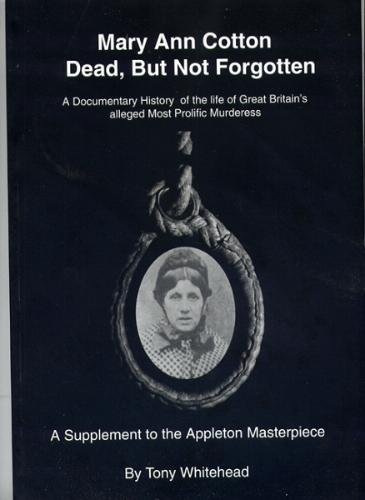

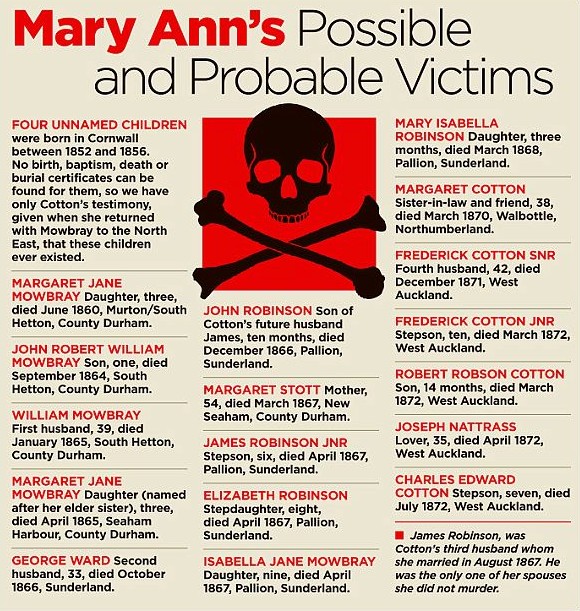

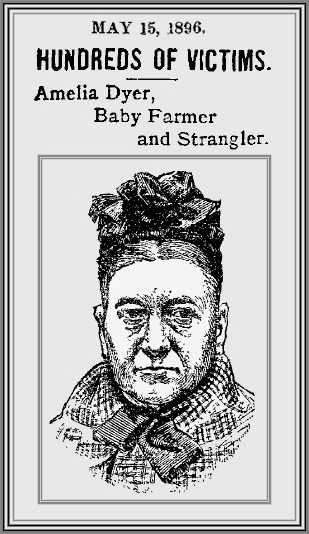

Mary Ann Cotton

Born Mary Ann Robson

Classification: Serial killer

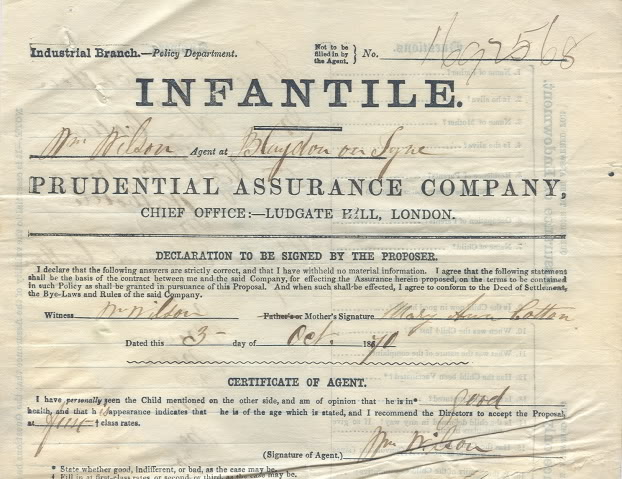

Characteristics: Poisoner - To collect insurance money

Number of victims: 1 - 21 +

Date of murder: 1857 - 1872

Date of arrest: 1973

Date of birth: October 1, 1832

Victims profile: Eight of her own children, seven stepchildren, her mother, three husbands, a lover – and an inconvenient friend

Method of murder: Poisoning (arsenic)

Location: North East England, England, United Kingdom

Status: Executed by hanging in Durham prison on March 24, 1873

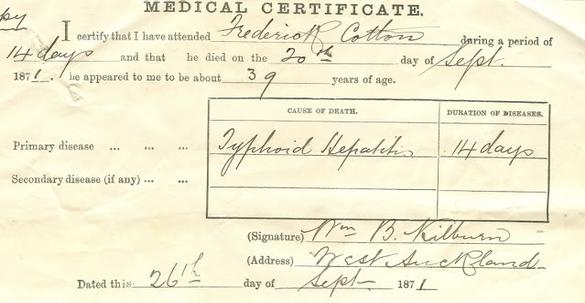

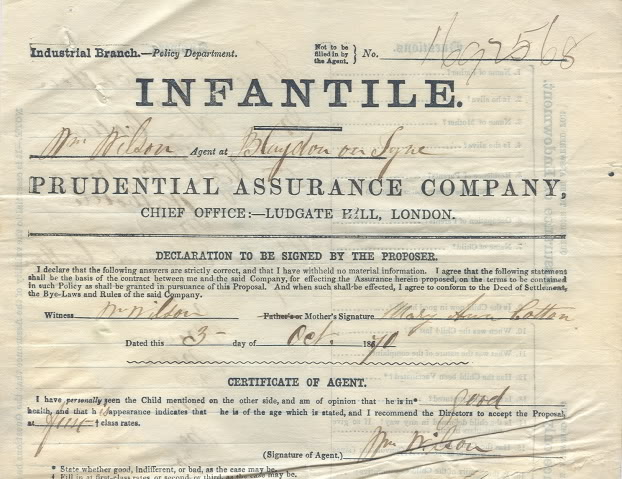

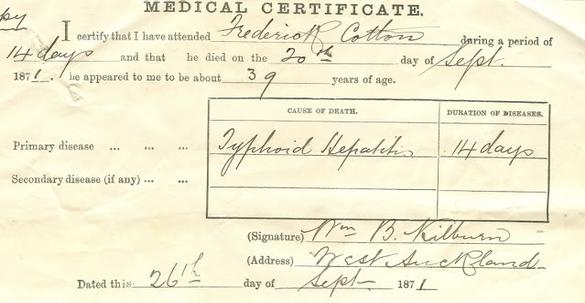

In 1871, 40-year-old Mary Ann Cotton and her husband, 39-year-old Frederick moved into a home in County Durham, with his two stepsons and her 7-month-old baby. Two months later Frederick died of gastric fever and one of Mary's lovers, Joseph Natrass moved in.

In the space of a month Belle's baby, Natrass and Frederick's son all died in the house. On the 12 July 1872 the other son of Frederick died, all the deaths caused suspicion and a neighbour went to the police.

A post mortem was carried out on the stepson and it revealed him to be poisoned with arsenic. The bodies of the other dead were exhumed and they showed that arsenic was the cause of death. Mary was arrested and charged with the murder of her stepson. She went to trial in March 1873, claiming that they were accidentally killed by arsenic contained in wallpaper, but the prosecution had evidence that she had purchased arsenic. Mary Ann Cotton was found guilty and sentenced to death.

Cotton was suspected of the murders of 14 people, in her older life twenty one people close to her died. Her motive was gain, as she would marry, kill and collect the insurance money, then repeat it again. She was hanged in Durham prison on March 24, 1873.

Mary Ann Cotton (1832 – 1873) was a British serial killer in the 19th century. Employing poison, she is suspected of murdering up to twenty-one people. She was the most prolific British serial killer before Harold Shipman.

She was born Mary Ann Robson in 1832 in the village of Low Moorsley in Tyne and Wear, Northern England. Her father was a miner who died when she was eight, and Mary and her brother were raised by their mother, who was impoverished after the loss of her husband. Mary's mother later remarried, and Mary is said to have loathed her stepfather.

Conflict with her stepfather led her to flee the family home when she was 16. She married in 1852, aged 20, and had five children, four of whom died in infancy, a high rate of infant mortality even in the Victorian era. Mary frequently argued with her husband, who died suddenly in January 1865.

Now widowed, Mary returned to Sunderland and a few months later got married again, her new husband dying in October 1865 from an unexplained illness.

In 1866, Mary's mother died after a sudden illness. At the time Mary was enjoying a relationship with a widower, James Robinson, whom she soon married. Robinson had four children by his late wife, although two suddenly died soon after he met Mary. Robinson became suspicious of his new wife, especially when she kept pestering him to take out life insurance. In late 1869, having borne him a daughter, Mary walked out on Robinson, who was the only husband to survive a marriage to her.

In 1870 Mary married another widower, Frederick Cotton, whose surname she took and by which name she is usually known, even though the marriage was effectively null and void because Mary had not legally divorced her previous husband.

Mary Cotton had a son with Frederick Cotton. Soon, Frederick's sister, two sons from his previous marriage and a number of friends died after sudden illnesses. Frederick himself died in December 1871, soon followed by the baby Mary had by him. Mary quickly remarried, but her new husband quickly died after a short illness.

In the spring of 1872, one of Mary Cotton's few surviving stepchildren, Charles Cotton, whose father had been Frederick Cotton, died suddenly. Word quickly spread around the neighbourhood concerning the way so many of Mary's nearest and dearest had died so suddenly over the previous two decades.

Thomas Riley, a minor government official, was suspicious of the latest death. Mary Cotton had told him that Charles had been "in the way" of her plans of getting remarried. Furthermore, young Charles had appeared very healthy up until his sudden death, which was supposedly due to gastric fever. Mary tried to collect on the life insurance she had taken out on Charles Cotton's life, but the insurance company refused to pay until the body of the deceased had been investigated more thoroughly. Charles Cotton's remains were exhumed and a significant trace of arsenic was found in the deceased's stomach.

Charges soon followed and Mary Cotton was eventually tried for the murder of Charles Cotton, her final victim. She was convicted and sentenced to death.

On March 24, 1873, Mary Cotton was hanged. The execution was botched with Mary failing to die from the initial drop after the gallow's trapdoor opened. Instead, she slowly choked to death as she dangled on the end of the noose.

In spite of the fact that she maintained her innocence to the end, her reputation as the first female serial killer in Britain stands, and her story is the subject of a children's rhyme:

Mary Ann Cotton – She's dead and she's rotten! She lies in her bed With her eyes wide open.

Sing, sing! "Oh, what can I sing? Mary Ann Cotton is tied up with string."

Where, where? "Up in the air – selling black puddings a penny a pair."

Reference

Look For the Woman by Jay Robert Nash. M. Evans and Company, Inc. 1981. ISBN 0871313367

Mary Ann Cotton (born Mary Ann Robson in October 1832 in Low Moorsley, County Durham – died 24 March 1873) was an English woman convicted of murdering her children and believed to have murdered up to 21 people, mainly by arsenic poisoning.

Early life

Mary Ann Robson was born in October 1832 at Low Moorsley (now part of Houghton-le-Spring in the City of Sunderland) and baptised at St Mary's, West Rainton on 11 November. Her father Michael, a miner, was ardently religious and a fierce disciplinarian.

When Mary Ann was eight, her parents moved the family to the County Durham village of Murton, where she went to a new school and found it difficult to make friends. Soon after the move her father fell 150 feet (46 m) to his death down a mine shaft at Murton Colliery.

In 1843, Mary Ann's widowed mother, Margaret (née Lonsdale) married George Stott, with whom Mary Ann did not get along. At the age of 16, she moved out to become a nurse at Edward Potter's home in the nearby village of South Hetton. After three years there, she returned to her mother's home and trained as a dressmaker.

Husband 1: William Mowbray

In 1852, at the age of 20, Mary Ann married colliery labourer William Mowbray in Newcastle Upon Tyne register office; they soon moved to Plymouth, Devon. The couple had five children, four of whom died from gastric fever. William and Mary Ann moved back to North East England where they had, and lost, three more children. William became a foreman at South Hetton Colliery and then a fireman aboard a steam vessel. He died of an intestinal disorder in January 1865. William's life was insured by the British and Prudential Insurance office and Mary Ann collected a payout of £35 on his death, equivalent to about half a year's wages for a manual labourer at the time.

Husband 2: George Ward

Soon after Mowbray's death, Mary Ann moved to Seaham Harbour, County Durham, where she struck up a relationship with Joseph Nattrass. He, however, was engaged to another woman and she left Seaham after Nattrass’s wedding. During this time, her 3½-year-old daughter died, leaving her with one child out of the nine she had borne. She returned to Sunderland and took up employment at the Sunderland Infirmary, House of Recovery for the Cure of Contagious Fever, Dispensary and Humane Society. She sent her remaining child, Isabella, to live with her mother.

One of her patients at the infirmary was an engineer, George Ward. They married in Monkwearmouth on 28 August 1865. He continued to suffer ill health; he died in October 1866 after a long illness characterised by paralysis and intestinal problems. The attending doctor later gave evidence that Ward had been very ill, yet he had been surprised that the man's death was so sudden. Once again, Mary Ann collected insurance money from her husband's death.

Husband 3: James Robinson

James Robinson was a shipwright at Pallion, Sunderland, whose wife, Hannah, had recently died. He hired Mary Ann as a housekeeper in November 1866. One month later, when James' baby died of gastric fever, he turned to his housekeeper for comfort and she became pregnant. Then Mary Ann's mother, living in Seaham Harbour, County Durham, became ill so she immediately went to her. Although her mother started getting better, she also began to complain of stomach pains. She died at age 54 in the spring of 1867, nine days after Mary Ann's arrival.

Mary Ann's daughter Isabella, from the marriage to William Mowbray, was brought back to the Robinson household and soon developed bad stomach pains and died; so did another two of Robinson's children. All three children were buried in the last two weeks of April 1867.

Robinson married Mary Ann at St Michael's, Bishopwearmouth on 11 August 1867. Their child, Mary Isabella, was born that November, but she became ill with stomach pains and died in March 1868.

Robinson, meanwhile, had become suspicious of his wife's insistence that he insure his life; he discovered that she had run up debts of £60 behind his back and had stolen more than £50 that she was supposed to have put in the bank. The last straw was when he found she had been forcing his children to pawn household valuables for her. He threw her out.

"Husband" 4: FrederickCotton

Mary Ann was desperate and living on the streets. Then her friend Margaret Cotton introduced her to her brother, Frederick, a pitman and recent widower living in Walbottle, Northumberland, who had lost two of his four children. Margaret had acted as substitute mother for the remaining children, Frederick Jr. and Charles. But in late March 1870 Margaret died from an undetermined stomach ailment, leaving Mary Ann to console the grieving Frederick Sr. Soon her eleventh pregnancy was underway.

Frederick and Mary Ann were bigamously married on 17 September 1870 at St Andrew's, Newcastle Upon Tyne and their son Robert was born early in 1871. Soon after, Mary Ann learnt that her former lover, Joseph Nattrass, was living in the nearby village of West Auckland, and no longer married. She rekindled the romance and persuaded her new family to move near him. Frederick followed his predecessors to the grave in December of that year, from “gastric fever." Insurance had been taken out on his life and the lives of his sons.

Two lovers

After Frederick's death, Nattrass soon became Mary Ann’s lodger. She gained employment as nurse to an excise officer recovering from smallpox, John Quick-Manning. Soon she became pregnant by him with her twelfth child.

Frederick Jr. died in March 1872 and the infant Robert soon after. Then Nattrass became ill with gastric fever, and died — just after revising his will in Mary Ann’s favour.

The insurance policy Mary Ann had taken out on Charles' life still awaited collection.

Death of Charles Edward Cotton and inquest

Mary Ann's downfall came when she was asked by a parish official, Thomas Riley, to help nurse a woman who was ill with smallpox. She complained that the last surviving Cotton boy, Charles Edward, was in the way and asked Riley if he could be committed to the workhouse. Riley, who also served as West Auckland's assistant coroner, said she would have to accompany him. She told Riley that the boy was sickly and added: “I won’t be troubled long. He’ll go like all the rest of the Cottons.”

Five days later, when Mary Ann told Riley that the boy had died. Riley went to the village police and convinced the doctor to delay writing a death certificate until the circumstances could be investigated.

Mary Ann’s first port of call after Charles' death was not the doctor’s but the insurance office. There, she discovered that no money would be paid out until a death certificate was issued. An inquest was held and the jury returned a verdict of natural causes. Mary Ann claimed to have used arrowroot to relieve his illness and said Riley had made accusations against her because she had rejected his advances.

Then the local newspapers latched on to the story and discovered Mary Ann had moved around northern England and lost three husbands, a lover, a friend, her mother, and a dozen children, all of whom had died of stomach fevers.

Arrest

Rumour turned to suspicion and forensic inquiry. The doctor who attended Charles had kept samples, and they tested positive for arsenic. He went to the police, who arrested Mary Ann and ordered the exhumation of Charles' body. She was charged with his murder, although the trial was delayed until after the delivery of her last child in Durham Gaol on 10 January 1873, whom she named Margaret Edith Quick-Manning Cotton.

Trial and execution

Mary Ann Cotton's trial began on 5 March 1873. The delay was caused by a problem in the selection of the public prosecutor. A Mr. Aspinwall was supposed to get the job, but the Attorney General, Sir John Duke Coleridge, chose his friend and protégé Charles Russell. Russell's appointment over Aspinwall led to a question in the House of Commons. However, it was accepted, and Russell conducted the prosecution. The Cotton case would be the first of several famous poisoning cases he would be involved in during his career, including those of Adelaide Bartlett and Florence Maybrick.

The defence in the case was handled by Mr. Thomas Campbell Foster. The defence at Mary Ann's trial claimed that Charles died from inhaling arsenic used as a dye in the green wallpaper of the Cotton home. The jury retired for 90 minutes before finding Mary Ann guilty.

The Times correspondent reported on 20 March: "After conviction the wretched woman exhibited strong emotion but this gave place in a few hours to her habitual cold, reserved demeanour and while she harbours a strong conviction that the royal clemency will be extended towards her, she staunchly asserts her innocence of the crime that she has been convicted of." Several petitions were presented to the Home Secretary, but to no avail. Mary Ann Cotton was hanged at Durham County Gaol on 24 March, 1873 by William Calcraft.

Nursery rhyme

Mary Ann Cotton also had her own nursery rhyme of the same title, sung after her hanging on March 24, 1873.

Lyrics:

Mary Ann Cotton,

Dead and forgotten

She lies in her bed,

With her eyes wide open

Sing, sing, oh, what can I sing,

Mary Ann Cotton is tied up with string

Where, where? Up in the air

Sellin' black puddens a penny a pair.

"Black puddens" refers to black pudding, a type of sausage made with pig's blood.

Wikipedia.org

COTTON, Mary Ann (England)

Mary Ann Cotton was no ordinary, spur-of-the-moment killer; her murderous instincts were alleged to have resulted in the deaths of fifteen, perhaps even twenty people, including four husbands and eight children, and she gained the evil reputation of being the greatest mass murderess of all time.

By the age of forty she had married three times. Her first husband, whom she had married in 1852, was a young miner named William Mowbray, by whom she had four children. All of them just happened to die young, reportedly from gastric fever. William Mowbray also succumbed to illness, experiencing severe sickness and diarrhoea, and died in agony.

Mary, now seemingly grief-stricken at the loss of her husband and children, drew solace from her friends and cash from the insurance company. Realising that hospital work as a nurse would be the source not only of supplies of the poison she needed, but also of meeting further vulnerable and susceptible victims, she joined the staff of Sunderland Infirmary where, among others, she tended a patient named George Ward. So devoted were her ministrations that when he recovered he proposed marriage, her subsequent promise ‘in sickness and in health’ only applying to half the phrase, for fourteen months later, in 1866, he too shuffled off this mortal coil, but not before he had endowed all his worldly goods to her.

Not long afterwards, still in her widow’s weeds, she met James Robinson, a widower with three children. They were married in May 1867, and by December of that year regrettable coincidences also overwhelmed that family. Not only did James’ two young sons and daughter, plus William Mowbray’s nineyear-old daughter fall victim to gastric fever, but a later baby born to Mary and James joined its stepbrothers and sisters in the local cemetery. James himself had cause to thank his guardian angel when Mary incensed him so much by selling some of his possessions that he ejected her from the house.

The fact that her husband was still alive did not deter Mary from starting an intimate liaison with her next prey, Frederick Cotton, a man who already had two young sons from a former marriage. When he proposed to her, she bigamously married him, and, being a prudent wife who had to take care of her future, she took out three insurance policies, just in case. The number of children in their family became three when she had a little boy by Frederick, called Robert, the number of policies thereby increasing accordingly.

Early in 1872 a James Nattrass attracted her attention. This complicated matters, Frederick Cotton immediately becoming surplus to requirements – but not for long. Almost without warning he fell seriously ill, but by the time a doctor had arrived he was past all medical aid. Frederick’s 10-year-old son was not long in following his father to the grave, and Mary’s child, Robert, never reached puberty.

James now became her lover, but affection wasn’t everything, and eventually Mary decided that £30, the sum for which he had been insured, was preferable to the man himself, and so another coffin received an occupant and another grave was dug.

Mary could have continued in this manner, unchecked and unsuspected, until her stock of arsenic, a poison little recognised or diagnosed at the time, ran out, but for some unaccountable reason, perhaps a rare, charitable thought, she spared the life of Charles Edward, the eight-year-old Cotton boy; instead she decided to hand him over to the workhouse. When told that such was not possible without the parents also being admitted, she retorted, ‘I could have married again but for the child. But there, he won’t live long, he’ll go the way of all the Cotton family.’

Nor did he. Dispensing with mercy, she dispensed arsenic instead, gastric fever again being diagnosed as the cause of death.

But news of the child’s demise reached the ears of the workhouse master and, remembering the woman’s ominous rejoinder, he notified the authorities of his suspicions. The child’s body was exhumed and the amount of arsenic found within the viscera was unmistakable. And when the corpses of her other victims were disinterred and their post-mortems produced similar results, the game was up.

In March 1873 Mary Ann Cotton was charged at Durham with one murder, that of the young Charles Edward; so overwhelming was the evidence in that particular case that one charge was considered sufficient, and so it proved. Throughout the trial the woman in the dock remained composed and utterly self-assured; having borne a charmed life so far, she probably saw no reason why it should not continue. She pleaded not guilty and coolly explained that the arsenic in her possession was used to kill bedbugs in the house, but when the judge pronounced her guilty and sentenced her to be hanged, she fainted in the dock and had to be carried down to the cells.

If she had thought that because she was pregnant – she had wasted no time in taking a new lover, a local customs officer, following James’ funeral – she would escape the gallows, she was sadly mistaken: there was, of course, no question of executing her while heavy with child, but once the child was born, the law would take its course. After giving birth in gaol, she was deprived of her baby and arrangements were made for her to be deprived of her life in five days’ time.

The night before her execution she was heard by her warders to pray for salvation, a prayer which included James Robinson, her third husband and the only one to escape her homicidal proclivities. The customs man might also have congratulated himself on his lucky escape!

Feminine fashion at that time dictated that women wore dresses with long sleeves, plus a veil and gloves, and Mary Ann Cotton’s apparel on her execution day reflected this, for her veil was the white cap William Calcraft slipped over her head – nor did he omit the matching accessory, a hempen necklace. None of the watching officials saw him hesitate as he prepared his victim, nor did he waste a moment in operating the bolt.

However, as usual, nearly three minutes elapsed before the twitching figure ceased rotating and finally hung deathly still.

Following removal from the scaffold, Mary’s body was taken back into the prison building where, in order to take a cast of her head to be studied by members of the West Hartlepool Phrenological Society, all her luxurious tresses were cut off close to her skull. It was later stated that, far from being kept as gruesome souvenirs, every severed strand of hair was deposited in the coffin with her body.

Such was the publicity surrounding the case that shock waves of disbelief and horror spread across the country when the prosecuting lawyer described the ghastly deaths of her other victims, and with the minimum of delay a wax model of her joined the macabre company already occupying Mme Tussaud’s Chamber of Horrors, the museum publishing an updated catalogue which endorsed her execution as expiation ‘for crimes

for which no punishment in history could atone. The child she rocked on her knee today was poisoned tomorrow. Most of her murders were committed for petty gains; and she killed off husbands and children with the unconcern of a farm-girl killing poultry’.

Murderous though eternally feminine, Mary Ann was determined to look her best even for William Calcraft. When the wardresses went to escort her from the condemned cell to the scaffold, they found her brushing her long black hair in front of the mirror. As they approached her she turned and said brightly, ‘Right – now I am ready!’

Amazing True Stories of Female Executions by Geoffrey Abbott

She poisoned 21 people including her own mother, children and husbands. So why has no-one heard of Britain's FIRST serial killer, Mary Ann Cotton?

By David Wilson, Professor of Criminology at Birmingham University

DailyMail.co.uk

February 5, 2012

I pull up outside a house in the Durham mining village of West Auckland to find an anonymous-looking place: a slim, three-storey family home distinguished from its neighbours only by its pretty, blue-grey paint.

There are no clues as to its gruesome past. Even its original house number has been changed, perhaps from fear that the evil that was perpetrated here could pass down through successive generations of residents.

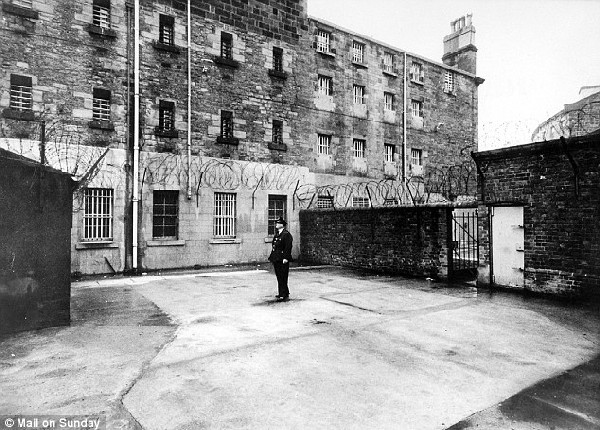

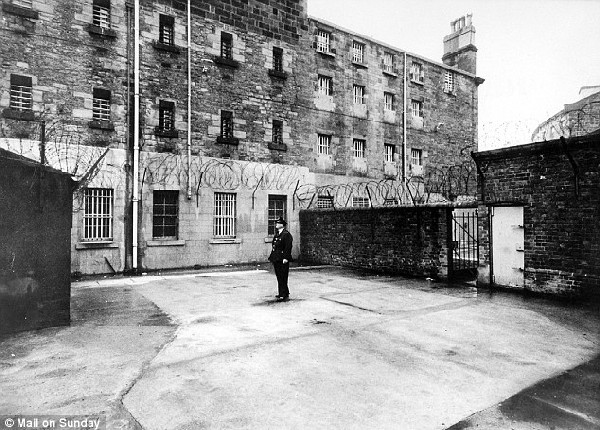

This is the home in which Britain’s first serial killer, Mary Ann Cotton, claimed her final victim. It is the house in which she was arrested and then taken away to be incarcerated, before eventually being executed at Durham Jail in March 1873.

Few have heard of the so-called ‘Black Widow’ killer who posed as a wife, widow, mother, friend and nurse to murder perhaps as many as 21 victims, living off her husbands before eventually claiming their estates. Two decades before Jack the Ripper would terrorise the streets of Whitechapel in London, Mary Ann Cotton had already become a killing machine, perhaps murdering as many as eight of her own children, seven stepchildren, her mother, three husbands, a lover – and an inconvenient friend.

Even crime aficionados, those familiar with such names as Shipman, Nilsen, Sutcliffe and West, know little or nothing of her. She has been largely erased from history and remains today only a half-remembered local curiosity even in her native North East.

There is certainly no walking tour retracing her murderous progress through County Durham, nor sad monuments erected to honour the memories of her victims. A woman who should have been a criminal icon has been reduced to little more than a chilling bedtime story and a Northern nursery rhyme: ‘Sing, sing, oh, what can I sing? Mary Ann Cotton is tied up with string. Where, where? Up in the air, sellin’ black puddens a penny a pair.’

A single book marked the centenary of her execution. As one of Britain’s leading criminologists and a former prison governor, I would like to know why. I have worked on police investigations and with many serial killers. Yet even to me, the life and terrible work of Mary Ann Cotton were largely a mystery.

And so throughout the spring and summer last year, I spent time in the North East researching a new book on this woman who travelled from one pit village to another leaving only gravestones behind her and who, in doing so, gained real, if loathsome, historical importance.

Here is not just the first British serial killer – someone who has killed more than three people in a period greater than 30 days – but the first to exploit and abuse the anonymity of a new industrial age.

My search began in the Home Office archives at Kew, South-West London, in the autumn of 2010. I found the usual records that measure the criminal careers of Victorian prisoners: her age, an occasional glimpse of what life had been like before prison, details of Mary Ann’s court appearances, and some letters from the governor of Durham Jail before her execution.

But these frustratingly formal scraps of biographical detail were hardly enough to explain what had caused Mary Ann to behave as she did, or to explain why she had all but disappeared.

There was, however, another valuable resource: scores of local newspapers and fragments of documents and artefacts in local archives and museums.

Victorian journalists had been adept at sketching in – and exaggerating – some of Mary Ann’s biographical background. There was also a crude ‘murderabilia’ market ensuring that some, at least, of Mary Ann’s correspondence had survived.

What is beyond dispute in an otherwise tangled search is that she was born Mary Ann Robson in 1832 at Low Moorsley, a small village near the town of Hetton-le-Hole. It would have been a hard upbringing. Her father Michael is recorded as a ‘pitman’, which meant that he worked in the local coal mines.

Soon after her arrival, they moved to East Rainton, and then to the pit village of Murton. This constant shifting from place to place was normal for the time and for the region.

Colliery contracts lasted no more than one year, and when their time was up, the miners and engineers went looking for more lucrative work. The mines drew in thousands of strangers from other parts of Britain, all eager to sell their labour, so adding to the sense of rootlessness.

Mary Ann’s father was killed in early 1842, when she was aged nine, apparently plummeting down a shaft while repairing a pulley wheel at the Murton Colliery. Mary Ann would have been instructed to find work and marry, which she did on July 18, 1852, becoming the wife of colliery worker William Mowbray.

First seeking their fortunes in Cornwall – another region where miners could find work – the Mowbrays returned to the North East in 1860, and this, so far as we know, is where the killing began. Her motives will always remain a matter of conjecture, but a strong pattern emerged: Mary Ann would find a man with an income, live with him until it became inconvenient, and then murder him. Numerous children – no one knows how many – were dispatched with the same callousness.

Her choice of poison was arsenic, favoured by murderers down the centuries for largely pragmatic reasons. First, it dissolves in a hot liquid, a cup of tea, for example, so is easy to administer. Second, it was readily available. Although by this stage, the authorities had started regulating the sale of arsenic, a high concentration could still be obtained in a substance known as ‘soft soap’, a household disinfectant.

There was a third reason, too: as Mary Ann well knew, the symptoms of arsenic poisoning were vomiting, diarrhoea and dehydration. A busy and unsuspecting doctor was always more likely to diagnose this cluster of symptoms as gastroenteritis – especially in patients who were poor and undernourished – than to suspect murder.

According to death and burial certificates, all her victims had died of gastric ailments.

It seems she also played the role of the grieving wife and mother to perfection, making it all the more difficult to be precise about the number of people she may have killed.

I’ve pieced together the trail of deaths associated with Mary Ann, and it starts with her first family. She bore William Mowbray, her first husband, at least four children, three of whom died young.

William died in January 1865, leaving Mary Ann to enjoy the £35 payout from British and Prudential Insurance, equivalent then to six months’ salary.

The total of murdered Mowbray children might have been greater still as, according to Mary Ann’s own testimony, she had earlier given birth to four children while the family was in the West Country. She used the insurance payout to move to Seaham Harbour, a port village in County Durham, so that she could be close to a lover called Joseph Nattrass.

Throughout her 20-year career of murder, wherever Nattrass went, she followed. He, too, would eventually become a victim. The insurance money also allowed her to embark on a career in nursing at Sunderland Infirmary – a deadly choice of occupation. There she met George Ward, an engineer who was a patient in the hospital, and who became her second husband in August 1865. He died little more than a year later in October 1866 leaving Mary Ann a second insurance payout.

Now a widow with just one living child from her marriage to Mowbray, Mary Ann was the perfect candidate for housekeeper to the newly widowed James Robinson, a shipwright at the Pallion yard on the River Wear in Sunderland. She took the job in November 1866 only for him to see his baby die a few weeks later.

Robinson turned to Mary Ann for comfort and yet again she became pregnant. But then her own mother fell sick. Mary Ann went to help – only for her mother to die nine days after Mary Ann returned home. Then Mary Ann’s daughter Isabella, who had been living with her grandmother, was brought back to the Robinson household at Pallion. She soon died too, as did two more of Robinson’s children, all three infants being buried in the last two weeks of April 1867.

Four months later, Robinson married Mary Ann, becoming her third husband. Their child, Mary Isabella, was born that November but died in March 1868. Robinson himself had a lucky escape. He was intrigued as to why she had wanted his life insured for a significant sum. He discovered that she had a secret debt of £60; that she’d stolen more than £50 that she should have banked on his behalf; and that she had forced his older children to pawn household valuables for her. He threw her out.

Mary Ann was desperate and, as newspaper reporters later suggested, was reduced to living on the streets. But yet again she found a man: her friend Margaret Cotton introduced her to her brother Frederick, a pitman and recent widower living in Walbottle, Northumberland.

Margaret was looking after Frederick and his two children, but she died from an undetermined stomach ailment in March 1870, leaving the coast clear for Mary Ann.

She and Frederick married bigamously in September and a son Robert was born in 1871. Frederick Cotton died in December of that year. Insurance, needless to say, had been taken out on his life and those of his sons.

Now Joseph Nattrass, her long-term lover, moved in as her lodger. However, she also found work as a nurse to an excise officer called John Quick-Manning, who was recovering from smallpox. As was her habit, she swiftly became pregnant by him (their daughter Margaret was born in prison while Mary Ann awaited execution) but, of course, she was still encumbered by her children from her third marriage. One of her stepsons died in March 1872 and her own son Robert soon after. Shortly after revising his will in her favour, Nattrass became sick and died in April.

The incompetence and heavy workload of local physicians, the poor nutrition of the urban working class, and imperfect record-keeping all helped the killings to go unchallenged. Meanwhile, Mary Ann’s experience as a nurse gave her perfect access – and she undoubtedly relished monitoring the painful, protracted deaths of her victims.

The court documents from her murder trial suggest an element of real sadism at work. Mary Ann’s neighbour Jane Hedley was one of those who witnessed the excruciating death of Nattrass.

Under oath, she told Durham Crown Court: ‘I was very friendly with the Prisoner. I assisted . . . during the time of the illness. I saw him have fits, he was very twisted up and seemed in great agony. He twisted his toes and his hands and worked them all ways. He drew his legs quite up.’

She describes how he ‘threw himself about’ and how his murderess – presumably in the guise of caring for him – was obliged to restrain him with force. It is clear from Jane Hedley’s account that, by this stage at least, Mary Ann had the confidence to kill right under the noses of the doctors.

It is hard not to believe that there was some element of enjoyment at the control she exercised – that she was, in other words, a psychopath. I believe she would have enjoyed holding down Nattrass as he died writhing in agony.

There is no doubt, too, that greed was a powerful motive as, husband by husband, she climbed the social ladder of a newly mobile society (in which, for the first time, ordinary people had life insurance).

In a previous, agricultural era, Mary Ann Cotton’s activities would have been watched, reported upon and controlled by her neighbours and their informal surveillance.

Only in the age of water power and steam were people free to leave their agricultural past behind them and shift restlessly from one settlement to another. In so doing, they could become whoever and whatever they wanted to be – even a serial killer.

If modern life had allowed her to become the ‘monster in human shape’ later described by the Newcastle Chronicle, it also provided the means of her eventual detection. She had poisoned her seven-year-old stepson Charles Edward Cotton in the summer of 1872, apparently to clear the way for yet another new relationship, this time with Quick-Manning. Following a hasty post-mortem conducted on a kitchen table, the inquest returned a verdict of death by natural causes.

But this was not enough for the police, the newspapers and the new discipline of forensic science, all of which played a part in uncovering her past. It was journalists, thriving on local gossip, who first prompted the investigations, soon exposing the tally of dead husbands, lost children, and the tell-tale signs of arsenic poisoning. And the police – still a comparatively new force in provincial life – were moved to act.

In 1873, Mary Ann Cotton was arrested, tried and hanged for the murder of the seven-year-old Charles Edward Cotton. Some of the child’s remains were exhumed from the garden of Dr Kilburn, the local GP, who had presumably buried them there because he harboured doubts about the death. Samples were taken and, using methods that were for the time revolutionary, the presence of arsenic was detected by Dr Thomas Scattergood at Leeds School of Medicine.

Mary Ann’s trial at Durham Crown Court lasted three days, and after being found guilty she was executed in Durham Jail on March 24, 1873, by hangman William Calcraft. Even the way she met her end proved sensational.

From her prison cell, Mary Ann wrote letter after letter to newspapers protesting her innocence. Further sympathy was generated when she gave birth in prison to the child of Quick-Manning and when the baby girl was taken from her before the execution.

Then the hanging itself was horribly botched. The drop below the trap door was too short. Mary Ann was left jerking on the end of the rope and Calcraft was obliged to press down upon her to finish the job.

Her desperate self-promotion and the terrible manner of her execution ensured a strangely sympathetic hearing in her final months and the immediate aftermath, and this has helped confuse our understanding of a woman who by any standards was a quite relentless killer. Had she not been arrested, I am confident there would have been many more victims.

What little historical analysis she has received has often been quite naive, citing her as an example of the hardships endured by women, or even suggesting that she had been the victim of a miscarriage of justice.

Perhaps this is why, today, some in the North East think of her only as ‘a kindly old lady’ from some dim and distant past. Geography and the methods that she chose to kill have contributed, too. Her crimes were not committed in one of the great cities, nor was she the kind of killer who left ripped or broken bodies on the street.

My search for her ended at Durham Prison, its flags flying in the wind and its new modern mission statement proudly on display. I asked to be shown the original gate through which Mary Ann would have entered prior to her appointment with the hangman so I could contemplate what, precisely, Mary Ann means in the modern world.

A prison officer told me that no one ever escapes from Durham Prison.

Not even Mary Ann, who remains – despite the odd bit of local lore in the villages of County Durham – long dead and buried in the prison’s grounds.

Murder Grew With Her: On The Trail Of Mary Ann Cotton, Britain’s First Serial Killer, by Professor David Wilson, will be published later this year.

Mary Ann Cotton

by Douglas MacGowan

Gastric Fever

Young Charles Cotton was dead. The doctor couldn't deny that. His stepmother, Mary Ann Cotton, claimed the seven-year-old boy had died from gastric fever, but the neighbors had noticed that a few too many in the Cotton household had died by similar stomach ailments in recent months, and gossip and suspicion ran rampant through the West Auckland neighborhood in County Durham, England. Slowly, investigators and gossips began looking into the background of 40-year-old Mary Ann.

The deeper they dug, the more Mary Ann's life looked like something out of a gothic horror novel: a childhood of near-abuse and near-poverty, an early marriage to flee an unkind stepfather, and a long string of family members who had succumbed to the mysterious “gastric fever” or other curious circumstances while Mary Ann was ominously close by.

Born in the small English village of Low Moorsley in October of 1832, Mary Ann Robson did not have a happy childhood, but neither did most children born in lower-class England in the early 19th century. Her parents were both younger than 20 when they married, and her father barely managed to keep his family fed by working as a miner in nearby East Rainton. Many who knew her spoke of her prettiness as a child and claimed that her beauty as a woman easily attracted many men who crossed her path. This is undoubtedly true, although a photograph taken of her after her incarceration shows a dowdy and somewhat plain figure.

Mary Ann's father was ardently religious, a fierce disciplinarian of Mary Ann and her younger brother Robert, and active in the local Methodist church’s choir and activities. No doubt his daughter feared him and his punishments. When Mary Ann was eight, her parents moved the family to the town of Murton, and her father continued working in the mines until one day about a year after their move when he fell down a mine shaft to an early death.

As Dickens would chronicle repeatedly in his classic writings, life for a lower-class family (especially one headed by a newly widowed woman) was extremely harsh in 19th century England. The specter of being sent to a workhouse, or being separated from her mother and brother, cast dark shadows over Mary Ann’s girlhood and was the cause of many nightmares.

Mary Ann never went into the workhouse, however, because her mother remarried. Her new stepfather did not like Mary Ann, and the feeling was mutual. Mary Ann began looking for an escape from her childhood home, although she owed one thing to her stepfather: his salary had kept her and her family from becoming homeless and destitute. Mary Ann learned at an early age that to avoid the miserable fate of her nightmares, she had to keep a steady flow of money coming her way – no matter what the method.

Mrs. Mowbray

Perhaps partly to escape the daily life with her stepfather, Mary Ann left home at the age of 16 to work as a servant in a prosperous household in South Hetton. The quality of Mary Ann’s work caused no complaint, although she began what would become a life riddled with sexual scandals. Soon after Mary Ann began working in the household, the South Hetton gossips were busy spreading tales about illicit meetings between Mary Ann and a local churchman.

After three years of service in South Hetton, Mary Ann left to train as a dressmaker and to marry a miner named William Mowbray, by whom she had become pregnant. After their wedding in July of 1852, the newlyweds moved around England as William got work at various mining sites and on railroad construction projects throughout England.

In the first four years of their marriage, William and Mary Ann had five children, although four of them died in infancy or soon after. Even though child mortality rates were high at the time, this was a bit extreme. However, Mary Ann and William were probably viewed as particularly unlucky parents suffering from grievous personal losses.

Mary Ann and William did not have a happy marriage. They argued frequently about money, as Mary Ann was still obsessed about never becoming poor. The quarrels grew so heated that William, in an apparent attempt to get some peace, landed a job on the steamer Newburn out of Sunderland, and was often away from home. Mary Ann and the surviving children followed him and took up residence in Sunderland, and the number of her children lost to indefinable illnesses continued at an alarming rate.

In January of 1865, William returned to the house to nurse an injured foot, and Mary Ann helped him with his recovery. Later that month, despite a doctor’s care, William died from a sudden intestinal disorder, which he had not shown evidence of before benefiting from Mary Ann’s care. Soon after William’s death, the doctor went to the Mowbray house to console the grieving widow but was surprised to find Mary Ann dancing about the room in a new dress she had bought with the money from William's life insurance.

Mrs. Ward

Soon after William Mowbray's death, Mary Ann moved her remaining children to Seaham Harbour, where she struck up a relationship with Joseph Nattrass, a local man who was engaged to another woman. Apparently unable to break up the engagement, Mary Ann left Seaham Harbour after Nattrass’s wedding (and after burying her 3 ½ year old daughter, leaving her with one living child out of the nine she had given birth to). Nattrass would reappear in Mary Ann's life several years later.

Mary Ann decided to return to Sunderland and found employment at The Sunderland Infirmary, House of Recovery for the Cure of Contagious Fever, Dispensary and Humane Society. Her remaining child, Isabella, was sent to live with her maternal grandmother, and would remain in her grandmother's care for more than two years.

At the Sunderland Infirmary, Mary Ann kept the wards clean with a mixture of soap and arsenic, and the Infirmary staff admired her diligence and friendliness with the patients. She chatted with many of them, but one in particular, engineer George Ward, took a fancy to Mary Ann. Soon after he was discharged from the Infirmary, he and Mary Ann were married at a church in Monkwearmouth in August of 1865. Although now settled into a new marriage and a steady household, Mary Ann did not fetch Isabella from her mother’s house.

Despite having been released from the Infirmary, George Ward developed health problems soon after marrying Mary Ann – and despite various treatments by his doctors, he died in October of 1866 after a long bout of paralysis in his limbs and chronic stomach problems. The doctor attending George was accused of incorrectly treating his patient, a point of view that Mary Ann actively encouraged, probably hoping to redirect any doubts away from herself.

Much later, at Mary Ann’s trial, people would wonder why nobody became suspicious of this woman who left a trail of husbands and children dead from startlingly similar illnesses over a very short time. But as Mary Ann had different doctors attend to her dying family and she relocated frequently, suspicions never built in a single community.

According to her pattern, after George Ward’s death in Sunderland, Mary Ann needed to move on.

Mrs. Robinson

Pallion shipwright James Robinson needed a housekeeper to care for his house and children after the death of his wife, Hannah. In November of 1866, Mary Ann applied for the position and was hired. Two days before Christmas, the baby of the family was interred after having developed, perhaps not surprisingly, gastric fever. Overcome with the grief of the recent deaths of his wife and then of his infant son, James turned to Mary Ann for solace and support. She provided comfort and apparently then some, as she was soon pregnant with Robinson's child.

A new marriage seemed in the forecast, but Mary Ann was diverted in March of 1867 by a sudden illness of her mother. Mary Ann returned to her mother’s home to help nurse the elderly lady back to health. As always, one of Mary Ann’s first tasks was to clean the house from top to bottom with soap and (her favorite cleaning additive) arsenic, of which she usually had an ample supply.

By the time Mary Ann arrived, however, her mother was doing much better, but Mary Ann decided to stay and look after her anyway – and to visit her own daughter Isabella, who was still living with her grandmother. Soon after being in Mary Ann’s care, her mother began complaining of stomach pains and died only nine days after Mary Ann’s arrival.

Returning to the Robinson household with her mother, young Isabella (who had enjoyed a life of good health while living away from Mary Ann) soon developed an incapacitating stomach ailment, as did two of Robinson’s children, and all three were buried within two weeks of each other at the end of April.

James Robinson must have grieved further over the loss of two more of his children, but apparently did not suspect any wrongdoing on Mary Ann’s part. He put his mourning aside in time for his wedding to Mary Ann in early August (at which Mary Ann stated her surname as "Mowbray" -- apparently her 14-month marriage to George Ward had slipped her mind). The couple's first child, Mary Isabella, was born in late November but had succumbed to illness by the first of March of 1868.

James now began to become suspicious of his new wife, not only by the frequency of deaths in the household since Mary Ann's arrival, but also by her constant requests for money and her pressing desire for him to insure his life.

Always punctual in his household finances, James was surprised when he received letters from his building society and his brother-in-law detailing debts Mary Ann had run up without his knowledge. He questioned his remaining children and found that they had been coerced by their new stepmother to pawn valuables from the house and give her the money. Irate, he threw Mary Ann out of the house, and she left – taking their young daughter with her.

In late 1869, after wandering the streets in the kind of life that Mary Ann had anxiously feared, Mary Ann and her daughter visited an acquaintance. During the course of the visit, Mary Ann asked her friend to watch the girl while she went out to mail a letter. Mary Ann never came back and the daughter was returned to James on the first day of 1870.

Mrs. Cotton

After weeks of desperate living, the year 1870 began well for Mary Ann. Her friend Margaret Cotton introduced her to her brother Frederick. Like James Robinson, Frederick was a recent widower and had lost two of his four children to early deaths. His sons Frederick Jr. and Charles were all that was left of his family. His sister acted as mother substitute for the family, although in late March she died from an undetermined stomach ailment – which left the opportunity wide open for Mary Ann to console the grieving Frederick and, in an echo of her relationship with James Robinson, she was soon pregnant with Frederick's child.

The couple were married in September of 1870, Mary Ann again signing the register as “Mary Ann Mowbray,” ignoring the fact that her surname was legally Robinson and that she was not divorced from James, who was very much alive. Mary Ann added bigamy to her growing list of crimes.

Mary Ann quickly set up housekeeping in Cotton’s house and just as quickly insured the lives of Frederick Cotton and his two sons.

After giving birth to a son, Robert, in early 1871, Mary Ann learned that her former paramour Joseph Nattrass was not married and was living in nearby West Aukland. Under some pretense Mary Ann moved the family there, and she quickly rekindled the relationship with Nattrass and became less interested in Frederick Cotton.

In December of 1871, Frederick died of gastric fever and Joseph Nattrass soon became a lodger in the three-time widow Mary Ann’s house. To keep her fears at bay and to keep money coming in, Mary Ann worked as a nurse to John Quick-Manning, an excise officer recovering from smallpox. Mary Ann apparently saw Quick-Manning as a better match than Nattrass, and soon became pregnant by him.

A marriage to Quick-Manning was hindered by the presence of the remaining Cotton household, so Mary Ann apparently went to work quickly and Frederick Jr. died in March of 1872 and the infant Robert soon after. Upon the death of her infant, Mary Ann stated that she did not want to bury the baby immediately, because Joseph Nattrass had also become ill with gastric fever, and she would wait and handle both burials at once. Nattrass obligingly passed away soon after Robert, but not before revising his will to leave everything to Mary Ann.

Only one of her husbands, James Robinson, had escaped a relationship with Mary Ann with his life. Other husbands, children, and most stepchildren had succumbed to gastric fever or stomach ailments – except for young Charles Cotton and Robinson’s children. The Robinson children were safely away from Mary Ann’s motherly care, but the insurance policy Mary Ann had taken out on Charles's life still waited to be collected.

The Trial of the Green Wallpaper

In late spring of 1872, Mary Ann sent Charles to a local chemist to purchase a small quantity of arsenic. The chemist refused to sell the poison to anyone under the age of 21, as was the law. Undeterred, Mary Ann asked a neighbor to purchase the substance and in July Charles died of gastric fever.

But Mary Ann had either been in the West Aukland area too long – or the neighbors were more readily skeptical – because suspicions were immediately aroused in neighbors and physicians.

The first person Mary Ann told about Charles’s death was Thomas Riley, a minor government official that she had consulted previously about the possibility of sending Charles into a workhouse. Riley had said that it would only be possible if she went with him, which she declined. She told Riley that the boy was “in the way” of a marriage with Quick-Manning, and predicted that, “I won’t be troubled long. He’ll go like all the rest of the Cotton family.” Riley said the boy appeared completely healthy, and so he was surprised when Mary Ann stopped him only five days later to say that young Charles had died.

Riley went to the village police office and to a doctor and outlined his growing suspicions. The doctor was similarly surprised to hear of the news, as he and his assistant had tended to Charles five times during the previous week and had detected nothing dire, let alone life threatening, in the young boy. Riley convinced the doctor to delay writing a death certificate until he could look into the situation further.

Mary Ann, instead of going to fetch the doctor after the boy’s death, hurried to the insurance office to collect on Charles’s policy. She learned that they would not issue the money until they had a death certificate, so she returned home to get the document from the doctor. Instead of receiving the certificate, Mary Ann received the startling news that she would not be receiving a signed death certificate until after a formal inquest was held.

A brief inquest was held and initial evidence did not indicate death by unnatural causes. Angry at Riley for initiating the investigation, Mary Ann told him that he could be responsible for the costs of Charles’s burial.

The young boy’s internment would most likely not have been the end of the story, and Mary Ann would have gone on with her plan to marry Quick-Manning and probably continue obtaining insurance monies from other gastric fever victims – but the local newspapers latched onto the story. They reported on the inquest but also alluded to the neighborhood gossip that Mary Ann was an active poisoner. These reports fanned the fires of rumors and hearsay and the feeling toward Mary Ann within West Aukland became bitter and suspicious. Quick-Manning was appalled by this type of gossip about his intended, and was apparently distressed enough to sever all connections with Mary Ann.

Mary Ann began preparations to leave the area, although her friends warned her that it would look suspicious if she did. Unknown to her, however, suspicions were already building and were about to close in around her. A doctor from the inquiry had kept samples of Charles’s stomach so that he could test them later in his lab. He did so, and the samples tested positive for arsenic. The doctor went to the authorities, who arrested Mary Ann and ordered Charles’s body exhumed and fully tested. The body of Joseph Nattrass was also dug up (after six exhumations of other corpses – the elderly sexton of the church couldn’t remember exactly where Nattrass was buried) and tested positive for the presence of arsenic. There was debate and talk of further exhumations, but it was decided to proceed with the single murder charge of young Charles Cotton – although the trial was delayed until after the delivery of the daughter fathered by John Quick-Manning.

Her trial began in March of 1873. The prosecution brought forth numerous witnesses who testified about Mary Ann's purchases of arsenic, the long list of gastric fever victims in her past, and about her statements regarding Charles being an obstacle to her marrying Quick-Manning.

The defense claimed that Charles may have obtained the arsenic that killed him from inhaling loose airborne particles of arsenic that was used as a dye in the green wallpaper of the Cotton home. The judge dismissed this theory and the jury retired for only 90 minutes before finding Mary Ann guilty of the murder of Charles Cotton.

Mary Ann continued to proclaim her innocence and wrote numerous letters to her friends and supporters. A letter to her estranged husband, James Robinson, asked him to bring her child and two stepchildren to visit her in prison. She went on to beg Robinson “if you have one spark of kindness in you – get my life spared…you know yourself there has been…most dreadful lies told about me. I must tell you: you are the cause of all my trouble. If you had not (abandoned me). I was left to wander the streets with my baby in my arms…no place to lay my head.”

Robinson ignored her letter, so she wrote him again and asked him to visit her. Robinson sent his brother-in-law to the prison in his stead. Mary Ann was upset that Robinson did not come himself, but asked the man about the children and requested that a petition be circulated in her support. Petitions were eventually created and signed by Mary Ann’s former employers, ministers, and other supporters. As her execution date neared, she was cheered by a letter from the couple who had adopted the infant she and Quick-Manning had conceived. She replied to the letter, asking the couple to “kiss my babe for me.”